More citizens are rejecting the woke gods in favor of the God of old America.

The Paradoxical Perversities of Postcolonial Ideology

This ideology is incompatible with the flourishing of the West.

Postcolonialism, as we have already made abundantly clear, has nothing to do with a disinterested inquiry into the truth, or even a fair-minded evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the West’s dynamic, but imperfect, civilization. Rather it is an ideological current that delights in denying any moral legitimacy to the most self-critical civilization in human history, an approach where history is weaponized and distorted beyond all recognition. As the French political philosopher Pierre Manent has suggested, if apolitical humanitarianism is a perversion of charity, wokeness, which animates postcolonialism, perverts the Christian call to repentance. In a world without original sin, some are ontologically guilty and beyond redemption, and others, those deigned victims, are shorn of moral agency and remain forever “innocent” as if in some idyllic prelapsarian state. At the center of this perverse parody of old Christian truths and virtues is the pathological self-loathing which we began to analyze in the first two contributions to this series.

A most welcome intellectual antidote to this ideologization of historical inquiry, guilt, and judgment can be found in a recent and widely discussed book by the English theologian and ethicist Nigel Biggar entitled Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, published by William Collins in 2023. Bloomsbury, his original publisher, refused to publish the book after an academic/activist mob descended on it. Without reviewing the book per se, I will highlight some of its principal insights while providing illustrations and insights of my own.

Biggar, a Christian realist of the Niebuhrian type, never confuses moral judgment with moralistic fanaticism or facile and predictable condemnations. He follows the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, the author of Things Fall Apart, who shortly before his death in 2013 told an Iranian journalist that “the legacy of colonialism is not a simple one but one of great complexity, with contradictions—good things as well as bad.” Achebe strongly opposed colonialism per se, in large part because it made of the native population “some kind of ward or minor requiring protection.” But he admired the good work of Christian missionaries who provided him and his father with fine educations, and he noted with appreciation the relative absence of corruption in the British colonial administration. The contrast with post-independence Nigeria could not be any more striking, he observed.

A reader of Biggar’s book will learn that Canada’s loathed residential schools for the native population were hardly hellholes and did much good in training and educating young Indians. They sometimes went too far in discouraging the study of native languages and native religious traditions, though as Christian clergy, they could hardly be faulted for taking the “Great Commission” seriously. Charges of “cultural genocide” against them are hyperbolic.

Biggar ably demonstrates how forced the contemporary identification of racism, slavery, and colonialism really are. To be sure, he is sensitive, as any decent person must be, to the terrible cruelties of the Atlantic slave trade (even if—one of the many important points of the book—the West had no monopoly on the evils associated with slavery and the slave trade). In his book we meet, in his own words, “brutal slavery, the epidemic spread of devastating disease, economic and social disruption; the unjust displacement of natives by settlers; elements of racial alienation and racial contempt” and more. But, at the same time, the British were a comparatively humane colonial power, and “[I]n the history of the British Empire, there was nothing morally comparable to Nazi concentration or death camps, or to the Soviet Gulag.” Moreover, there were powerful countervailing tendencies that need to be taken into account, including the massive campaign that Britain and her navy waged against the international slave trade for most of the nineteenth century in the years after 1833. In that admirable and sustained effort to united “justice and force,” in Pascal’s memorable and suggestive phrase, the British did themselves proud.

Lord Palmerston took particular satisfaction in the role that he and the British government played in forcing Brazil to end the slave trade in a country where slavery was at once most brutal and deadly. Christian morality (think of William Wilberforce’s long and ultimately successful struggle against slavery and the slave trade) and liberal principles increasingly influenced British policy, and both for the good. Biggar even rescues the reputation of the much-derided Cecil Rhodes—colonialist, mining magnate, and adventurer par excellence. Rhodes never denied the common humanity shared by blacks and whites, and he supported suffrage for blacks and mixed-race persons in South Africa who met certain educational and property requirements. Many of the hideously racist sentiments (and quotations) attributed to Rhodes by hostile biographers and activists have been made up whole cloth and then endlessly recycled by even more hostile activists. Truth is the first victim of ideologically inspired historiography.

Ideological Musings

Let me add some examples of my own to show that the ritualistic identification of empire with slavery and racism is far more ideological sloganeering than measured political and historical analysis. The counter examples are abundant and instructive. Edmund Burke, the great Anglo-Irish parliamentarian and political philosopher, despised slavery and wrote “A Sketch of the Negro Code” in 1780 in order to lay out a workable plan for gradual emancipation. He loathed Warren Hastings’s heavy-handed direction of the East India Company, accusing the governor general of corruption and cruel disdain for long-established Indian customs. Hastings, Burke suggested, ruled India like a rapacious, conquering army. Burke spent 12 years fiercely pursuing an ultimately failed impeachment of Hastings.

Burke also took pointed aim at the anti-Catholic penal laws in Ireland and argued that the majority Catholic population needed to be brought into the political community, their rights respected, and their interests represented (at least partially), in the Irish parliament. It is true that Burke never condemned empire per se. But he worked for an empire whose spirit was humane and magnanimous, rather than heavy-handed and dominated by self-aggrandizement and a petty concern for lucre. As such, he was a partisan of civilized and civilizing empire, however contradictory that might seem to our contemporary postcolonialists. For them, condemnation and self-loathing are the alpha and omega of postcolonial discourse and ideology. They desperately need to expand their moral imaginations.

Alexis de Tocqueville favored the French conquest of Algeria, even as he vigorously fought slavery at home and abroad. In 1855, he wrote an open letter to Americans, published in the abolitionist journalist Liberty Bell, expressing his unease at “seeing Slavery retard” America’s “progress, tarnish her glory, furnish arms to her detractors, [and] compromise the future career of the Union.” He spoke about being deeply “moved at the spectacle of man’s degradation by man.” A supporter of civilized empire, Tocqueville detested both slavery and racism and opposed any effort to forcibly convert Algerians to Christianity from Islam (even though he thought the “fatalism” of Islam deterred social progress and was in the end incompatible with robust intellectual and political freedoms). The terrible simplifications of the postcolonial ideologues cannot begin to do justice to the complex judgments and moral bearing of a thinker and statesman such as Tocqueville.

For his part, the great Winston Churchill fiercely opposed the precipitous granting of independence to the peoples of the Indian subcontinent. But his motives were hardly racist. He feared that Hindus and Muslims might butcher each other if the British were no longer there to moderate and arbitrate their respective communal demands. (In the event, Partition was attended by mass violence and wholesale human slaughter in 1947 and 1948.) Churchill did not want Britain to be responsible for unleashing “primordial chaos” in a country for which she had long had responsibility. In a 1931 speech, he took aim at India’s Brahmin elite whom, he said, prattled on about “the rights of man” even as they ignored and belittled India’s long-suffering “untouchables.” In that same speech, he even suggested that if Christ were to come back to earth, he might first go to minister to the “untouchables of India” in order “to give them the tidings that not only are all men equal in the sight of God, but that for the weak and the poor and downtrodden a double blessing is reserved.” This is hardly the voice of an advocate of genocide, cultural or otherwise.

Today, the fevered Left (and those too ignorant or cowardly to stand up to them) dismiss Churchill as an imperialist and worse. They quote him selectively and confuse a defense of empire with a bent for cruelty, exploitation, and even genocide. But that is not how Churchill saw things. After panicked British troops opened fire on unarmed Indians in Amristar in 1919, Churchill condemned the massacre unequivocally and forcefully. He spoke, echoing Macaulay, of “the most frightful of all spectacles, the strength of ‘civilization without its mercy.’” Here magnanimity meets humility in a truly admirable way.

A Balanced Judgment from the East

Unlike the array of postcolonialists who mercilessly condemn the West and deny its moral legitimacy (and thus its right to exist), Biggar points out that in July 2005, then Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, in a speech at the University of Oxford weighing the credits and debits of British colonial rule in his native country, generously acknowledged “the beneficial consequences” of British rule in India, including rule of law, constitutional government, a professional civil service, and modern universities and research centers. He tellingly added: “Our constitution remains a testimony to the enduring interplay between what is essentially Indian and what is very British in our intellectual heritage.”

The postcolonialists are incapable of sharing Singh’s equanimity and balanced judgment. As Biggar puts it, their “exaggeration of colonialism’s sins is often not at all reluctant, but willful, even gleeful.” Theirs is a nihilistic inversion of Christianity, a perverse “anti-Christian Christianity” as René Girard has called it, where the West can do nothing right and the “Other” can do no wrong. In their self-understanding, the West remains at the center of world history but as the Evil Empire, the pariah to be cancelled and excluded until the end of the world.

Self-Hatred as a Weapon

“There is a self-obsessive quality to this attitude,” Biggar notes. For his part, Biggar worries that the continued inculcation of nihilism as perverse self-righteousness will continue to undermine the self-confidence of those trusted to preserve a liberal international order friendly to humane Western values. But perhaps that particular train has already left the station. Instead, self-abnegation already plays a crucial role in an emerging woke imperium where democracies fight an ill-defined racism, promote LGBTQ+ ideology, and mock the Christian principles that led free peoples to take on slavery and the slave trade as incompatible with modern “freedom.” Postcolonialism, alas, is already a defining feature of the public philosophy, the ruling ideology, of progressives everywhere in the Western world. That, alas, does not bode well for historical truth or the future of Western liberty.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Caricatures and lies abound in the attempt to subvert the West.

Half-truths are no antidote for lies.

Condemning the West is as morally dangerous as it is intellectually bankrupt.

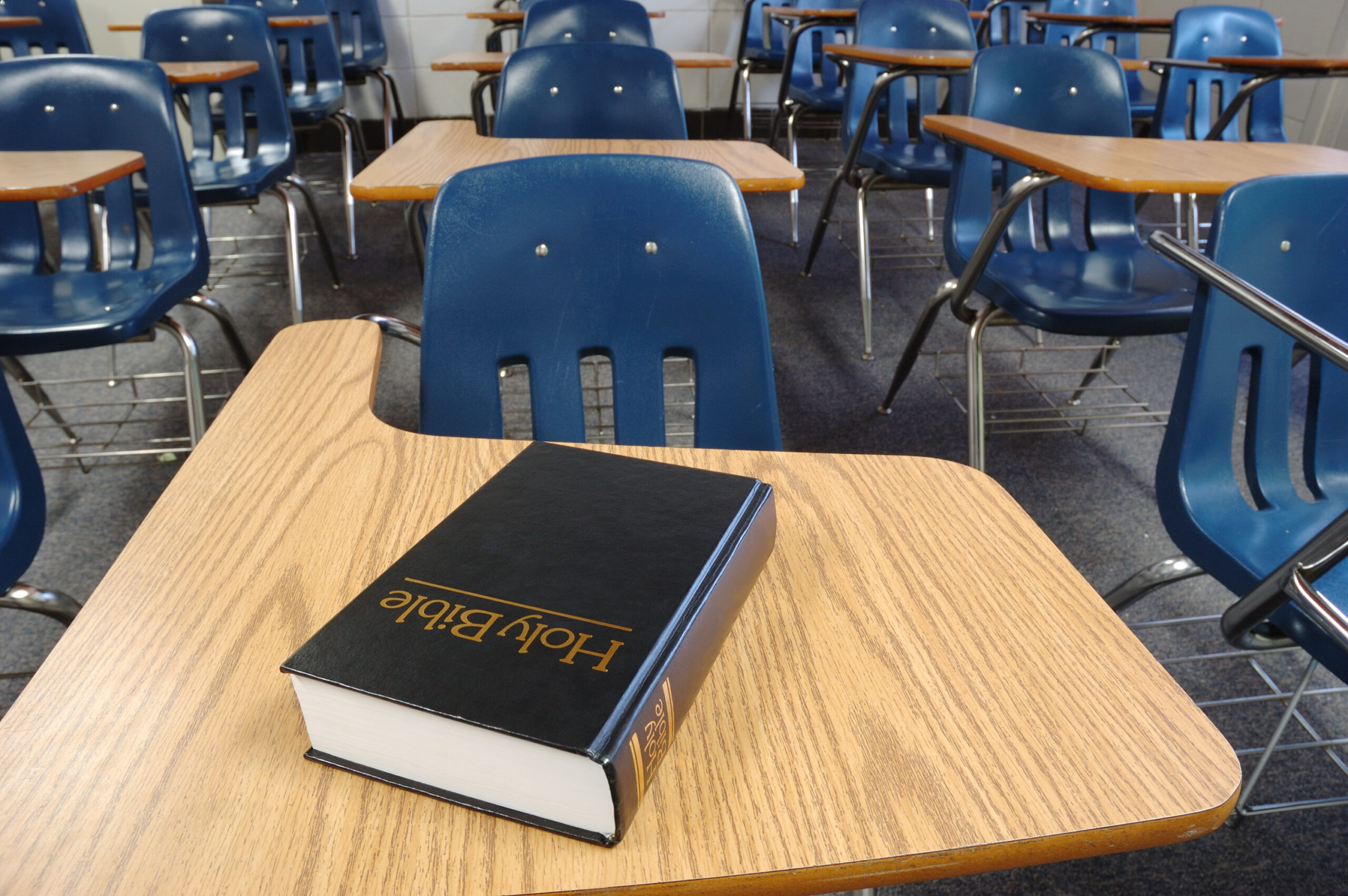

Oklahoma could make a giant leap for K-12 education.

The replacement of Easter by this new feast day in the progressive liturgical calendar is a provocation.