Digital conditions, not competing intellectuals, will make it so.

“First to the Camps”: An Interpretation of Adrian Vermeule

Liberalism Is the Politics of Fear.

When Adrian Vermeule’s “Beyond Originalism” appeared in The Atlantic, last month, it did not have to wait to be read to be condemned.

A Harvard professor of constitutional law, Vermeule has earned a reputation that extends far beyond the hallways of the legal academy, thanks largely to a provocative online personality that seems to promise—or threaten—that a Catholic integralist future for the United States is soon to arrive. Most Americans will be surprised to hear this, not least because they have never even heard the word “integralism” before, and have no idea what the fellow could be talking about.

Many people have noticed of course that the Left, that is to say, the liberals of our present regime, which is also called liberal, have become decidedly illiberal of late. The decades of pleading for the freedom “to do as one likes,” to “live and let live,” for “tolerance,” have culminated in a new juridical age committed to “punishing the wicked,” to shaming the politically incorrect, and to cancelling the insufficiently woke. As I write these sentences describing our age, it occurs to me that liberalism’s illiberal turn is so complete that it has already become a cliché.

Vermeule sees the clichés for what they are. The Left made rhetorical appeals to classic American ideas of (negative) freedom and individualism, so long as it was at the disadvantage. Once it gained firm control of cultural and governmental institutions, and won some key decisions before the Supreme Court, it abandoned the subterfuge in favor of coercion.

Since liberalism is a sham, why should the conservative, or at least the anti-liberal, not also flirt with a politics of force? All one needs is a few phrases snatched from the works of the German juridical philosopher (and sometime Nazi) Carl Schmitt, and one has assumed an ominous, eccentric, and provocative position among the intellectuals of our superficial, dilapidated, and highly partisan public square.

That, in brief, is Vermeule’s humor. When a meeting of “principled conservatives” was announced recently, he put their pictures on the internet with the caption “First to the Camps.” We are not a bright people; if I am the first to inform you of that, I apologize. Commentators on the Left denounced Vermeule as threatening to send those depicted to, they presumed, a right-wing concentration camp. The meaning of the jest was, of course, that the “principled” conservatives were making a limp-wristed resistance to mounting leftist aggression and would be rewarded for their temperance by being the first to be sent to Maoist reeducation camps…on, I suppose, President Bernie Sanders’s first day in office.

With such a reputation for provocations, Vermeule perhaps should not be the recipient of sober assessments and critique. Does it not make more sense to treat his début in The Atlantic as simply the taking of his performance into the mainstream? Has he perhaps just sought a better street corner, where, upon hearing his bark, the gauche and the earnest liberals of respectable America can recoil with expressions of righteous indignation?

Possibly. But Vermeule stages an interesting argument in “Beyond Originalism”—one that is worth considering as we chart the possibility of our present liberalism-in-decline being transformed into something else, perhaps something better.

Exposing the Liberal Fraud

Vermeule’s argument begins with an almost preposterous premise. Constitutional “originalism” has “served legal conservatives well in” a “hostile” legal environment, but that environment has now shifted decidedly in conservatives’ favor. While this is an almost laughable reading of the state of our jurisprudence, not to mention the broader culture, Vermeule proceeds with a blithe smile to propose that the time has come for something more “robust”: a “substantively conservative” vision that looks not back to the original meaning of the Constitution, but forward to the goods—the ends—at which political life aims. He calls it “common good conservatism.”

On his retelling, advocates of the constitutional theories of “legal liberalism or libertarianism” seek to “maximize individual autonomy” and “minimize” the abuse of government power. They do so by claiming to be agnostic about what is good. Liberalism aims at freedom and equality, not because these things are good in themselves, but because, when every individual has freedom and equality in the liberal understanding of these notions, every individual can decide what is the good for himself.

This, asserts Vermeule, has ever been both incoherent and fraudulent. Incoherent, because the state seeks to maximize autonomy specifically by the exercise of its power. It forces people to be free, sometimes against their will, and free in just those ways the state approves. That incoherence arises from its fraud: while claiming to be neutral regarding what is genuinely good, the state comes to treat specific understandings—and not others—of freedom and equality as substantive goods.

Behind all this, liberalism stands convicted of still another fraud. It proposes merely to clear a space where it may then leave individuals free to engage in rational discussion about what is good. The state remains silent so that citizens may speak. But, as we see from recent American legal history, liberal regimes increasingly impose elite decisions and new norms on society with the force of law and an ever-increasing contempt for the use of reason.

Vermeule quotes the Kennedy decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). He might well have followed up with the later Kennedy decision of Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). In both of these, we find a justice waxing poetic in so idiosyncratic a fashion as to have dropped even the patina of rational argument. Kennedy, Vermeule suggests, has merely revealed in his foolish verbosity what was always the case.

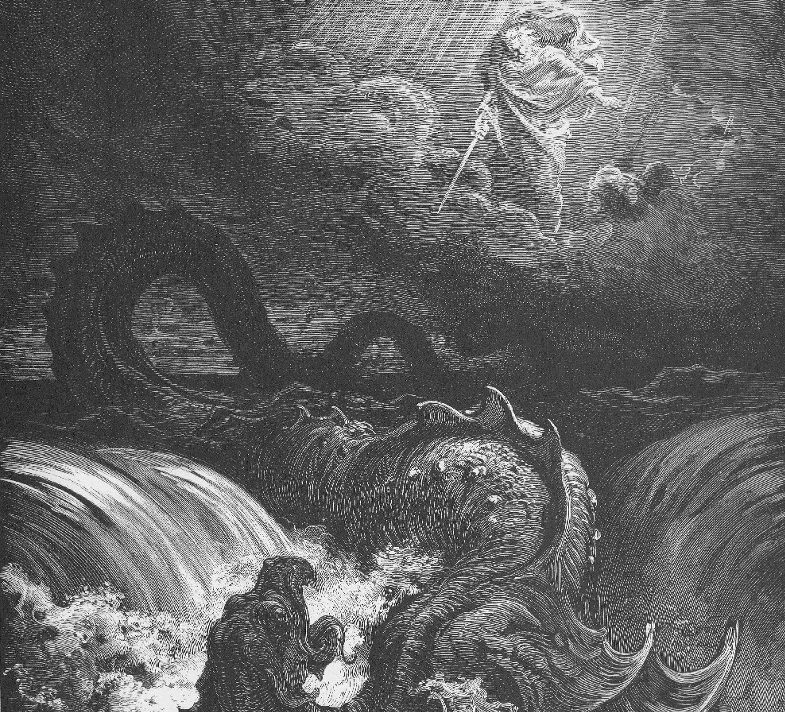

Our liberal regime was never a neutral arbiter, defending a free political realm while remaining itself agnostic about the good. It had always at its heart the state’s arbitrary imposition of its will. Liberalism, he has proven, never had freedom as its aim and limit. Liberalism, like every other political arrangement, has for its foundation nothing other than sovereignty. And sovereignty, as Carl Schmitt argues in Political Theology (1922), means to be “the one who decides in the exception.”

Liberalism has not lost its way, all this suggests. Liberalism’s way is a delusion. The state is whatever entity is sovereign, and the sovereign is whatever entity—in the end, as it were—can decide every political question. The political realm is not a place of rational discussion, but the locus of the power to decide what shall be the law, who shall be our friend, and who our enemy, and on what terms (the subject of Schmitt’s 1932 Concept of the Political).

Because our politics has been an act of power and decision all along, whatever the pretenses to the contrary, Vermeule proposes his common good conservatism to be one that accepts that definition and seeks to act to establish a strong and substantial common good. The law will play its proper, parental role in forming citizens to the good. It will promote a “substantive vision” of the good—one that does not rest content with such necessary but low goods as “health and safety” but also pursues social order, solidarity, and subsidiarity.

These last words derive from Catholic social doctrine. This doctrine first emerged within the Church, at the end of the 19th century, in response to the social problems created by modern capitalism and the political and religious problems created by modern liberalism. It was, almost from the beginning, intended to be the now apolitical (powerless) Church’s counsel to the secular, liberal powers then remaking Europe.

Vermeule holds out to us this teaching, not as religious counsel to benefit a separate liberal order, but as the substantial goods to be pursued in a new political order that has overcome the old hang-ups, limitations, and charades of liberalism.

Three Premises: Descriptive, Normative, and Prospective

“Beyond Originalism” as a whole makes three major claims: one descriptive, one normative, and one prospective.

As a description of how liberalism has worked, or presently operates in our age, it seems convincing outright. The new moral order being foisted upon us, of which Kennedy’s decisions are clownish exemplars, is one of naked force; Kennedy’s decisions, with their flighty prose, flaunt an absolute contempt for reason.

On the ground, as it were, our moral debates consist largely of the denial that there is a natural order, corrupted by sin but still intelligible to the rational mind. Natural law is brushed aside as an ideology; moral claims are ignored, because all is relative; arguments about the truth are judged undecidable by reason…except, of course, where the law, morality, and truth can all—without argument—be seen to “bend toward justice,” which means, by liberal lights, toward an antinomian therapeutic individualism. It is the coercion of the state (and its effect, of which, more anon), not the reasoning of self-governing citizens, that does the bending.

Such is his description of our present order, which the conservatives in Vermeule’s audience will agree has been very much corrupted indeed and which they had sought to mend by way of originalism. But, we ask, is this description in fact normative in regard to the political as such?

Power Politics is Not Enough

When Schmitt offered his hypothesis, it was in the effort to awaken the procedural liberalism of the Weimar Republic to the dangers posed by the rise of the Nazi party. The German government’s impotence in the face of an opponent that proposed to liquidate the state struck Schmitt as both dangerous and absurd. When threatened, the sovereign must decide; Weimar should have suspended its own laws and banned the Nazi party from participation in elections.

Schmitt was a complicated and troubling figure, even to those Catholic intellectuals of his day who studied his work with admiration. When Hitler rose to power in 1933, Schmitt joined the Nazis and did so primarily because the Nazis had shown they understood the nature of the political. Power lay at its base and everything above it was of incidental or secondary importance.

This is not how the Anglo-American constitutional tradition understands things, of course. Nor is it what any political philosophy founded on the classical vision of Aristotle could propose. Power is present in every regime, but we can tell the difference between a good regime and a bad regime by how it wields that power. Politics is precisely the place for the discernment of justice and injustice, good and evil, to guide the practice of power by the regime.

On this score, Schmitt—and Vermeule, to the extent that he borrows from Schmitt—is too superficial. Constitutional theories—liberal, originalist, or otherwise—are not merely posterior rationalizations of power-decisions, as he assumes. They are arguments about the goods at which society aims—for which power is necessary, but as an adjunct. To fetishize power, or to pretend it is the last or only foundation of politics, is to render political life simpler than it really is.

Consider, for a moment, Shakespeare’s King Lear. The play poses the question to us, does a king’s title lie in his authority—his moral right—or in his power? And its final answer is, “yes.” Lear retains his crown but surrenders his power; in the course of a few weeks he is humiliated and brought to madness and despair; the kingdom falls into civil war and suffers foreign invasion. Power seems to be everything.

But, in the end, order is restored, in a manner of speaking, not through martial victory, but through the death of Lear’s innocent daughter, Cordelia. Her embodiment of truth and love—she refuses to speak a lie, and she knows that she has been brought low out of self-sacrificing devotion to her father—possesses an authority to which power, finally, bows. It would seem, therefore, that Vermeule’s reduction of the political to sovereignty is not normative.

Yes, conservative originalists would likely abandon originalism if, for instance, it did not help to overturn Roe v. Wade (1973). Vermeule takes this as evidence that they were not in earnest: it was not their theory but the decision, the result, that matters to them. But could it not rather be the case that just political procedures will be intrinsically connected to substantially just ends? The form of the system, like the forms of all things, is designed with the good end in view.

Prospects for a Renewed Classical Politics

Vermeule has so well prepared his readers to be shocked by his account of liberalism, politics, and power, that his most cogent premise risks going overlooked: his proposition that politics be reordered to the good. Law and the state must order our common life to the common good. As others have observed, if one says, “the government must lead us to freedom,” right-thinking liberal society nods in vociferous agreement. But if one deletes the word freedom and inserts any other substantive noun—truth, for instance, or virtue, or holiness—those same persons recoil in horror.

When Thomas Hobbes published his Leviathan (1651), the reaction seems to have been not much different from that which greeted the appearance of Machiavelli’s Prince in England (1585), to wit, disgust and horror. Whatever the wayward sinfulness of man, the political order was understood to be roughly what Aristotle had said it was 2,000 years before: a natural arrangement of social animals, under legitimate rulers, aimed at the common good. That the ruler should seek chiefly to maintain his own rule, as Machiavelli indicated, caused dismay; but what was so shocking about Hobbes?

For Hobbes, this classical idea of the state aiming at the “common good” was no strong foundation for social life. Depending on the person, almost anything can appear to be good at some point; goodness is relative, subjective, fickle, and unstable. Furthermore, there is no summum bonum, no highest good at which all persons unanimously aim as the end—the purpose—of their life.

We merely flit from desire to desire and try to keep alive as long as we can. We cling to life and seek to extend it, despite its increasing pettiness and vacuity. The radical decentralization of religious authority catalyzed by Luther and the printing press exacerbated this problem, making it imperative to find some way of vesting legitimate and final authority in a both spiritual and temporal ruler.

Fear, however, was a different story than desire for Hobbes. We can only desire what we have some knowledge of, but we can fear everything, including that which we do not know precisely because it is unknown. Fear of evil is no less relative and shifting than a love of the good, Hobbes concedes, but fear dwarfs desire quantitatively. There is just so much more to be afraid of in the world than there is to love.

And so, Hobbes conceived an account of politics rooted entirely in fear. If you fear death at the hands of other persons, he tells us, then I have a plan for you: lay down your unfettered right to do anything, including taking your enemy’s life, in the interest of forming a covenant with those enemies under a sovereign, who will protect your life against them, and their life against yours.

Hobbes does not claim that life is good, only that most of us fear the unknown that is death. Not everyone fears death, but most of us do, and so it is a firmer, more widespread basis for political life than goodness could be (made firmer still when we kill off those who do not fear death). The sovereign is whoever can protect us from death at the hands of others the best and the longest; and so, the politics of fear is also fundamentally a politics of power.

Liberalism writ large was corrupt from the beginning. It proposed to be a regime of discussion, a place of rational debate made possible by securing the relative goods of freedom and equality, but in fact freedom and equality were just inducements to make it more likely that those who fear death will entrust themselves to the covenant protected by the sovereign’s power. It was a pretend kind of freedom. Decision was all.

In liberalism, fear and power bear an intrinsic relation to one another. Vermeule perceptively exposes liberalism’s vision of power, but then accepts it as normative. Meanwhile, he rejects its foundation in fear, and seeks to restore an older and worthier politics rooted in, because it aims at, the good. And so, paradoxically perhaps, his common good constitutionalism is classical in substance but “liberal” in procedure. The shock of his argument, however, lies in his insisting that the procedures—the rules of the game—of liberalism are not what most of its defenders take them to be. In practice, liberalism means decision, not discussion.

Liberalism is a political regime of fear. And, as Vermeule proposes, the law helps to form its subjects. The last hundred years or so have revealed that liberal societies render their citizens increasingly agnostic about the good and skeptical that reason can arrive at a knowledge of it. Political life then comes to concern itself exclusively with warding off various “evils,” by which is meant not things that are substantively evil (because, as Hobbes showed us, “evil” is no less subjective than “goodness”), but things that we are capable of fearing.

Among the things this regime trains us to fear are those who propose the good to us—people like Adrian Vermeule.

Four centuries ago, Hobbes’s politics of fear seemed unthinkable. Now, most people can think of politics in no other terms. I suspect that Vermeule’s humor is intended to awaken us to how unhuman, indeed anti-human, a politics rooted in fear clearly is. If politics remains a mere defense against what we fear, our lives remain nonetheless defined—and made or marred—by our pursuit of our purpose, our honest good. Politics not only ceases to serve its proper good, but contradicts ours.

The sooner we recognize the political realm as a place where that good can be discovered, understood, and pursued in common, the sooner we will recover a good without which we can perhaps stay alive but may never truly live. I do not know if Vermeule is serious about all this, but I think we should be.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

More than abstraction is at stake.

"Real Originalism has never been tried..."

In its effects, it is synonymous with liberalism.

A jurisprudence for all seasons—especially ours.

Only a dark theology can baptize the administrative state.