Libertarianism again fails natural right.

Presidents’ Day Lessons for America’s 250th Birthday

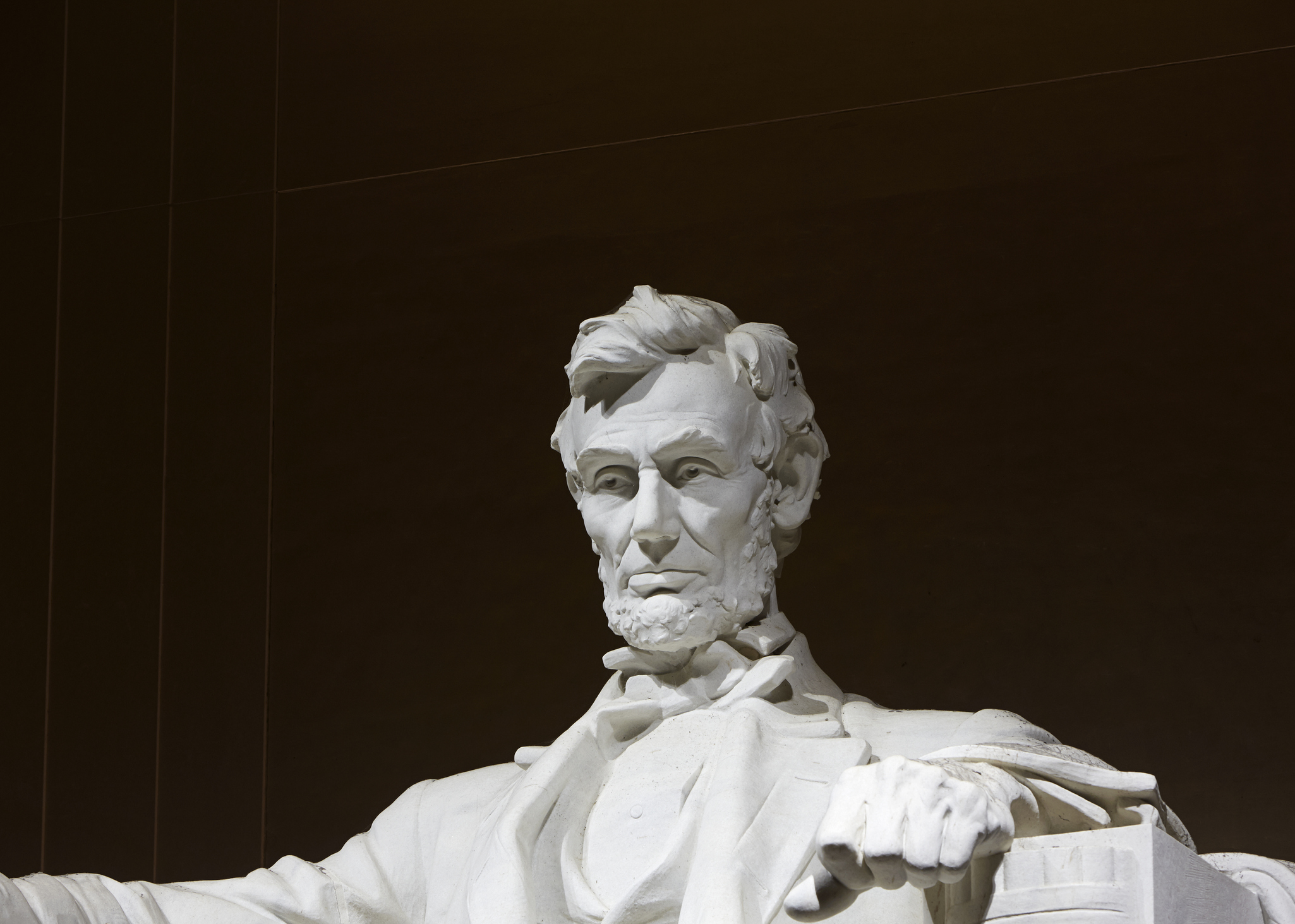

Washington and Lincoln displayed the best of the office.

Though Presidents’ Day is here, the nation as a whole does not seem to take much notice. That’s too bad, because we can learn some valuable lessons—both for our country and for ourselves as individuals—by taking time to reflect seriously on the character and actions of America’s presidents.

At first sight, it may seem paradoxical for a democratic nation to celebrate Presidents’ Day. In a democracy, after all, the people call the shots, and their elected leaders, even those of the highest rank, are just servants of the public. What is there to celebrate if the president is no more than an instrument of the people’s will? Why honor him more than any other public official? Why not have a holiday in honor of the sovereign people instead?

If we turn to the constitutional thought of our nation’s Founders, however, we find that these initial impressions do not capture their views of the presidency—nor of America’s democratic republic. The Federalist teaches us that we have a unitary executive, which makes the presidency unique among the political offices created by the Constitution. In the other branches of the federal government, the houses of Congress and the Supreme Court, power and responsibility rest with a majority of the members.

Only in the executive branch is authority vested—the executive power in its entirety—ultimately in one person at the top of the chain of command. Moreover, the matters entrusted to the chief executive, including foreign policy and national security, often involve the nation’s most important interests, which include the safety of its people. In sum, the person who occupies the presidency carries a greater weight of responsibility than anybody else in American public life. That fact alone is reason enough to dedicate one day of the year to having gratitude for those who have undertaken this mighty task.

Besides, as Alexander Hamilton reminds us in The Federalist’s account of the presidency, the president’s job is not merely to execute the will of the sovereign people. The Founders reasoned that since the people are not always correct about what the common good entails, the president should exercise and act on his own political judgments at times, perhaps even when they run counter to what the people want.

Indeed, Hamilton judged that the office of the presidency would sometimes demand of its occupant the classical virtue of magnanimity, or greatness of soul. This means the president should have both the mind and character necessary to rise above the people and serve them, even when they come under the influence of a strong passion that is damaging to the country and to their own well-being.

According to Alexis de Tocqueville, George Washington memorably displayed this presidential magnanimity when he kept America out of the war between France and Britain, despite the strength of American public sympathy for France. “The simplest light of reason,” Tocqueville observed, showed that America had nothing to gain, and much to lose, from being drawn into a war between these two titans. Nevertheless, he continued,

The sympathies of the people in favor of France were…declared with so much violence that nothing less than the inflexible character of Washington and the immense popularity he enjoyed were needed to prevent war from being declared on England. And, still, the efforts that the austere reason of this great man made to struggle against the generous but unreflective passions of his fellow citizens almost took from him the sole recompense that he had ever reserved for himself, the love of his country.

In other words, Washington wanted no reward for public service beyond the esteem of his fellow citizens. He was willing to endure public criticism, and even abuse, to do what was right for the country.

This brings us to the two men with whom Presidents’ Day is most obviously connected: Washington and Abraham Lincoln, both of whom have February birthdays (Lincoln’s on the 12th and Washington’s on the 22nd). While many presidencies have been dedicated to the routine (but nevertheless demanding) administration of the nation’s business, the lives of these two men remind us that our country will encounter crises in which its fate depends on the virtues, exertions, and fidelity of a single person.

The other leaders of the founding generation openly spoke of Washington as the Revolution’s indispensable man. He commanded the confidence of the whole nation while guiding it through the War of Independence and the creation, ratification, and implementation of the Constitution. Similarly, history suggests that no politician other than Lincoln could have steered America through the Civil War with such a remarkable combination of moral clarity and determination, along with flexibility and generosity of spirit.

We can learn much about true political excellence from studying the virtues that Washington and Lincoln demonstrated throughout their public careers: their patriotism (understood both as love of the country and its people and a dedication to upholding its political principles), their prudence (always clearly discerning the goals the country needed to attain, but wisely changing tactics as the times called for a different approach), and their impressive combination of toughness and humanity. Both were willing to use force to command respect for the just prerogatives of the federal government—Lincoln in the cataclysm of the Civil War, Washington in the smaller but still critical test of the Whiskey Rebellion, among others. And both were equally eager to pardon their fellow countrymen who were willing to cast off the role of rebels and resume the role of loyal, law-abiding citizens.

Besides meditating on the virtues each displayed, we do well also to consider the many sacrifices these men made on America’s behalf.

Lincoln gave his life in the nation’s service as much as anyone who died fighting in the Civil War. He did so, moreover, consciously: he had faced threats of assassination ever since he began his journey to the nation’s capital to assume the presidency.

Washington—less spectacularly, but no less generously—gave his life gradually to his country. He spent eight grinding years of his prime leading the Continental Army. And then Washington came out of retirement to preside over the Constitutional Convention—and he then dedicated another eight years in old age to serve as the nation’s first president, spending considerable thought, anxiety, and labor in putting our political institutions on a firm footing. Additionally, he was willing to come out of retirement yet again to lead the American army in the event of war with France in the late 1790s.

Honoring men like Washington and Lincoln—and other extraordinary figures like them who have given up successful private careers and risked assassination to lead the country in uncertain times—involves a certain enlightened self-interest. If we honor such men, we are likely to get more of their kind in the future, when we may well need them again.

But honoring them is also more immediately beneficial, apart from such calculations. As moral beings, we know that gratitude is good in itself. When we are grateful to benefactors and give honor to those who are genuinely excellent, we make ourselves more human in the best sense—and better able to discharge our own duties as citizens.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How American Parents Turn Their Daughters Out.

No future awaits those who rage against family, work, and community.

United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo delivered the keynote address at the Claremont Institute's 40th Anniversary Gala as this year's recipient of the Institute's Statesmanship Award.

Wokeness is threatening our nation's historic sites.