Start with online speech coalition-building.

A New Tech Agenda Requires Expertise and Realism

Conservatives are right to challenge libertarians, but they must avoid Hawleyism.

The editors of influential conservative publications—including The American Mind, First Things, the American Conservative, and others—have called for a “tech new deal,” arguing the right has lost its ability to meet the challenges of the digital era. Like its original namesake, or the more recent “green” version, this “new deal” entails a proclamation that there’s a crisis. And an affirmative agenda to get us out of it.

The crisis, the letter proclaims it, is a failure of conservative institutions to adapt to the times and correct for deficiencies in the old thinking about the role of technology in society.

No longer are conservatives all “super pumped” about trying to be the party of Uber. In the Trump era, many conservatives are souring on Big Tech, which is causing a schism with the libertarian part of their coalition. Among their fears is that conservative ideas—particularly those about life and marriage—will be pushed out of a public square captured by woke tech companies in San Francisco.

Other grievances include anxiety about the corrosive effects of technology, particularly social media, on family and community. There is also discomfort with the consequences of a “move fast and break things” approach to technologies like facial recognition and gene editing—which we’ve already seen in China. Critics like Senator Josh Hawley have also argued today’s big tech companies aren’t focused on the right problems, putting the greatest minds of our generation at work to make us more addicted to our phones (as opposed to curing cancer or exploring the stars).

And so, the tech new deal’s authors argue, it is time for new thinking to replace old orthodoxies about the role of government and how we think about innovation. But despite their enthusiasm, it doesn’t seem like they’re completely sure what this new agenda entails or what comes next.

This scenario isn’t unique to the domain of tech policy. There have been growing tensions within the Right about free-market orthodoxies across a range of policy issues. But even as the Trump-era conservative coalition moves away from libertarianism—which tends to be more strongly represented in D.C. institutions than the Republican base—it should be careful not to go too far.

Forgiveness or Permission?

While there are legitimate criticisms of the “old deal” on tech and the pathologies of its institutions, they also got a lot right. As with religion, so with tech: the worst criticisms are more fairly applied to a philosophy’s adherents than to the philosophy itself.

The prevailing framework for thinking about innovation policy on the libertarian right is “permissionless innovation,” a concept developed and popularized by Adam Thierer at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, which argues that innovators should generally be free to experiment. Thierer suggests the origin of the term can be traced to Grace Hopper, a famous computer scientist and Rear Admiral in the U.S. Navy, who said in a 1986 interview with CHIPS Ahoy magazine: “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.”

In Thierer’s more expanded book version, he argues a central question in innovation policy is one of permission and risk tolerance: “Must the creators of new technologies seek the blessing of public officials before they develop and deploy their innovations?”

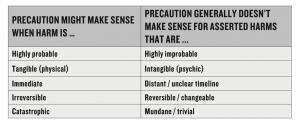

This view of “permissionless innovation” should be contrasted with the “precautionary principle.” The latter holds that the burden is on innovators to prove their technology will not cause any harm, whereas the former holds new innovations should be permitted by default, and entrepreneurs should generally be free to experiment and self-correct. In general, under this view, harms should be addressed by government ex post. In some circumstances, however, precaution may be warranted. In his book, Thierer provides the following rubric:

Source: Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation, p. 33

Why place such a high value on making the future happen sooner? For one, innovation is a key driver of economic growth and prosperity. Over the last century or so, technology has uplifted the lives of Americans from toil and drudgery to wealth and comfort.

This progress is a relatively recent phenomenon for humanity. As economist Joel Mokyr put it: “for 97 percent or so of recorded history, the stationary state well-describes the long-run dynamics of the world economy. Growth was slow, intermittent, and reversible.”

This perspective is a valuable one to bear in mind as we contemplate putting the brakes on the engine of scientific and technological advancement. Perhaps it would be prudent, as Thierer suggests, to be careful not to undermine the benefits of past and future innovations as we try to mitigate potential harms. After all, we are all poor compared to where we might be in the future, just as our ancestors were poor compared to us. Is it not immoral to undermine the progress of future generations?

For all the criticisms heaped on social media (many well-deserved), it still delivers considerable value as an information channel and network between our friends and family, a substrate upon which niche communities can be formed that otherwise never would have existed. And despite our anxieties about Big Tech’s concentrated power, it is hard to argue companies like Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft don’t deliver a substantial net positive economically, socially, and with respect to America’s place in the world.

Of Garage Inventors and Astronauts

At the same time, the catechism of permissionless innovation would be easier for non-libertarians to internalize if its adherents took addressing harms more seriously. While Thierer puts important caveats in the right places, these are often ignored by the philosophy’s zealous proponents. And even in Thierer’s book, addressing harms and thorny edge cases garners relatively little ink (although he does explore them elsewhere). You will be unlikely to find many libertarian think tanks calling for new agencies, added expertise, higher-quality talent in government. Nor are libertarians thinking hard about new regulations or remedies for the threats to family life, national security, and international relations posed by technology.

When encountering appeals to “permissionless innovation” in the wild, one might reasonably wonder whether its proponents are engaging in polemic or earnest philosophy. All too often, its rhetoric seems like a legitimizing facade for anarcho-capitalists, tech bros, and cynical corporate flacks.

For many traditional conservatives, even the genuine article comes off as counter to the rule of law. As Thierer remarked in an interview, “What is Uber if not the biggest law breaker in the world today? And God bless them for it!” (His book-length version of this thesis, out in April, is aptly titled Evasive Entrepreneurs.)

To be fair to Thierer, I’m glad Uber exists. And it certainly might not if Travis Kalanick wasn’t as aggressive in skirting regulatory boundaries. It’s also worth remembering that Uber’s tactics wouldn’t work if they weren’t serving populist ends—Uber was able to beat regulators only because popular pressure forced local governments to give up on protecting incumbents with an inferior product. Nonetheless, this full-throated endorsement of rule breaking may go too far for many conservatives.

A more serious problem with the narrative of “permissionless innovation” is that it feeds into the conservative mythology of deregulation as the sole concern of innovation policy, wherein the fabled garage inventor is standing by waiting for big government to get out of the way.

While Thierer has a more nuanced view, he still suggests the proper role of government is essentially to get out of the way. This retconning edits out the substantial role of state capacity and government investment—such as through the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense—in creating Silicon Valley and advancing America’s technology leadership.

If it were 1957 and we were facing another Sputnik moment, with our adversaries eclipsing us in technological prowess (as China may soon do), many libertarians would almost certainly oppose the creation of DARPA or the Apollo Program (or other instruments of state capacity). Historically, this would have aided the Soviet Union, while delaying or making us lose out on the myriad advances these institutions helped create such as the Internet, GPS, and smartphones. A future innovation policy platform must not make this ideology-driven error of omission.

A Story of Institutional Decadence

Beyond the limitations of their philosophical approach to innovation, our preeminent right-leaning think tanks suffer from two major problems: one is waning influence, the other is weakened credibility. Many are still operating on a 1970s-era business model of how to affect policy; producing verbose white papers that few people read, lackluster ghost-written op-eds, and ineffectual convenings for beltway insiders. They’re overly concerned with issues that either aren’t that important or that they aren’t in a position to change.

Browse the top think tanks working on tech and you’ll find an abundance of coverage on big ticket issues like federal privacy legislation, Sec. 230, or telecom regulation (after all, we’ve always been at war on net neutrality). These issues are certainly important economically. But with industry groups spending tens of millions on lobbying, is it really something small nonprofits will maximize their impact on? Are these types of issues more about enabling future innovations, or protecting the business models of incumbents?

One can understand being attracted to the issues that grab the biggest headlines. But a more cynical answer is that these issues are what big companies care about and have “third party” budgets to fund.

Supporting this view, there are lots of examples of questionable dealings even among top think tanks. Beneath the surface, there’s also a cottage industry of lesser-known ones willing to put their names to anything they can make a buck on. (To paraphrase Senator John McCain, it’s not about which individuals are corrupt, it’s about the system.) In short: think tanks have a reputation problem, and they’ve earned it.

Few conservatives seem willing to break Ronald Reagan’s Eleventh Commandment not to criticize their peers (we’re all shocked, shocked, that gambling is going on here). But turning a blind eye to pay-for-play has seriously hurt everyone’s trustworthiness. Additionally, even if companies aren’t buying people’s opinions, it’s evident they are buying their attention. This has the effect of distracting top talent away from issues where they can have a bigger impact, instead putting them in the trenches for corporate lobbying wars. Lack of transparency and clear ethical norms also fuels conspiracy theories and distrust. All things considered, too many talented people in established D.C. institutions are spending their time making noise rather than shaping the future.

Beyond fist-shaking on the other side from the libertarian-leaning establishment, the nascent tech-skeptical Right is still swinging blindly looking for a piñata. Criticisms tend to be culture war propaganda and aping of half-baked progressive ideas.

These include efforts to abolish Sec. 230 to address political bias (it wouldn’t), break up America’s leading tech companies (a move which would surely empower China at our expense), or make the First Amendment governing law of the Internet (spoiler: most conservatives would hate this in practice).

Instead of seeking to punish tech companies as an end in itself, conservative tech critics need to build expertise first and articulate thoughtful policies that advance conservative ends. Rather than trying to punish and destroy, they should try to promote competition and variety—embracing competition-enhancing ideas like interoperability and data portability, or looking to enable adversarial competition by updating overzealous laws like the CFAA and our intellectual property regime (fun fact: while today you hear uniform chanting of “natural rights” when mentioning IP, conservatives used to be skeptical of Hollywood’s agenda and pro-patent reform).

Where there are concerns about potential future harms, tech-skeptical conservatives should seek to build up public and private institutions to be resilient against them. In this sense, a “new deal” approach is needed for the skeptics even more than for the libertarians.

For all their problems, the conservative critics are right that we need to do away with the “hear no evil, see no evil” philosophy exposed by some libertarians. The fact that we’re talking about a private company doesn’t mean it’s the end of the conversation.

At the same time, critics need to learn how to better use civil society pressure to get policy and product changes without invoking the blunt instruments of regulation, which will inevitably have long-term downsides for the future of innovation and America’s global competitiveness.

The “tech new deal,” wherever you come down on its pronouncements, is serving to advance self-reflection and debate on the right. This is a conversation we should welcome.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Overregulating digital technology will backfire in the end.