Digital conditions, not competing intellectuals, will make it so.

Tyranny and the Politics of the Common-Good

A response to Adrian Vermeule

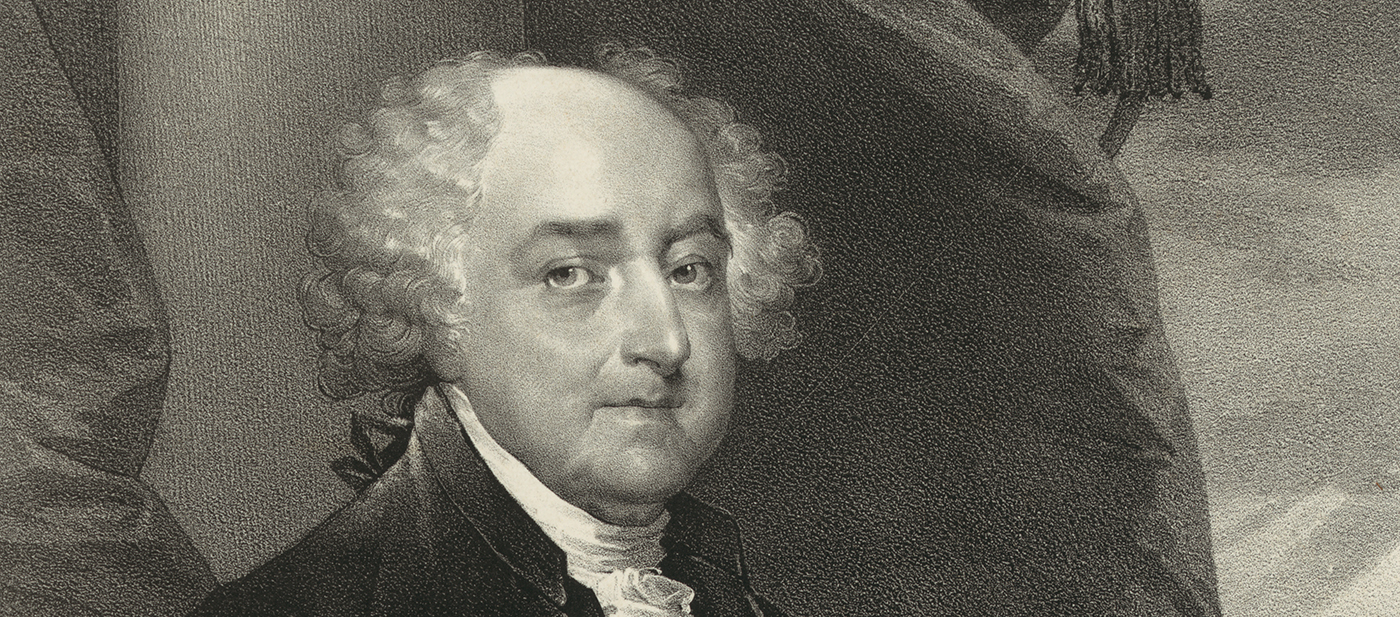

In 1765, John Adams published a powerful essay on ecclesiastical and political despotism. His thesis was simple: altar and throne, church and state, had merged in seventeenth-century Europe to form a new kind of tyranny that now threatened eighteenth-century America. Adams feared that a variation of the canon and feudal law was coming to America via the Stamp Act and recent attempts by British imperial officials to establish an Anglican episcopacy in the colonies.

Were Adams to visit America today, he would no doubt be appalled to learn that a professor of his alma mater is a proponent of a new form of the canon and feudal law. Adrian Vermeule, a professor at the Harvard Law School and the dyspeptic enfant terrible of Catholic integralism, published an essay recently in The Atlantic that argues for “common-good constitutionalism,” which should be grounded “on the principles that government helps direct persons, associations, and society generally toward the common good, and that strong rule in the interest of attaining the common good is entirely legitimate.”

What exactly does Vizier Vermeule mean by the “common good”?

Vermeule answers with a few glittering generalities but with nothing that actually means anything. The “common good,” he says, must be informed by “substantive moral principles” that “should read into the majestic generalities and ambiguities of the written Constitution” via the “general welfare” clause. The undefined moral principles that Vermeule would foist on the American people include: 1) “respect for the authority of rule and of rulers”; 2) “respect for the hierarchies needed for society to function”; 3) “solidarity within and among families, social groups, and workers’ unions, trade associations, and professions”; 4) “appropriate subsidiarity, or respect for the legitimate roles of public bodies and associations at all levels of government and society”; and, 5) “a candid willingness to ‘legislate morality.’” For Vermeule, the Constitution’s “general welfare” clause is a fill-in-the-blank check subject to the whims of whoever holds power.

And how is this common-good constitutionalism to be put into effect?

Vizier Vermeule asserts that rulers should not be “tethered to particular written instruments of civil law or the will of the legislators who created them.” Instead, common-good law should be viewed as “parental” or as “a wise teacher and an inculcator of good habits.” Vermeule thus divides Americans into “rulers” and “subjects,” so that rulers can rule and subjects can obey. His common-good rulers will “encourage subjects to form more authentic desires for the individual and common goods, better habits, and beliefs that better track and promote communal well-being.” Apparently Vermeule’s ruling class knows better than regular folks what their “authentic desires” should be, and he’s prepared to use coercive State power to bend the wills of Americans toward his undefined higher good.

Vermeule also favors regulating speech and property rights. He supports giving the government greater power to judge and control “the quality and moral worth of public speech,” and he favors regulating what he calls “Libertarian conceptions of property rights and economic rights.” Vermeule’s ruling elite will therefore assume the necessary power to “protect the vulnerable from the ravages of pandemics, natural disasters, and climate change, and from the underlying structures of corporate power that contribute to these events.” As an apparent disciple of the child-philosopher-queen Greta Thunberg, Vermeule believes that the structures of corporate power contribute to pandemics, natural disasters, and climate change!

Ultimately, Vermeule is a proponent of a common-good Deep State (he calls it a theory of ragion di stato—“reason of state”) that would massively increase government power over the “selfish claims of individuals to private ‘rights.’” In normal times, serious thinkers would treat Vermeule and his rump faction of Catholic TradCons as amusingly nutty, but these are not normal times. We live in an era of social ferment and violence, when disturbing ideas from both the radical Left and the reactionary Right are bubbling to the surface. Both camps want to use coercive State power to force their particular view of the “common good” on everyone else.

The time has come for our common-good reactionaries to explain themselves. Before we turn over the reins of government to Vermeule so that he can help us to “form more authentic desires” and “better habits,” we deserve answers to a few simple questions:

- What is the “common good”?

- Where does it come from?

- How is it known?

- Who determines what the “common good” is?

- What role should government play in promoting and enforcing it?

- What are the punishments for those who violate the laws enforcing the “common good”?

Because the philosophic burden of proof is always on those who assert the positive, Vermeule must tell us what he means by the “common good” and how it cashes out politically and legally. Otherwise, he’s just blathering gaseous platitudes with no basis in objective reality.

As we wait in vain for answers to these questions, here are six problems with common-good politics.

First, the common-good school of thought assumes, without proof, that there is one, absolute, universal, eternal, knowable “common good” that should guide public policy despite the fact that there are innumerable and competing definitions of the “common good.” Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Rastafarians, and atheists all have their own view of what the “public interest” is and the kinds of policies that will promote it. The same is true for communists, socialists, fascists, Nazis, liberals, conservatives, libertarians, and anarchists. Other than their arbitrary assertions, Vermeule and his neo-reactionary friends have done nothing to demonstrate the truth and superiority of their view of the “common good” over any another.

Second, the problem with common-good politics in a liberal democracy becomes manifest when rival factions compete with one another for political power in order to impose their view of the “common good” on everyone else. Case in point: the political fight over controlling what is taught in America’s government schools is always a fight over competing visions of the “common good.” When Christian conservatives in Kansas capture control of the education system and force the children of secular liberals to learn creationism, they do it in the name of the common good. And when secular liberals in Massachusetts capture control of the education establishment and force the children of Christian conservatives to read that Heather Has Two Mommies, they do it in the name of the “common good.” The politics of the common-good always becomes a dog-eat-dog competition for power.

Third, until recently, Left- and Right-wing proponents of the “common good” were reverse mirror images of each other. Liberals typically wanted social freedom and command-style economics, whereas conservatives typically wanted economic freedom and command-style morality. The Left believed that government must determine which material goods should be common to all people, how such goods were to be produced, by whom, and how they shall be redistributed. The Right believed that government must determine which spiritual goods should be common to all people, and how and by whom such goods will be produced and enforced. Today, however, the nihilist Left and the reactionary Right meet in the middle: both camps want power over the material and spiritual realms. The Left calls for total control over what can be thought, said, seen, heard, and done, and the Right calls for partial control over what can be thought, said, seen, heard, and done. The differences today between common-good socialists and common-good conservatives are of degree only.

Fourth, does anyone seriously believe that Harvard professors, the Vatican’s College of Cardinals, or Deep State bureaucrats actually know what is best for ordinary Americans better than ordinary Americans? Does anyone seriously think that an elite corps of progressive or conservative social engineers can “know our authentic desires” or know how to better live our lives? As Thomas Jefferson wrote: “State a moral case to a ploughman and a professor. The former will decide it as well, and often better than the latter.” Does anyone seriously think that government virtucrats can better determine the moral lives of millions of people than those people themselves? Vizier Vermeule screams for the State to use its coercive force to impose the “common good” on ordinary people who mostly just want to be left alone.

Fifth, virtually every tyrant throughout history has used the “common good” to justify acts of violence and oppression. Jacobinism, socialism, fascism, communism, and Nazism all claimed to serve the common good. The Jacobin Gracchus Babeuf said of his animating political purpose, “We reach for something more sublime and more just: the common good or the community of goods! No more individual property in land: the land belongs to no one. We demand, we want, the common enjoyment of the fruits of the land: the fruits belong to all.” Or, as the 1920 NAZI party platform put it: “The Common Good Before the Individual Good.” One could write a very long book cataloguing the crimes committed by those who speak in the name of the “common good.”

Sixth, common-good harpies of the Left and Right misunderstand what virtue and moral action are. They fail to understand that morality to be moral requires uncoerced, free choice. Coerced virtue is not virtue; it’s obedience. And that’s precisely what Vermeule promotes. The moral foundation of his common-good politics will be found in statist virtues (e.g., selflessness, duty, self-sacrifice, and submission) that are anathema to America’s classical-liberal tradition. The politics of the “common good” requires citizens to selflessly sacrifice their “pursuit of happiness” in order to obey the diktat of the ruling class. True morality is not, however, about obedience, submission, and subordination. That is the morality of serfs, not of free men and women.

True moral virtue begins with a free, rational judgment of what is right and wrong and then acting on that judgment. It is about choosing to do the right thing and then doing it. Common-good morality is for the weak and lazy; it is for those who want to be told by Harvard social planners how, when, and where to be good and just. The moral hazard created by common-good legislation is that it disincentivizes people from being productive and good. It robs them of moral, political, and economic self-reliance and forces them to submit and obey. Common-good politics also incentivizes and elevates power lusters such as Vermeule, who want everyone to live by their standards and rules.

What Vermeule is promoting is a morality of nags and scolds. In its least worst form, common-good politics means right-wing “Karenism.” In its worst form, it means Islamic moral police beating women with sticks for not being veiled or burying them up to their waists and then stoning them to death. No morally decent person could support such a philosophy.

My vision of the “common good” is one where the State leaves law-abiding men and women alone to quietly build families, to work and create, to gain knowledge, to travel, to coach little league soccer, to tend gardens, to go to the local pub for a pint, to celebrate Independence Day with friends and family, to watch Clemson beat ‘Bama, and to pursue their vision of the good life. Surely this is what a philosophy of Americanism is all about.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Liberalism Is the Politics of Fear.

More than abstraction is at stake.

"Real Originalism has never been tried..."

In its effects, it is synonymous with liberalism.

A jurisprudence for all seasons—especially ours.