Democracy and despotism in a digital age.

What Sean Wilentz Gets Wrong About Sen. Tom Cotton and the American Founding

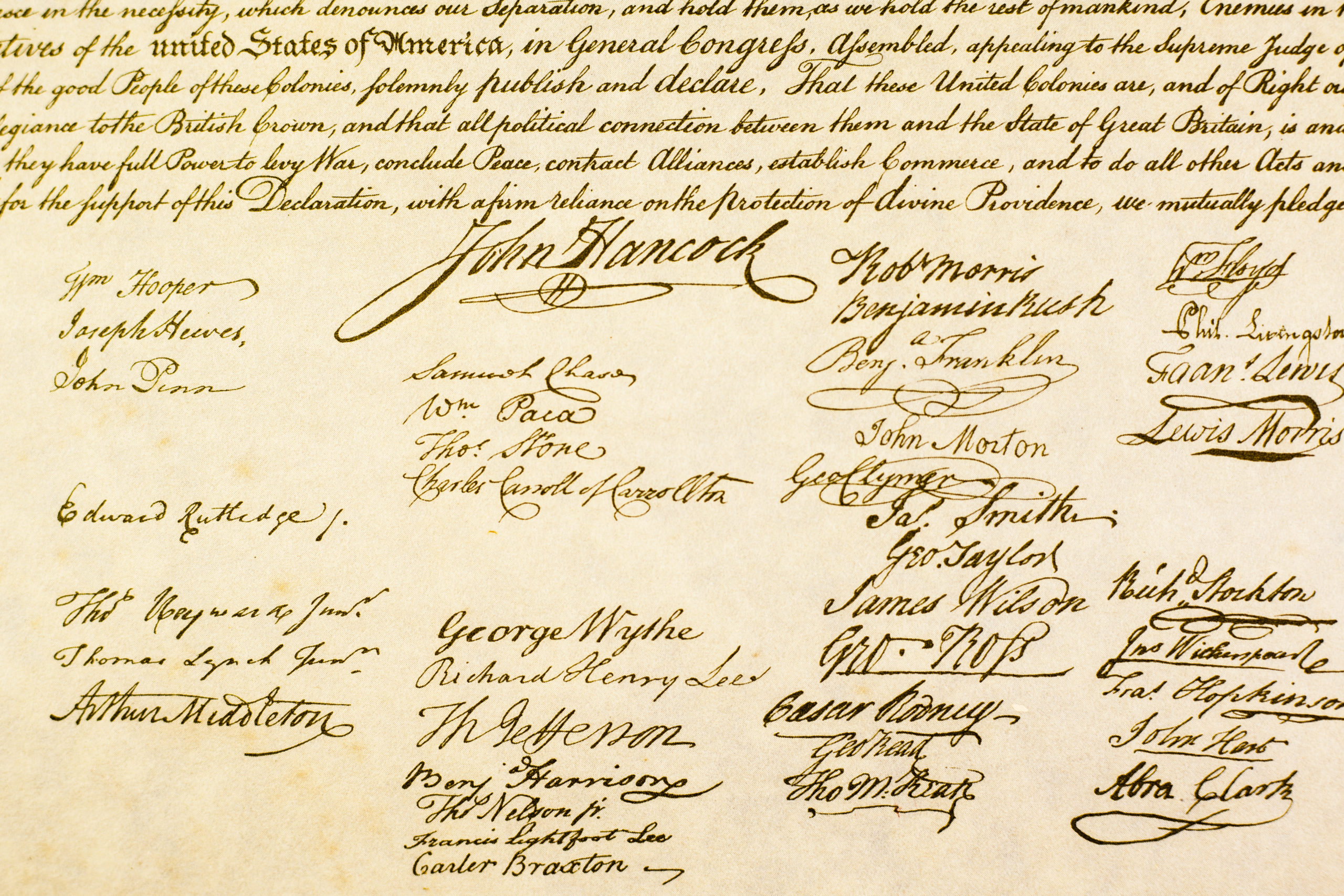

Princeton historian Sean Wilentz recently criticized Sen. Tom Cotton for claiming that the American founders considered slavery “the necessary evil upon which the union was built.” Wilentz thought it suggested that Americans needed slavery in order to create the United States. Sen. Cotton also said that “the union was built in a way, as Lincoln said, to put slavery on the course to its ultimate extinction,” which implied, in Wilentz’s mind, that slavery was destined to be abolished. While the senator could have articulated the Founders’ compromise with slavery more clearly, his view that they tolerated slavery for the sake of unifying the American states and framed a constitution to eliminate slavery in the long run is correct.

Wilentz rightly noted that no one at the constitutional convention actually called slavery a “necessary evil.” But Sen. Cotton’s point was not that the founders believed slavery was a necessary ingredient for creating self-government, an absurd claim on its face. Rather, as Cotton later explained, “The Union and the Constitution were necessary to put slavery on the path to ultimate extinction.” In other words, they thought “a more perfect union” of the American states would best secure freedom for all in due time. Slavery was an evil they tolerated in the midst of fighting to secure their independence from Great Britain, a fight they believed they could not win if they attempted to free themselves and their slaves at the same time.

Wilentz concedes that the framers believed slavery was evil, adding that a “great majority” sought to exclude it from the new federal government’s protection. He even admits that a delegate to the constitutional convention (Charles Cotesworth Pinckney) argued that slavery was necessary for the survival of “the Carolina economy,” but adds that his opinion was flatly rejected. However, the delegates did not deny the economic significance of slavery to the deep South, only Pinckney’s desire for slavery to be explicitly protected in the federal constitution.

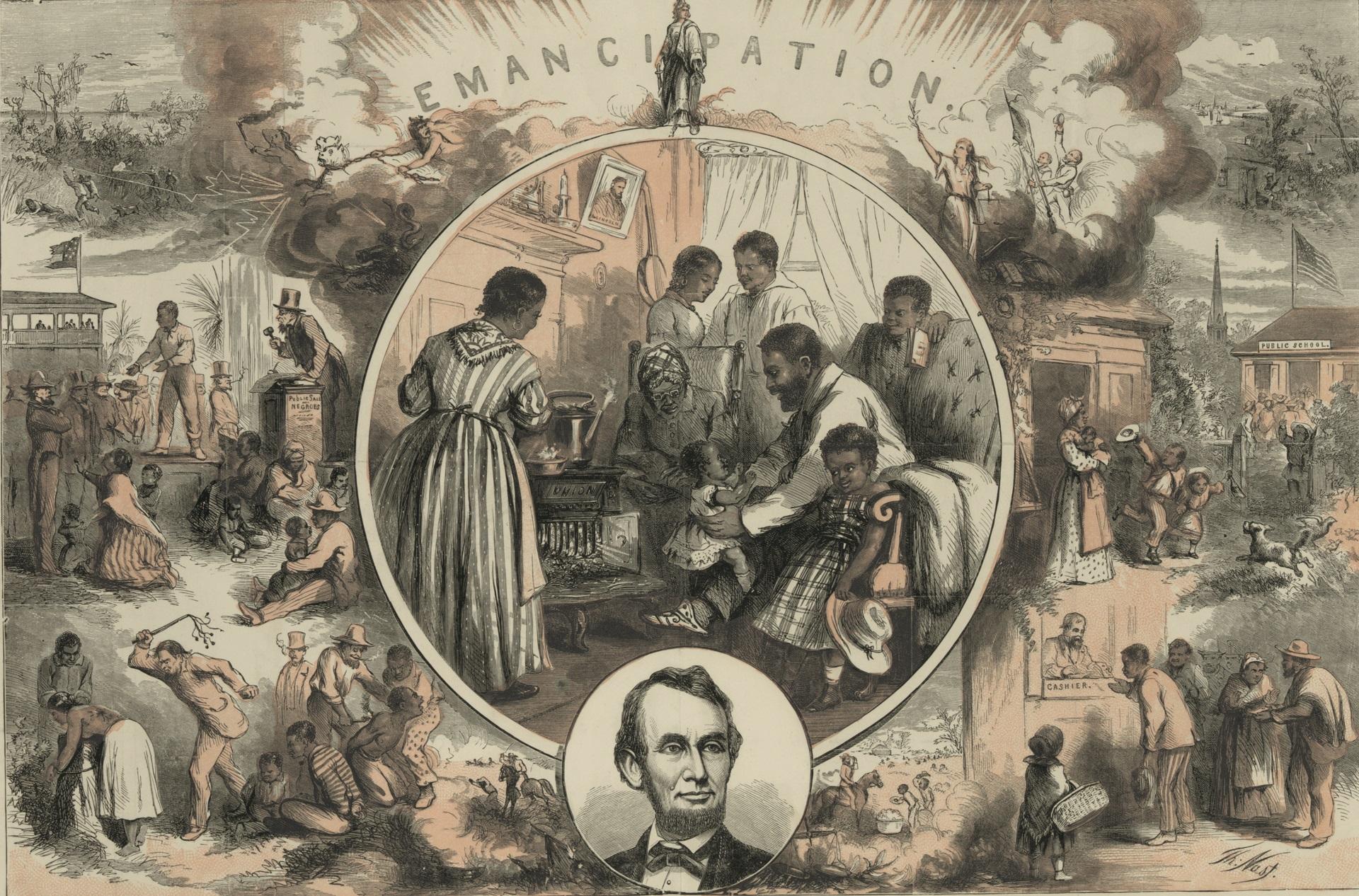

As proof that the Constitution “was hardly an antislavery document,” Wilentz mentions that “the lower South slaveholders managed to win compromises that offered some protection to slavery in the states.” But he later insists that “the Constitution contained powerful antislavery potential.” He cites Congress’ authority “to regulate or ban slavery in areas under its purview, notably the national territories,” from which future states would arise. Moreover, like Sen. Cotton, Wilentz cited Lincoln to support the view that the 1787 Northwest Ordinance indicated a founding animus against the spread of slavery. Both the Constitution and early federal laws preventing slave importation (1808) and slavery’s expansion into the Northwest Territory (in 1787 under the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union and 1789 under the U.S. Constitution) indicated that while the founding generation could not abolish slavery immediately, they intended to restrict it to the original states. This would reduce its supply and forestall its expansion and further entrenchment on American soil.

Curiously, Wilentz brings John C. Calhoun into the conversation as a critic of congressional regulation of slavery, but he omits mentioning Calhoun’s infamous observation about the peculiar institution: “where two races of different origin . . . are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good–a positive good.” The godfather of secession and southern independence deliberately employed “positive good” to counter the conventional view of his day—namely, that racial slavery was a “necessary evil.” That phrase was not invented by Sen. Cotton, but used in the early 19th century to describe the traditional American attitude towards slavery, but one that Calhoun rejected.

For some reason, Wilentz affirms that “Lincoln’s and the antislavery Republicans’ concerted political efforts” helped “vindicate the Constitution’s antislavery elements,” but denies Sen. Cotton’s appeal to Lincoln as a defender of a constitution designed “to put slavery on the course to its ultimate extinction.” Wilentz tries to balance the pro-slavery and pro-liberty aspects of the Constitution, but still concludes that the framers “gave the federal government the power to restrict its growth—and so hasten its demise.” How does this differ from Cotton’s opinion that the constitutional union “was built in a way, as Lincoln said, to put slavery on the course to its ultimate extinction”?

To write that Sen. Cotton “appears unaware of how profoundly the Constitution of the United States of America differed from that of the Confederate States of America” is to ignore the senator’s appreciation of Lincoln as an antislavery constitutionalist. Wilentz’s attempt to characterize Sen. Cotton as somehow pro-slavery in his reading of the constitutional framers is simply a partisan swipe masquerading as academic scolding.

In the end, Sen. Cotton was only guilty of being an old school Republican, one who looks to Lincoln as the gold standard for applying the founders’ principles to today’s political problems. It’s no secret that Prof. Wilentz ran afoul of fellow historians and public intellectuals for criticizing the 1619 Project and defending an interpretation of the founding that sees more good than bad in its achievements. The question is, in the year of the “1619 riots,” does the professor side with a senator who appreciates what the founders achieved on behalf of equality and liberty, or does he now find more to condemn than praise in the American founding? If there ever was a time that Americans needed to take sides on this question, this is it.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Revisionist Black supremacist history can't grasp our shared equality.

There is nothing manly in throwing up your hands.

They are as clueless as the ancien régime.