America’s aesthetic movements must resist commodification.

Memento Mori

Spend your life preparing for death rather than ignoring it

The bones of around 4,000 deceased monks decorate the walls of the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. Inside, there is an inscription that reads, “What you are now, we once were. You soon will be what we are.” Once a place of prayer and reflection, it is now mostly regarded as an oddity for tourists. Many people visiting it today likely leave with the conclusion that the dark medieval society that allowed for such a display was much too obsessed with death.

But that stark reminder of death simply represents a reality that has existed in nearly every society and culture for millennia. Death was something that was seen as necessary to contemplate throughout one’s life. It was unavoidable. One could expect that, from a young age, one would have many close and personal encounters with death: the early death of a sibling or parent was a distinct possibility. At any moment, a plague could wipe out a large percentage of your town’s population. You could suddenly be called to war or be forced to take refuge from pillaging invaders. Not only was death inevitable, it could come at any time. The bones in the crypt were simply an explicit reminder of what one already knew.

Now, more than ever before, thinking about death is easily avoidable. Increased technology and medicine mean less people die unexpectedly. More people die in hospitals rather than at home. Even the process of death is more easily ignored. We put our elderly in nursing homes to slowly live out their last days in isolation from the rest of society. There they can be forgotten and ignored, with the only interaction with humans being brief encounters with overworked nurses and the possible visit from a committed family member.

Worse still, some seek to eliminate the process of death entirely. Assisted suicide is encouraged for the ‘unproductive’ and ‘burdensome’ people in our society. Western nations further down the road of destruction than our own try to make suicide as easy as possible.

As a result, many people live their lives in ignorant complacency, never considering what death means and what might come as a result. Though no one would admit that they think they are immortal, many people live that way. Once life was short and eternity was everything. Now life is everything and eternity is forgotten.

Since there is nothing to consider beyond our personal ‘lived experience,’ there is no need to address big questions that go beyond the self. There is no need to discover what might come after death, let alone prepare for it. One’s life can be lived in shallow, bland agnosticism, with no need to discover an eternal order to live by or an eternal home to strive for.

Of course, even in the modern world, death can never be completely ignored or avoided. But because the modern mind has tried to push all thoughts of its inevitability to the side, people have no idea how to deal with it when confronted head-on. Instead of seeing death as a reason for sober reflection, too many people can only react with overriding fear and hysteria.

The response to COVID is the greatest example of this happening on a large scale. People freaked out because they realized they were mortal. When confronted with the slim possibility of a slightly premature death, all of normal life had to be stopped. Living fully was condemned because of the possibility of death.

Because what is truly inevitable is perceived as unexpected, society treats every death as a tragedy. To be sure, death is certainly significant, and the grief and sorrow that come as a result of being separated from one we love is an appropriate response. But not every death is a tragedy.

Death can be the culmination of a life well lived and the entrance into eternal life. It is the necessary end to any life. Death itself can be a glorious triumph (e.g.: Jesus, Socrates). What is a tragedy are those who die unprepared. If you wait to prepare for death until the end of your life, you may be too late. Instead of spending your life trying to avoid or ignore death, your time would be much better spent in preparation for it.

Though it is easier to ignore today, death is just as real now as it was a thousand years ago. More people in America today may die from heart disease than from famine, but everyone still dies one way or another. Naturally, it is still just as important to think about. Such an attitude toward death can help us combat the apathy that plagues so many in American society and force us to contemplate eternal truths that go beyond the shallow trends of our time.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Conservatives are right to challenge libertarians, but they must avoid Hawleyism.

Our decadent elite cannot survive our technological transformation.

Political prudence requires reason—which is why a "conservative rationalism" that embraces universals and particulars alike is needed now more than ever.

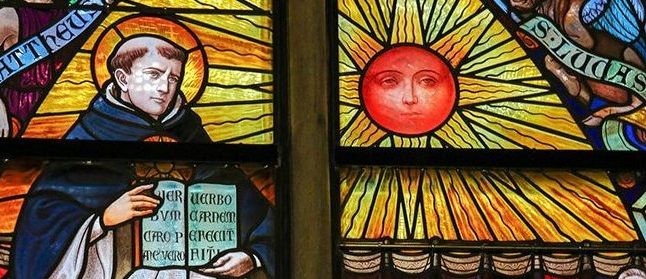

Just as it belongs to religion to give worship to God, so does it belong to piety to give worship to one's parents and one's country.

The Founders' America protects a sphere outside of politics where men and women can worship God the Redeemer according to the dictates of conscience and the judgment of reason informed by revelation.