Mr. Lincoln Leaves Washington

Wokeness is threatening our nation's historic sites.

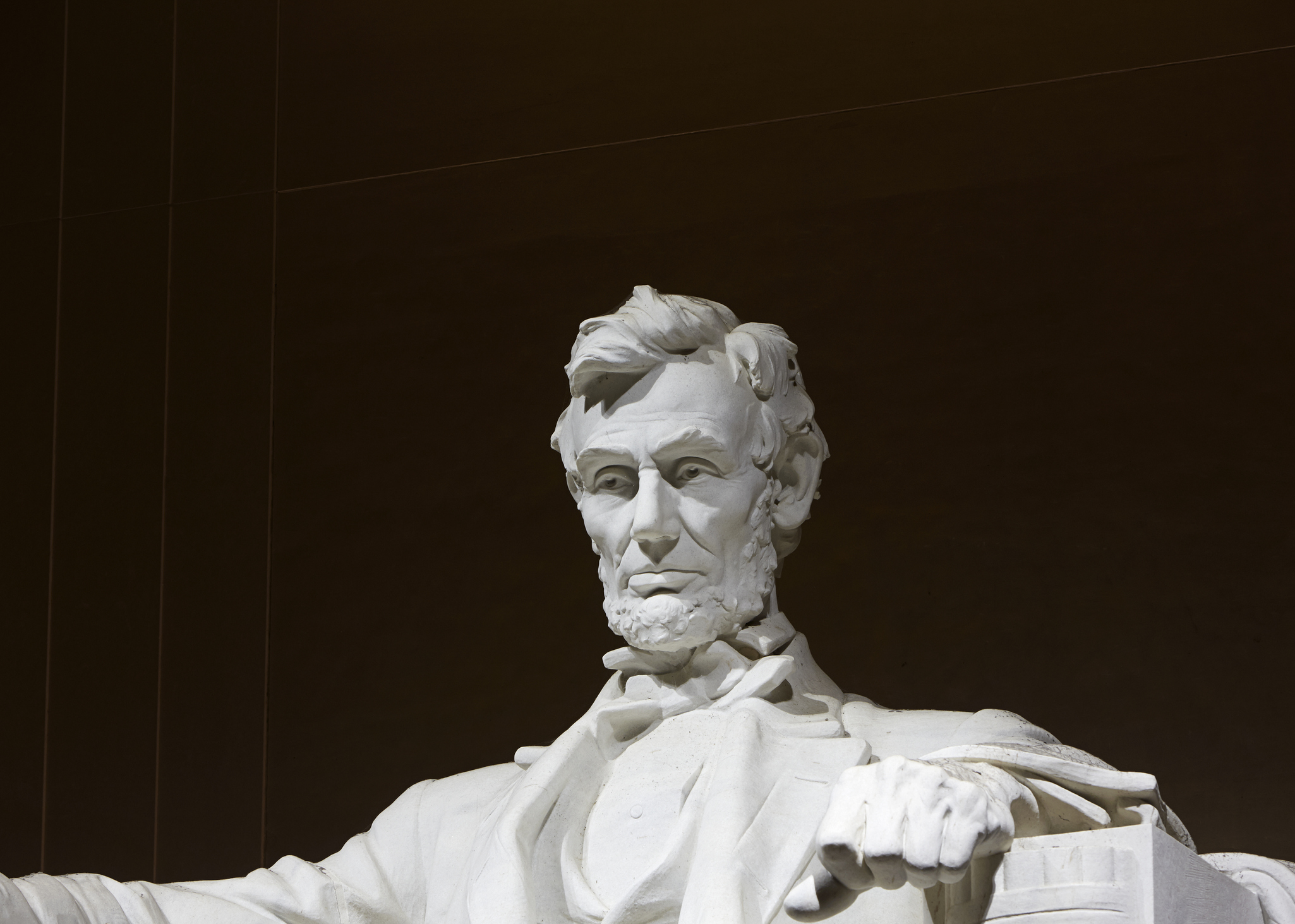

Kentucky is the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln, but Washington, D.C. is home to the Lincoln Cottage. It was there that he wrote the final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. As president, Lincoln spent several summers in the house, which today is open to the public for tours.

The visitor’s center contains a few exhibits, and the Cottage offers programming and lesson plans for teachers and students. Unfortunately, some of this curriculum downplays Lincoln’s accomplishments, as part of a larger effort by museums to infuse Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) into classrooms.

The Lincoln Cottage is not as popular as the more magnificent presidential houses, like Mount Vernon or Monticello. Only 337,000 people have toured the Cottage since 2008, whereas about 500,000 visit Monticello each year.

The visitor experience, too, is lackluster in comparison. The rooms are sparsely furnished; the guides not as practiced. While tours, of course, vary and many guides offer a modest presentation, contextual explanations are often lacking. One guide even had the audacity to contend that Lincoln was a racist who did not believe blacks and whites are fundamentally equal, an egregious statement.

The exhibits, though limited in number, are mostly evenhanded. While Lincoln’s accomplishments and the significance of the Emancipation Proclamation are not the predominant focus, the Lincoln Cottage is not as deficient as some other historic sites in presenting core information.

While the Cottage does only a fraction of the business done by Monticello, its influence is not limited to those who pass through its doors. The Lincoln Cottage is in the business of hosting educational programs and producing lesson plans, some of which have an underlying tone of activism and Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). SEL began as a non-ideological effort to teach children skills like “self-awareness” and “social awareness,” but those skills have now been reinterpreted in a controversial and political manner. In practice, SEL has teachers act as therapists, sometimes asking students highly sensitive questions about their beliefs, family, or sexuality. Concerningly, many museums and historic homes are promoting SEL and Critical Race Theory (CRT), which encourage the viewing of the world through the lens of race and placing groups into categories of “oppressed” and “oppressor.”

At a recent conference hosted by the American Association for State and Local History, museum leaders brainstormed how to undermine parents and legislators in order to smuggle and preserve the teaching of CRT in the classroom. The discussion began with the acknowledgement that, while the public is largely aware that CRT is taught in schools, few realize it is being promoted by museums. Consequently, museum leaders “should take advantage of this loophole by creating partnerships with teachers to continue teaching students critical race theory through field trips and guest speakers.”

The Lincoln Cottage is among such museums. Its Open Field Project for grades 3 through 12 meets the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning’s (CASEL) standards across the core competencies of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and responsible decision-making. According to Max Eden, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, CASEL infused SEL with CRT-aligned ideology in 2020. As Eden notes:

In “Transformative SEL,” “self-awareness” encompasses “identity,” with “identity” defined now through the lens of “intersectionality.” “Self-management” encompasses “agency,” with “agency” defined through “resistance” and “transformative/justice-oriented” citizenship. “Transformative SEL” also embraces “culturally relevant/responsive” pedagogy. This approach was pioneered by Gloria Ladson-Billings, the professor who brought Critical Race Theory to K-12 education.

The Cottage’s lesson plans address topics like Reconstruction, the Cottage itself, Equal Protection, and the Emancipation Proclamation. Some rely on primary sources and have good content. But there are few on Lincoln’s accomplishments. Students will be asked to read the lyrics of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” a song from the 1930s about lynching, but not the words of the Gettysburg Address.

The underlying tone of some lesson plans is that Lincoln wasn’t that remarkable or his achievements that significant. One plan outlining why the Civil War was fought (which does encourage students to analyze the Second Inaugural Address in detail) contends that Lincoln’s greatness stems from his martyrdom: “Before his death, few people had suspected his greatness, but his sudden and dramatic death erased his shortcomings and made people remember him for his good things.” The lesson plan really announces truly that it comes to bury Caesar, not to praise him.

The plan also asserts that the Emancipation Proclamation “freed the slaves in not-yet-conquered Southern territories, but slaves in the Border States and the conquered territories were not liberated since doing so might make them go to the South; Lincoln freed the slaves where he couldn’t and wouldn’t free the slaves where he could.” This explanation, aside from being garbled, is misleading. Lincoln took an oath to uphold the Constitution and did not believe he had constitutional authority to interfere with slavery in the North. The Emancipation Proclamation was a military order, and so he could exercise it only against those states in rebellion.

In contrast to the Cottage’s lesson plan, the Bill of Rights Institute, a civics education nonprofit, has an e-lesson on the Emancipation Proclamation which notes that it “was an essential first step by the U.S. government toward abolition…. By giving the war a new moral purpose, Lincoln changed its character. He showed that the time had come to make the nation’s policies align with its promise as stated in the Declaration of Independence: ‘…all men are created equal….’”

The Lincoln Cottage’s lesson plan on the Emancipation Proclamation asks students to examine early as well as final drafts of the Proclamation and debate if the document was groundbreaking or “too little too late.” If students are properly prepared, a debate is a fair method of tackling such questions and being able to read and wrestle with primary texts, an important skill. Answering this question requires a great deal of context to reveal the prudential decisions Lincoln had to make when faced with immense challenges, which encourages a proper appreciation of Lincoln’s remarkableness.

A more concerning element of the curriculum is the promotion of advocacy. In the lesson plan on “The Failure of Reconstruction,” students are asked to write a letter to the editor because, “Letters to the editor are great advocacy tools. After you write letters to your members of Congress, sending letters to the editor can achieve other advocacy goals because they: reach a large audience, are often monitored by elected officials, can bring up information not addressed in a news article, create an impression of widespread support or opposition to an issue.”

Turning students into activists is a growing trend in educational curriculum. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) has engaged in teacher training programs centered on “social justice” activism since the nineties, and their radical materials promote both CRT and LGBTQ content. The SPLC is an extremist organization that labels those who disagree with its ideology “hate groups.” Daniel Pipes of the Middle East Forum has called them “a left-wing hatchet group, using its accumulated prestige to go after legitimate organizations and individuals.” They are “a hugely rich institution with a formidable reputation lacking a raison d’etre or even a moral conscience.”

The Lincoln Cottage invited Seth Levi, chief strategy officer for the SPLC, to speak at a Cottage event in 2017 and appear as a guest on a podcast episode called “Was Lincoln a racist?” Mr. Levi’s role at the SPLC is to grow and develop its action fund. On the podcast, he remarked that studying presidents can be an exploration of what people do with power. “Lincoln and others had that power and did come up short,” he asserted. “…they could have done more and could’ve changed the trajectory of the country even more, but they chose not to use that power.” The Lincoln Cottage’s Director of Programming, who designs SEL content, responded that she often thinks about her power as a white woman.

The Lincoln Cottage is not the only historic site developing curricula or engaging with the SPLC. As I have previously documented, James Madison’s home of Montpelier has invited the SPLC’s involvement on multiple occasions and is creating anti-racist curriculum for use in Virginia public schools. Both Montpelier and the Lincoln Cottage are owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which owns 27 sites around the country.

The state of America’s museums and historic sites is cause for concern, especially as they are influencing the most impressionable and innocent among us: our children. This is an assault on what is most precious, just as it is an effective strategy. If our children do not know of America’s triumphs, they will not be motivated to fight for America’s future or their own. If that happens, as Abraham Lincoln articulated, we ourselves will be our “author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

On campus, today's forlorn meritocrats no longer believe what the apparatchiks are teaching them.

Libertarianism again fails natural right.