Root, root, root for the electors. If they don't win it's a shame.

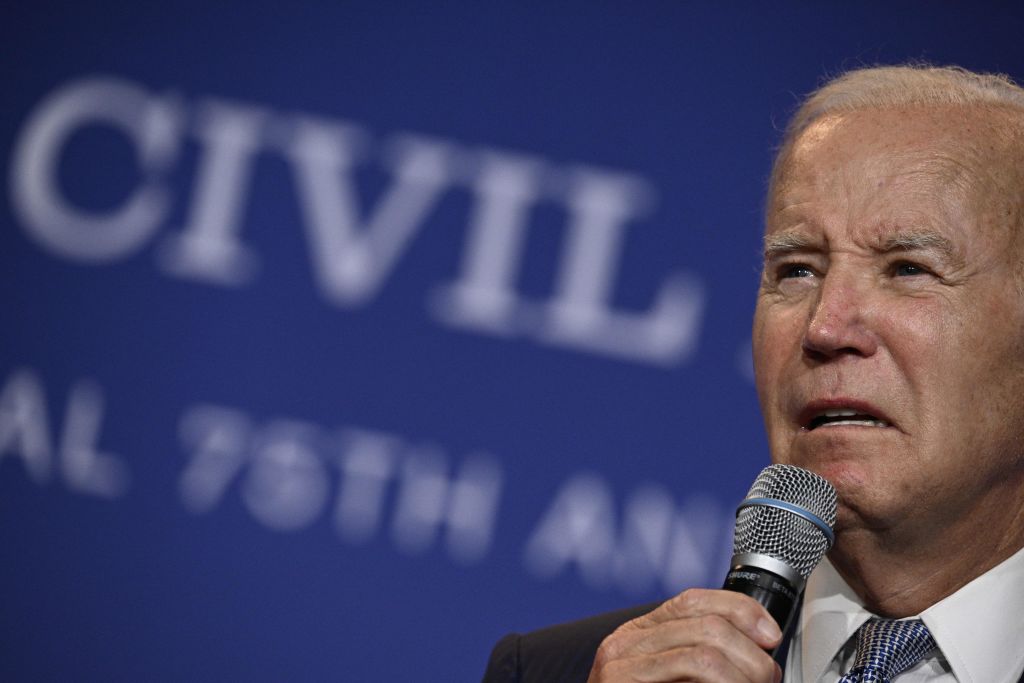

Biden Censorship Plans Take Major Hit

Despite the media’s subterfuge, Missouri v. Biden is a complete victory for the plaintiffs.

On Friday, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the government’s effort to reverse federal district court judge Terry A. Doughty’s ruling in Missouri v. Biden. On Independence Day, Judge Doughty ruled that the plaintiffs had met their burden for issuance of a preliminary injunction to block the White House and other federal agencies from communicating with social media companies to urge, encourage, pressure, or induce the deletion or suppression of content containing protected free speech.

A three-judge panel of the court of appeals unanimously agreed with Judge Doughty that the plaintiffs were likely to establish that the Biden Administration had engaged in a broad attack on free speech in violation of the First Amendment. The court replaced Doughty’s clunky 600-word preliminary injunction with a concise 83-word order that is in some respects stronger. It also agreed that all requirements for the issuance of a preliminary injunction had been satisfied as to the White House, CDC, Surgeon General and FBI, but not as to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, or Department of State.

A party seeking a preliminary injunction must establish that (1) they are likely to succeed on the merits, (2) there is a substantial threat that they otherwise will suffer an irreparable injury, (3) the potential injury outweighs any harm that will result to the defendant, and (4) an injunction will not disserve the public interest.

Given the urgency of the situation, instead of remanding the case to the district court to revise its injunction, the court of appeals issued a new injunction which will become effective on September 18, giving the government time to appeal. It ordered the White House, CDC, Surgeon General, FBI, 14 named federal officials, and all directors, administrators, employees and agents of those named to “take no actions, formal or informal, directly or indirectly, to coerce or significantly encourage social-media companies to remove, delete, suppress, or reduce, including through altering their algorithms, posted social-media content containing protected free speech. That includes, but is not limited to, compelling the platforms to act, such as by intimating that some form of punishment will follow a failure to comply with any request, or supervising, directing, or otherwise meaningfully controlling the social-media companies’ decision-making processes.”

In practice there are few differences in the scope of the injunctions. Doughty’s prohibited the defendants from coordinating with private so-called election integrity organizations. The Fifth Circuit was concerned that this could unintentionally include unnamed private institutions that also have First Amendment rights. As noted, the appeals court also excluded three agencies named in Doughty’s injunction. Conversely, by adding the words “directly or indirectly,” the Fifth Circuit’s injunction is likely to capture impermissible conduct undertaken by named and unnamed federal agencies that work at the direction of any named defendants. Its reference to algorithms closes the door on the government’s argument that it is not responsible for the platforms’ policies.

The court explained: “Under the modified injunction, the enjoined Defendants cannot coerce or significantly encourage a platform’s content-moderation decisions. Such conduct includes threats of adverse consequences—even if those threats are not verbalized and never materialize—so long as a reasonable person would construe a government’s message as alluding to some form of punishment. That, of course, is informed by context (e.g., persistent pressure, perceived or actual ability to make good on a threat). The government cannot subject the platforms to legal, regulatory, or economic consequences (beyond reputational harms) if they do not comply with a given request. The enjoined Defendants also cannot supervise a platform’s content moderation decisions or directly involve themselves in the decision itself. Social-media platforms’ content-moderation decisions must be theirs and theirs alone.”

The court observed that government control touched on “a host of divisive topics like the COVID-19 lab-leak theory, pandemic lockdowns, vaccine side- effects, election fraud, and the Hunter Biden laptop story.” In his ruling, Doughty also cited conservative-leaning speech; humor and parodies about defendants; negative posts about the economy, posts calling President Biden a liar; and discussions about gas prices, climate change, gender, and abortion.

The court explained that violations of protected speech by private companies becomes state action when, among other things, the government “coerces” or “significantly encourages” the violations. It concluded that plaintiffs likely would establish both, observing that evidence shows the defendants made public and private threats of adverse government action, including increased regulation, antitrust enforcement, and changes to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (which insulates internet companies from liability for third-party content), and applied unrelenting pressure via demands for greater censorship.

For coercion, the court explained, the question is whether the government compelled the decision through threats or otherwise intimating that some form of punishment will follow a failure to comply. The court concluded that: “On multiple occasions, the officials coerced the platforms into direct action via urgent, uncompromising demands to moderate content. Privately, the officials were not shy in their requests…. And, more importantly, the officials threatened—both expressly and implicitly—to retaliate against inaction. Officials threw out the prospect of legal reforms and enforcement actions while subtly insinuating it would be in the platforms’ best interests to comply.”

The court further analyzed the government’s action under a four-part test: (1) word choice and tone, including the overall “tenor” of the parties’ relationship; (2) the recipient’s perception; (3) the presence of authority, which includes whether it is reasonable to fear retaliation; and (4) whether the speaker refers to adverse consequences. On the first factor, it found “that the officials’ communications—reading them in context, not in isolation—were on-the-whole intimidating.” On the second factor, it found “plenty of evidence—both direct and circumstantial, considering the platforms’ contemporaneous actions—that the platforms were influenced by the officials’ demands.” On the third factor, the White House “clearly” has authority over the platforms. And on the final factor, “the officials made express threats and, at the very least, leaned into the inherent authority of the President’s office. The officials made inflammatory accusations, such as saying that the platforms were ‘poison[ing]’ the public, and ‘killing people.’”

For significant encouragement, the panel cited the Supreme Court’s decision in Blum v. Yaretsky (1982) for the proposition that “To constitute ‘significant encouragement,’ there must be such a ‘close nexus’ between the parties that the government is practically ‘responsible’ for the challenged decision…. That reveals itself in (1) entanglement in a party’s independent decision-making or (2) direct involvement in carrying out the decision itself.” The court found that officials “significantly encouraged the platforms to moderate content by exercising active, meaningful control over those decisions. Specifically, the officials entangled themselves in the platforms’ decision-making processes, namely their moderation policies.”

In analyzing the remaining factors for issuance of a preliminary injunction, the court observed the Supreme Court had held that the loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of time, constitutes irreparable injury, and that further, “the district court was right to be skeptical of the officials’ claims that they had stopped all challenged conduct.” The court rejected the government’s noxious assertion that its right to speak outweighs the public’s right to do so.

Coverage of the ruling has been subdued and misleading. The Washington Post is typical. Instead of seeing the Biden efforts as an assault on free speech, or the appeals court as sustaining Doughty’s findings, the Post reported that the Fifth Circuit objected to the administration “improperly influencing” tech companies. It quoted an attorney who said the new injunction was “a thousand times better” than what Doughty, “an appointee of former president Trump,” had ordered. The Post supported his view by observing that the appeals court “threw out” nine of the ten specific prohibitions in Doughty’s order. It did not mention that the court also eliminated the exceptions and replaced Doughty’s injunction with a comparable or more powerful order.

The New York Times reported that the court ruled that the administration “most likely overstepped the First Amendment by urging the major social media platforms to remove misleading or false content.” The Times wrote that the case “challenged the government’s ability to combat false and misleading narratives about the pandemic, voting rights and other issues that spread on social media.” It thus downplayed the “likely” legal standard with the colloquial “most likely,” falsely describing the scope of the information government suppressed, and never mentioned that the Supreme Court has repeatedly held that the government may not censor falsehoods. Only at the end of the article does the Times note that both Doughty and the appeals court generally agreed that the lawsuit involved “the most massive attack on free speech in United States history.”

Contrary to most reports, the Fifth Circuit’s ruling is a consequential step forward toward breaking the Biden Administration’s multi-pronged attack on the First Amendment.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Remarks accepting the Claremont Institute’s Henry Salvatori Prize in the American Founding, Washington, D.C., October 27, 2018.

We don’t need a revolution to find political redemption.