Democracy and despotism in a digital age.

Our Elites Are Steering Us Towards Civil War

They are as clueless as the ancien régime.

Along with the Upper West Side of Manhattan and a few other redoubts, my suburban neighborhood near the Maryland border represents the heart of what some pundits call the “blue church.” It is increasingly a dream world.

I drop in periodically at Politics and Prose, a prominent bookstore in Northwest D.C., to browse and shop. Lately I find it more and more difficult to avoid eavesdropping on the conversations of the elderly white women (lifelong Democrats, of course) who make up 80% of the regular clientele.

Not that I try especially hard to tune out, because it is fascinating to hear what they say in their unguarded chit-chat.

No Japanese soldier on a remote Philippine island in 1947, oblivious to the emperor’s surrender, was more disconnected from the real world than these educated, well-spoken women. They read the Washington Post and listen to NPR every day, and therefore have no idea that they are imprisoned on a kind of island of the mind.

The bookstore’s regular customers, mostly retired professionals, are the kind of well-to-do urbanites that used to be called limousine liberals. But my bibliophile neighbors, with their casual shoes and canvas tote bags, generally prefer a Prius to a limo. Even so, they enjoy lives of comfortable physical ease, security, and culturally enriched leisure. One might think this would make them nice. And on many topics (grandchildren, for instance) they are.

But their conversations turn easily and often to politics—in particular, the illegitimacy of our odious president and the racist underclass that elected him—and then their tone becomes suddenly and shockingly nasty. That nastiness arises in part, no doubt, from an aversion to an uncomfortable truth: that the cozy world of these coastal urban elites is far from natural or normal. It is the product of an artificial, often dishonest patchwork of legal, political, and cultural practices that have been distinctly unfair to millions of disenfranchised Americans.

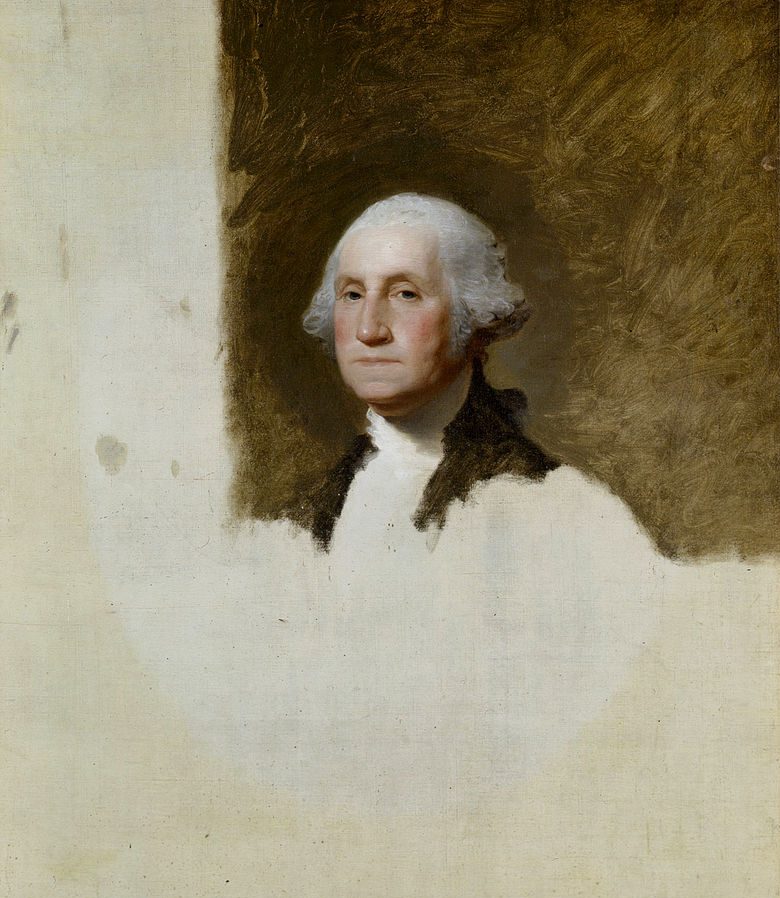

It was said of the ancien régime—the nobility that reigned prior to the French Revolution—that “they learned nothing and forgot nothing.” In his monumental book on Lincoln and the principles of self-government, A New Birth of Freedom (2000), the late Claremont professor Harry Jaffa expounds on this observation: “They could forget nothing, namely their undeserved and socially useless privileges; and they could learn nothing, namely that their fellow countrymen would no longer tolerate the continuance of their privileges.”

One might think that this world of artificial nobility is dead and gone. But in deep-blue sanctuaries like my local bookstore—that bubble of bubbles, the summa bubblica of America’s leftist oligarchy—a version of this same decayed aristocracy is still holding on.

These liberal ladies (and a few distinctly milky gentlemen) are harmless enough in one sense. They aren’t abusing the working class in any direct or obvious way—certainly not in their own minds! Unlike the French gentry, they do not dwell in ostentatious luxury while serfs labor in hunger. Even less are they complicit in anything like the gruesome brutality of chattel slavery in the Old South.

Still, they do partake in their own shallow way of an intellectual and moral presumption that is not at all harmless. Like every privileged class in history, they are convinced that they deserve what they have, however slight their own efforts may have been in the smooth glidepath of their lives.

The recognition of unearned privilege can sometimes turn psychologically sideways, with sublimated guilt erupting into destructive revolutionary fervor. Rarely, alas, does it flower into genuine humility and charity. But the complacent retirees with whom I rub elbows are not directing their unconscious guilt (if they have any) into overthrowing the system.

To the contrary, the oligarchy they represent frantically wants to preserve, or bring back, the pre-2016 uniparty establishment in which they flourished. Because they cannot comprehend that their fellow countrymen will no longer tolerate their socially useless sinecures, they retreat ever further into monasteries of self-deception.

But this cannot continue; something must give, and it seems ever likelier that the way forward will be rough.

In New Birth and other writings over the course of his long career teaching political philosophy, Jaffa explained that the American Founders solved the crisis of religious warfare (which had plagued Europe for centuries) through the separation of church and state. The power of government would no longer be used by believers who were in authority to persecute different believers who were out of authority.

Yet the danger of religious warfare can return in secular form when people no longer agree on the basic principles of republican government and regard each other as political heretics rather than fellow citizens. “Elections,” Jaffa wrote, “may properly decide only between those whose differences of opinion are not differences of principle.”

For example, in 1861 the Confederacy endorsed the idea of slavery as a “positive good.” This doctrine of “you work, I eat” replaced the equal natural rights doctrine of the Declaration of Independence as the South’s new faith. Driven by this alternate conception of politics based on inequality, many of the slave states rejected the results of Lincoln’s election in 1860, and the nation was plunged into war.

Today, we face a parallel problem.

The true believers (who, not coincidentally, were also the true beneficiaries) of the blue church administrative state have also become alienated from the idea of republican government and shared citizenship. This can be seen most clearly in their unwillingness to accept the results of the 2016 presidential election, and the demonization of Trump voters. Like most privileged elites, their faith is immune to facts or persuasion. It is simply too hard to give up the notion of natural or divine sanction for the socio-economic superiority they have enjoyed.

With each passing day, this crumbling oligarchy seems to become more fanatical, more fixated on its own righteousness, and more impatient with the supposed iniquity of its political opponents. But the rejection of dialogue and compromise undermines the very possibility of a common citizenship. Without a shared dedication to republican principles, self-government cannot continue.

The peaceful transfer of power that accompanies a free election is only possible on the basis of civic friendship and trust; each side must believe that, win or lose, the rights of the minority will be protected by those who take power. On both sides today, that trust seems to be slipping.

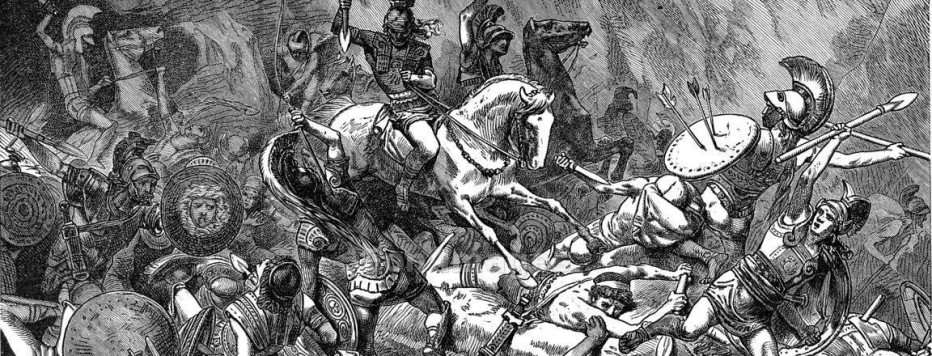

While most Americans acknowledge the fact that America is deeply divided, many of our leaders remain in denial about the potential result of this growing, fundamental distrust. We are confronting again the dire situation New Birth describes prior to the Civil War: “both parties [see] the contest as a zero-sum enterprise in which the advantages of one side [are] losses to the other. From this viewpoint, ballots can never really substitute for bullets.”

Not for the first time in our nation’s history, if this state of affairs continues force may be embraced as the only alternative when reason fails. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

We must fervently hope that things will change before they become violent. But if the clueless attitudes of our sclerotic elite remain unaltered, it is not hard to see what’s on the horizon.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

In 2010, Claremont Institute Senior Fellow Angelo Codevilla reintroduced the notion of "the ruling class" back into American popular discourse. In 2017, he described contemporary American politics as a "cold civil war." Now he applies the "logic of revolution" to our current political scene.

Claremont Institute Senior Fellow John Marini is one of the few experts on American Government who understood the rise of Trump from the beginning of the 2016 election cycle. Now he looks to the fundamental question that Trump's presidency raises: is the legitimacy of our political system based on the authority of the American people and the American nation-state, or the authority of experts and their technical knowledge in the service of "progress"?