Thanksgiving Wasn't Always a Source of National Unity.

The Laws of Nature and Nature’s God

The Founders' America protects a sphere outside of politics where men and women can worship God the Redeemer according to the dictates of conscience and the judgment of reason informed by revelation.

An American student visiting Oxford University, after passing by Lincoln College and Jesus College, told her tour guide that she had a hard time telling the difference. As the joke goes, the tour guide replied, “Yes, most Americans do have a hard time telling the difference between Lincoln and Jesus.”

In some quarters, Lincoln is remembered as the savior of the Republic, a secular saint or even a messiah: the son of the fathers who was sent into the world to carry out a mission for which he took an assassin’s bullet on Good Friday in 1865. Lincoln, however, rarely appealed to the Savior’s authority in his letters, orations, and public documents. A search of Lincoln’s collected works uncovers over 300 invocations of God (and hundreds more if we include terms like “Almighty” or “Creator”), but few even indirect references to Jesus.

In his debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln did quote Matthew 5:48—“As your Father in heaven is perfect, be ye also perfect”—but only as a metaphor to argue that the Declaration of Independence should operate as Scripture for the American political order, as a standard to approximate in public life even if it cannot be fully realized this side of heaven. “So I say in relation to the principle that all men are created equal, let it be as nearly reached as we can,” Lincoln insisted. The other famous quote from Jesus that appears repeatedly in those debates with Douglas is that a “house divided against itself cannot stand,” a Gospel reference Lincoln used to underscore the impossibility of maintaining republican government that is half slave and half free.

Why so many references to God but so few to Jesus? Lincoln gave a clue in his 1860 speech at Hartford, where he says that the wrongness of slavery can be “clearly proved by natural theology, apart from revelation.” In invoking the God of natural theology in public life, Lincoln was well within the mainstream of the American political tradition, which begins in its foundational document by appealing to the authority of the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” before affirming the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.”

As Lincoln knew well, America’s civil or political religion has long taken its bearings from God the Creator, known by reason rather than revelation. Does this mean, as the subtitle of Matthew Stewart’s recent book Nature’s God suggests, that the American Republic was built on foundations that are heretical to Christianity? Stewart is just one among many scholars who see the God of Abraham and the God of Nature as rival and mutually exclusive deities that rest on rival and mutually exclusive narratives about human nature and human destiny. In Stewart’s interpretation, the God of Nature is the god of the philosophers, a pantheistic being indistinguishable from nature.

Must one who believes in a personal God who stands outside of creation and who reveals himself as the “I AM”—as the very ground of being—therefore part ways with the American founding on account of its alleged deification of nature? If Stewart were right, perhaps, but he is not. To understand why it is helpful to look at the question from the perspective of the Reformed theological tradition in which many of the founders were educated.

As Stephen Grabill notes in his important book Rediscovering the Natural Law in Reformed Theological Ethics, first and second generation reformers “developed increasingly sophisticated and comprehensive formulations of natural law that they situated in the wider context of the great moral tradition with Aristotle, Cicero, Augustine, Aquinas, Scotus, and many others.” Central to Reformed doctrines of natural law was the doctrine of the duplex cognitio dei, or the twofold knowledge of God, discussed at length in the first books of Calvin’s Institutes and elaborated upon by subsequent theologians. Calvin taught that all human beings have knowledge of God the Creator, but that it is only by revelation that we have knowledge of God the Redeemer.

Crucially, according to Calvin, our knowledge of God the Creator is sufficient for “earthly things” including “matters of policy and economy, all mechanical arts and liberal studies.” With respect to politics, Calvin insisted that there can be a legitimate diversity in constitutional forms based on prudential judgments that vary according to circumstance, “provided they all alike aim at equity as their end.” Equity or justice—“as it is natural”—is “nothing else than a testimony of natural law and of that conscience which God has engraved upon the minds of men” and this natural equity ought to be the “goal and rule and limit of all laws.”

It should be no surprise, then, to see committed Christians among the founders joining their more skeptical and heterodox colleagues in a project to establish political rule that approximates, so far as it can, natural justice. The basic natural-law framework carried into Reformation theology from the medieval scholastics gives Christian theological warrant for affirming allegiance to a political regime that is founded on the self-evident truths in the Declaration of Independence. That regime, which takes its bearings from the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God and sets natural justice as the goal and rule and limit of all laws, also (and for just this reason) protects a sphere outside of politics where men and women can worship God the Redeemer according to the dictates of conscience and the judgment of reason informed by revelation.

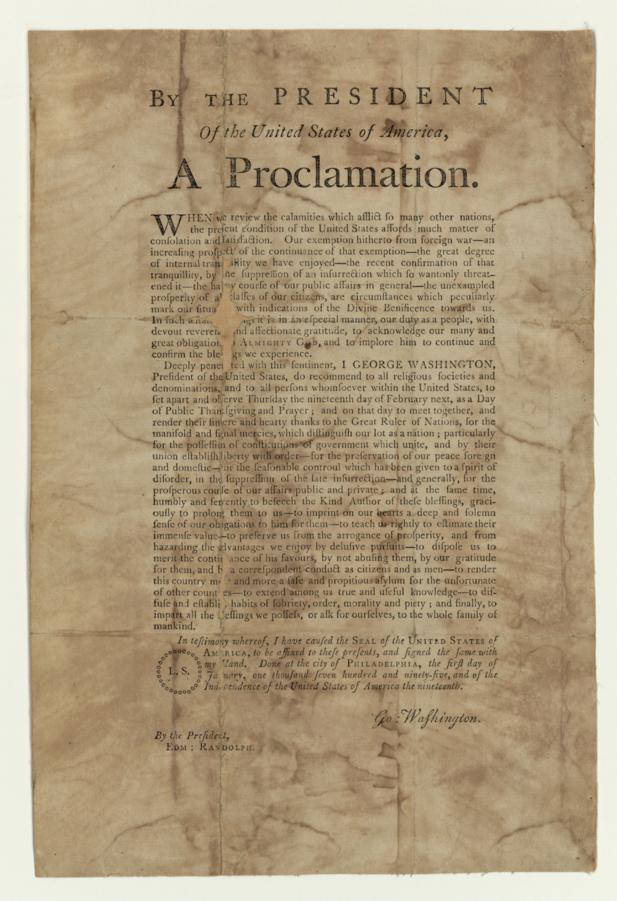

The founding may not be exclusively Christian, but from a Christian perspective that is okay. It is enough that Christians can in good faith join in this political project, following Lincoln’s admonition in his last Thanksgiving Day proclamation—delivered only few months before his death on Holy Saturday—and join together with their fellow citizens to offer gratitude to “Almighty God the beneficent Creator and Ruler of the Universe.”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

We should be thankful for the sheer wonder of being.

The Genuinely American Debate over Federalism and Thanksgiving.

Allen Guelzo, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Bottum, and Justin Dyer on the thought and action of Lincoln's Thanksgiving and his wrestling with God.