Democracy and despotism in a digital age.

America Wasn’t Founded on White Supremacy

Revisionist Black supremacist history can't grasp our shared equality.

When Beto O’Rourke’s poll numbers were cratering in the Democratic primary runoff this summer, he decided that the only decent thing to do from his perch of white privilege was to confess that “this country was founded on white supremacy.” This did little to boost his national appeal. Nevertheless, the New York Times Magazine and the Pulitzer Center have doubled down on the claim that white supremacy is the essence of the American regime in their “1619 Project.” Complete with study guides and curricula which supplement more than thirty essays and artistic productions, this multilayered initiative seeks “to reframe the country’s history” by “placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.”

One crucial “1619” installment is a 7,300-word essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones titled “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals were False When They Were Written. Black Americans have Fought to Make Them True.” In Hannah-Jones’s version of American history, the Declaration of Independence marks not the beginning of a new era in human civilization, but only the continuation of white supremacy’s oppressive march on American soil. America did not begin in 1776 with the declaration that “all men are created equal,” but with the clear negation of that statement in 1619, when the first 20 American slaves landed in Jamestown, Virginia. As far as the bedrock of America goes, it’s racism all the way down.

Hannah-Jones ably informs us of many important contributions that blacks have made to America’s political and cultural prosperity. But she unfortunately excludes significant facts that would ruin her disingenuous argument about the American Founders and their most exemplary defender, Abraham Lincoln.

Hannah-Jones’s mistake is to interpret American history as a zero-sum narrative, wherein the recovered strivings of black folk must displace the recorded achievements of white folk. What we need is a more capacious revision of American history—one that incorporates the heroic participation and fealty of black Americans while also acknowledging the Founders’ efforts to establish a free society in a land accustomed to racial slavery. Instead, Hannah-Jones’s “history” is riddled with half-truths, overstatements, out-of-context quotations, and just plain falsehoods about the founding and Lincoln. She distorts our past and undermines our common understanding of how we strove as a diverse people to align our practices with our noblest professions.

The strangest thing about the essay is the claim that transplanted Africans and their descendants were the key to American greatness. Hannah-Jones cites no African principles of self-government or ideals of humanity when she quotes the famous pronouncements of the Declaration of Independence. She merely asserts that “black Americans, as much as those men cast in alabaster in the nation’s capital, are this nation’s true ‘founding fathers.’”

Ironically, however, even in this warped retelling, black Americans’ principal means of saving white Americans from their worst selves was not anything African but the quintessentially American ideals of human equality and natural rights. For example, Hannah-Jones lambasts “Jefferson’s fellow white colonists” for establishing “a network of laws and customs” in order to perpetuate slavery. But she omits the fact that between 1781 and 1783, Massachusetts abolished slavery when slaves sued for their freedom on the basis of the state’s own constitution. That document asserts in its Declaration of Rights that “all men are born free and equal.” Do the courts of Massachusetts, relying upon the Massachusetts Constitution, count as part of that “network of laws and customs”? Massachusetts was one of several American colonies, including Virginia, that attempted to prevent the importation of slaves only to see those efforts rebuffed by Great Britain. King George III’s 1770 veto of American bans on slave importation made it considerably more difficult for colonists to wean themselves off of the peculiar institution. Jefferson actually included this accusation against the king in his original draft of the Declaration of Independence. The charge was only deleted by the Second Continental Congress because it did not apply to every American colony.

Despite this evidence of colonial resistance to slavery, Hannah-Jones somehow maintains that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” Of course, there’s not a word about that in the Declaration of Independence. Nor can she explain why six of the original thirteen American states abolished slavery in the decade and a half after the 1783 Treaty of Paris formally ended the war for American independence. Purely because slavery was not immediately abolished upon the war’s end, Hannah-Jones concludes that “slavocracy” better describes the American founding than “democracy.”

The Wisdom of the Founding

Had Hannah-Jones read almost any of the writings on slavery by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, or James Madison (not to mention Ben Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, James Wilson, or John Jay), she would have learned that the Founders not only acknowledged the injustice of the institution, but also discussed impediments to emancipation in the near term. Though these men were revolutionaries, prudence marked their efforts to establish national independence: they believed they could not free themselves and their slaves at the same time. To insist on the latter as a condition of the former would have doomed both imperatives. For example, South Carolina and Georgia were land rich and labor poor, and this made them hesitant to stem the flow of slaves into their states. To lose their support during the Revolutionary War, when only a united effort promised any hope of success, would have made outlandish an already daunting military enterprise.

But if the Declaration of Independence cannot be trusted to represent the true intentions of the Founders, Hannah-Jones does no better at interpreting the U.S. Constitution. We learn that “the framers carefully constructed a document that preserved and protected slavery without ever using the word.” But she ignores the debates of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Madison’s detailed records of those proceedings show that he “thought it wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.” He and the rest of the Framers kept the word slavery out of the Constitution because they envisioned a day when slavery would no longer exist on American soil.

What about Article 1 Section 9, which prevents Congress from banning the importation of slaves for twenty years? Hannah-Jones sees in this only the perpetuation of slavery, but she misses the growing national impetus against this nefarious commerce. Had there been no such impetus, there would have been no need to delay Congress’ attempts to regulate it. As Madison observed in Federalist 42: “It ought to be considered as a great point gained in favor of humanity, that a period of twenty years may terminate forever, within these States, a traffic which has long and so loudly upbraided the barbarism of modern policy.”

Reading Hannah-Jones, one would never know that Madison had anything to do with the Constitution, let alone that he and other Framers were at pains to document their anti-slavery intent. She claims that “the white men who drafted those words did not believe them to be true for the hundreds of thousands of black people in their midst.” This reflects a woeful ignorance of the writings of key Founders. The question was never whether the enslaved deserved their freedom; it was how to secure their rights in a peaceable, lawful fashion.

The slaveholding Founders were all too aware that slaves had legitimate grievances. As Jefferson put it in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), “ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained…will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions, which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.” Jefferson admitted that “deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites” further complicated any attempt to free blacks in a way that would enable them to enjoy their natural rights. He thought that emancipation would need to be followed by expatriation, i.e., colonization, in order to assuage the fears of the white population. Writing John Adams during the Missouri crisis of 1821, Jefferson feared that to emancipate slaves with no consideration of the social repercussions would be giving them “freedom and a dagger.” This was speculation on his part, but not unfounded, as the Gabriel Prosser revolt in Virginia and the Haitian revolution led by Toussaint Louverture illustrated the potential for a race war wherever slaves outnumbered the white population. America’s most famous and perceptive foreign observer, Alexis de Tocqueville, predicted as much.

To complete her assault on the Founders, Hannah-Jones must take down their greatest defender, Abraham Lincoln. She claims that Lincoln “believed that free black people were a ‘troublesome presence’ incompatible with a democracy intended only for white people.” She neglects to mention that Lincoln was describing Kentucky senator and slaveholder Henry Clay’s opinion regarding the difficulty of free and enslaved blacks living in the same community. Lincoln was delivering a eulogy for Clay in 1852, at which point agitation over slavery was so intense that the prospects for peaceful, lawful abolition looked increasingly distant. Clay had encouraged free blacks to establish a self-governing colony in Africa. These efforts met with Lincoln’s approval because he thought they could help ease the mounting tensions in America and perhaps facilitate the eventual emancipation of all enslaved blacks on American soil.

Hannah-Jones compounds her error when she quotes Lincoln’s direct and bracing speech to black leaders in August 1862. The president did tell his listeners that “your race suffer very greatly, many of them, by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence.” He encouraged them to consider the prospects of colonization. But in doing so, Lincoln was preparing a nation at war with itself for a proclamation of emancipation in rebel-held states. The president needed to show the country that all avenues for resolving the conflict were being pursued before he resorted to abolition by executive fiat.

Hannah-Jones acknowledges that Lincoln was concerned about the proclamation’s reception by white Americans. But then she asserts that Lincoln “also opposed black equality,” quoting a comment he made during his 1858 debates with Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas. This quote is completely and misleadingly decontextualized. Lincoln was responding to Douglas, who declared in their first formal debate that “I am opposed to negro citizenship in any and every form. I believe this government…was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever.”

Lincoln had to challenge Douglas’s unabashed white supremacy in a state where blacks could not vote, serve in the militia, or sit on juries if a white person was a defendant. Abolitionists were viewed as radical extremists, indifferent towards the Constitution and the rule of law. So Douglas did everything he could to tar Lincoln and the Republican Party with the abolition brush. Hannah-Jones does quote Lincoln accurately: he said that he did not favor making black Illinoisans “politically and socially our equals.” But she fails to appreciate that Lincoln had to respond in a manner that could appeal to moderate elements of a state where white supremacy was the norm and not the exception.

If Lincoln played the race card, then Douglas played the whole deck. But what is actually remarkable is the degree to which Lincoln defended the natural rights of black people. Where Douglas interpreted the Declaration of Independence as having no application to blacks, Lincoln begged to differ: “There is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence—the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Lincoln did concede some level of inequality between whites and blacks, but only as part of his effort to move his audience gradually away from their bigotry and toward a more enlightened view. “I agree with Judge Douglas he [‘the negro’] is not my equal in many respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment,” said Lincoln. “But,” he hastened to add, “in the right to eat the bread, without leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man.”

Contrast the unapologetic white supremacy of Douglas with Lincoln’s efforts to inform and elevate public opinion. White Illinoisans at the time did not even allow blacks to move to their state. Lincoln therefore could not even begin to discuss granting them civil or political rights. Instead, he reminded his white audience of their own rights, grounded in nature and enumerated in the Declaration of Independence. He then had the courage in an election year to insist that these were the same rights that black people possess as well.

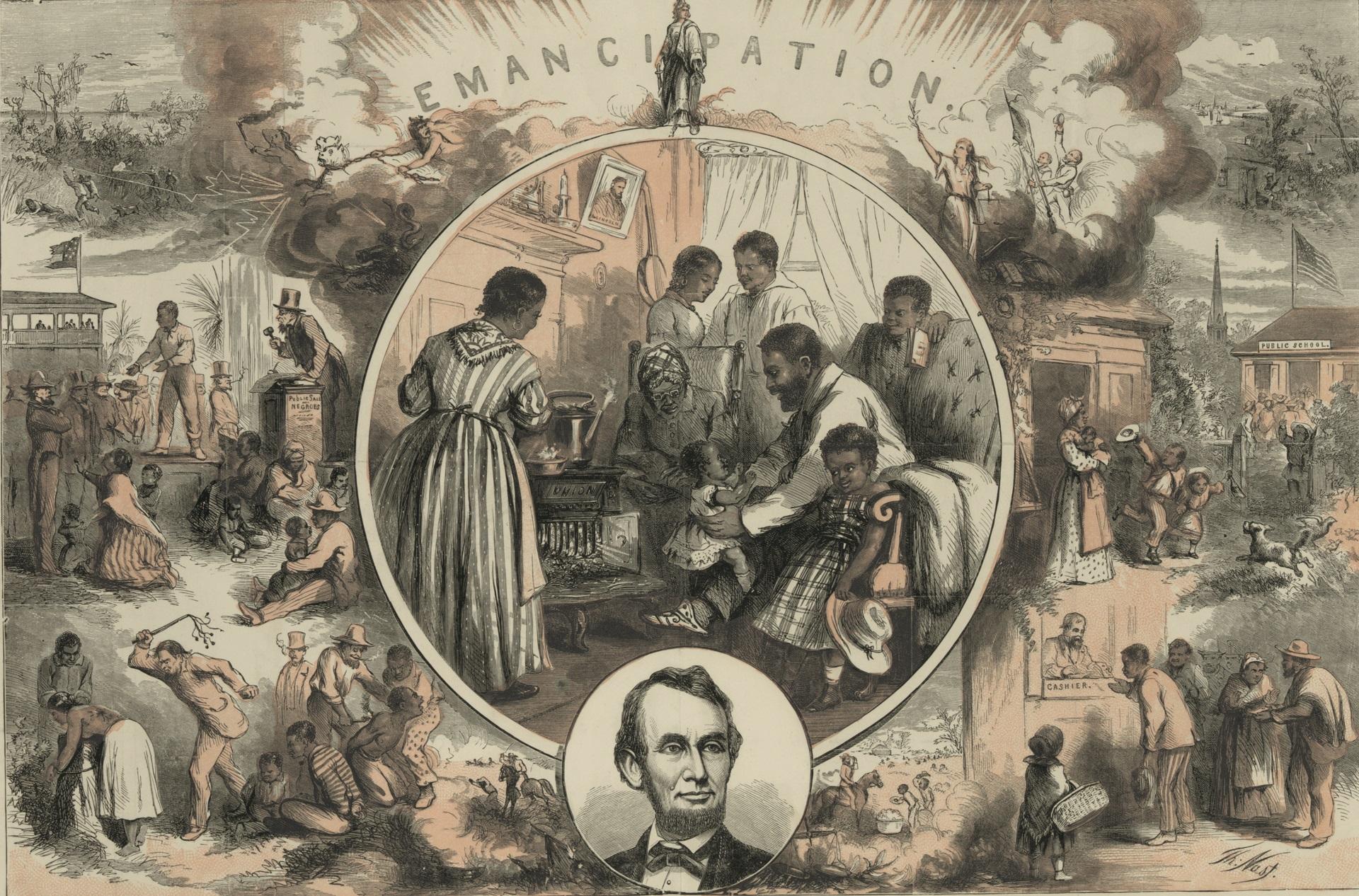

When Hannah-Jones asserts that “anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country,” citing Lincoln’s presidency as yet another example of how this played out poorly for blacks in American history, she gives no credit to the president who did the most to “preserve, protect, and defend”—even to the point of war—the Constitution and the kind of country that could secure the rights of racial minorities. There’s no mention of Lincoln’s vigorous invective against the 1857 Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, wherein he lambasted Chief Justice Roger Taney for reading black people out of the Declaration of Independence. There’s no mention of the Gettysburg Address in 1863, which challenged the nation to experience “a new birth of freedom” that would include 3-4 million blacks as fellow citizens. There’s no mention of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, in which he speculated that the devastating Civil War may have been America’s punishment from God for the profound wrong done to her black inhabitants. There’s no mention that Lincoln was assassinated because he encouraged states to support education and voting rights for black people. For this reason, Frederick Douglass gave an 1876 speech in which he called Lincoln “the first martyr President of the United States.”

But for Lincoln, whose words and deeds remain the gold standard for American rhetoric and policy, the United States would have quickly veered from the country that the founders set into motion. What Hannah-Jones describes as “racist ideology that Jefferson and the Framers had used at the nation’s founding,” Lincoln described (in an 1859 letter to Republican congressman Henry L. Pierce) as “the definitions and axioms of free society.” Lincoln understood the predicament of the Founders, men who strove not only to establish liberty but to establish a regime that could last long enough to secure it. In his seventh and final debate with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln observed, “We had slaves among us, we could not get our Constitution unless we permitted them to remain in slavery, we could not secure the good we did secure if we grasped for more; and having by necessity submitted to that much, it does not destroy the principle that is the charter of our liberties.”

Douglas’s rejoinder was the skewed doctrine of “popular sovereignty,” teaching free white northerners not to care if the enslavement of black people spread into federal territories, all in the name of “our fathers.” Lincoln rejected this characterization of the founders as neutral regarding the future of slavery in America. He considered Douglas, and not southern defenders of slavery, as “the most dangerous enemy of liberty, because the most insidious one.” Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” would teach Americans to see politics as simply the enforcement of self-interest, a matter of majority might dictating right. Lincoln had the foresight to see that for slavery to become national, northerners need not be persuaded by southerners that it was “a positive good,” as South Carolina Senator John Calhoun had taught. Simply persuade white northerners not to care what happens to folks who do not look like them, and therefore Congress should not prevent the spread of black slavery into the territories. Once that happened, Lincoln thought the nationalization of slavery would occur in short order through a second Dred Scott case, which would affirm the enslavement of blacks as a constitutional right despite any state law or constitution to the contrary.

Patriots, Black and White Together

That Hannah-Jones is oblivious to Lincoln’s efforts on behalf of blacks muddles her attempt to view American history through the lens of black patriotism. Here her argument is reminiscent of one by Ralph Ellison, who wrote in a 1970 Time magazine essay that “it is the black American who puts pressure upon the nation to live up to its ideals.” But Ellison, though aware of the early republic’s shortcomings, still called the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights “sacred documents.” This gives more credit to the Founders than Hannah-Jones does, to put it mildly. She correctly notes that “in every war this nation has waged since that first one, black Americans have fought.” But she fails to appreciate that these black soldiers were devoted to America because they understood that liberty would come from fighting for the country’s survival, not supporting its enemies. As the boxer Joe Louis once commented, “there are a lot of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain’t going to fix them.” Black patriots strove to engage the ideals and institutions of American self-government. This, of course, required an appeal to a sympathetic white majority. Hannah-Jones claims that “for the most part, black Americans fought back alone.” But this is impossible: blacks simply could not have secured their civil rights without the help of countless white Americans.

Let American history provide the lesson. If the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments had required a black majority to pass Congress, how secure would the rights of black Americans be? How much progress would the nation have made if color and not citizenship, race and not humanity, characterized the political practice of America? Surely the United States advanced on this front because the principle of equality won over more and more Americans—most of whom were white. In 1954, there were no black justices on the Supreme Court that decided Brown v. Board of Education. In 1964, there were no black senators when the Civil Rights Act was passed. Ditto for the 1965 Voting Rights Act. To assert that “anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country” is to turn a blind eye to the profound conviction of most white Americans “that all men are created equal.” Only by ignoring this conviction could Hannah-Jones deny that 1776 is the legitimate origin of the American endeavor, and that the political development of the United States has in fact been one long civil rights movement.

Channeling the muse of Ellison, Hannah-Jones writes that “to this day, black Americans, more than any other group, embrace the democratic ideals of a common good.” This will continue to hold true only if black Americans continue to learn that the American Founding was good, right, and exceptional in its principles and structures. As President Bill Clinton (echoing Dwight Eisenhower) said in his First Inaugural Address: “There is nothing wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America.” If Americans of all races learn that the Spirit of ’76 is the better angel of our political nature, and not some demon to be exorcised, then we can reclaim our common political heritage. Only then can diverse Americans have a reasonable hope for unity even as we debate the means by which we seek to secure the common good.

But if Americans lack a conviction about the essential goodness of the United States—a goodness that Hannah-Jones makes more difficult to see and understand—then what Ellison called “the mystique of race” will continue to obscure our national identity. During our greatest crisis of national identity, the American Civil War, Lincoln and many fellow Americans—black and white—did their best to preserve what was right about the Founding in the face of both misinterpretations and outright rejections of the nation’s fathers. Our generation will have to do no less.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

There is nothing manly in throwing up your hands.

They are as clueless as the ancien régime.

Today’s miseducated fame-seekers can’t lead us, unless it’s off a cliff.