Christians need to find the will to act.

What Is Christian Nationalism?

It’s far more than the latest ad hoc term for everything the regime despises.

The subject of Christian nationalism generates little light but much heat.

Since at least the publication of Michelle Goldberg’s Kingdom Coming: The Rise of Christian Nationalism in 2006, the ruling class has used the term as a club to bludgeon evangelicals—especially in the wake of their prodigious support for Donald Trump in the 2016 and 2020 elections.

Christian nationalists, the mainstream press tells us, are racist, QAnon-addled election deniers. They want to Make America Puritan Again (in the modern, badly misunderstood meaning of that word). And they believe that the Constitution should be set aside for a Christian divine-right king who will oversee forced religious conversions and impose draconian moral codes upon an unwilling populous.

The Washington Post’s Jennifer Rubin has called Christian nationalism “an authoritarian, racist, dogmatic message donning the cloak of Christianity,” asserting that the GOP is “dedicated to imposing White Christian nationalism” on the country. A coterie of chin-stroking panels hosted by D.C. think tanks, “democracy” experts and sociologists, and (former) Republican members of Congress have condemned it in the strongest possible terms.

Evangelicals who aspire to be accepted by the ruling elite make a point of agreeing in full with the received view. Christianity Today editor-in-chief Russell Moore described Christian nationalism as “liberation theology for white people.” David French, who never misses the chance to steamroll his fellow evangelicals in the New York Times, called it “a blueprint for corruption, brutality, and oppression.”

The riot at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021 has been packaged as the perfect showcase of Christian nationalism’s devastating consequences for America. All Americans are required to say that Christian Trump supporters tried to overturn “our sacred democracy” and made an idol of Trumpism at the expense of their eternal souls. (Ethics Professor Daniel Strand has conclusively shown that critics flew to this ready-made narrative before any evidence was presented.)

Mainstream conservatives, for their part, generally argue that liberals indiscriminately and unfairly employ the label against all conservatives, who are for the most part not Christian nationalists but patriotic Americans. However, as that contrast implies, this defense of conservatism takes for granted that the ruling class portrait is an accurate one: Christian nationalism stamps out religious freedom and coerces people into false belief. As Hillsdale College’s D.G. Hart wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that was published close to Independence Day, Christian nationalists long to return the nation to “pre-1776 patterns of government, such as John Calvin’s Geneva or John Winthrop’s Boston,” where “the civil magistrate supported churches and cajoled citizens to practice faith.” Conservatives like Hart worry that Christian nationalists will drag us back, Handmaid’s Tale-style, to a benighted age that we worked very hard to leave behind.

Both the Left and a good portion of the Right then agree that Christian nationalism ought to be rejected by all good and decent Americans. But does it truly represent the ultimate threat to the American republic? Is it the dying gasp of a hidebound folk religion that signifies the closing stage of a less-refined epoch? Is this how Christian nationalists understand themselves?

While the Claremont Institute takes no institutional position on the question, we must take Christian nationalism seriously. The debate over it represents a new stage in the ongoing realignment of our politics and culture, touching directly on how Americans should regard and relate to ultimate questions of the human soul and the highest good. The rise of Christian nationalism, along with post-liberalism, Catholic integralism, and other overlapping yet distinct attempts to answer the deepest theological-political questions facing our nation, speaks to mounting levels of dissatisfaction with our current failing paradigm. Wishing away this obvious reality and holding fast to the dead consensus will only fuel greater levels of discontent with the status quo and heighten the chances of our nation’s disintegration.

Just as President Trump’s first presidential run offered the opportunity for a searching reconsideration of the post-Cold War political consensus, the rise of Christian nationalism likewise offers us the same opportunity in the realm of church and state.

Who Are You?

Critics like to suggest that the leaders of the Christian nationalist movement are universally members of an outlandish coalition: explicit pro-MAGA churches; pastors who hold star-spangled, “patriotic” services; Charismatic snake handlers; prosperity Gospel grifters; and Donald Trump’s less-than-orthodox circle of evangelists. Though these groups publicly promote a certain strain of Christianity, they are not supplying the leading theological and political arguments for Christian nationalism (even though they may reside somewhere in the fold).

Rather, the group leading the Christian nationalist movement is a small pan-Protestant coalition of Christians from multiple denominations (e.g., Presbyterians, Baptists, and Anglicans) who want to restore the political theology of the Magisterial Reformers. Works in this tradition include Martin Bucer’s De Regno Christi, Theodore Beza’s The Right of Magistrates, and Samuel Rutherford’s Lex Rex. And pivotal Protestant confessions that inculcate such views are the original Westminster Confession of Faith, the Belgic Confession, the Irish Articles, and the Thirty-Nine Articles.

The arguments that buttress this project are limited to a few books—with just one systematic treatment among them so far, Stephen Wolfe’s The Case for Christian Nationalism—a number of lengthy essays (some of whose authors do not even call themselves Christian nationalists), and assorted private group chats. There are no foundations or nonprofits solely dedicated to advancing Christian nationalism. Very few institutions would dare publish anything sympathetic with its aims.

Christian nationalists see themselves as leading a counterrevolution against the post-World War II order. In a bracing series of aphorisms in his book’s epilogue, Wolfe describes the Left as the managers of New America who have long since discarded the founders’ Constitution. They have captured virtually every major public institution and are working zealously to stamp out any vestige of Old America, with its heroes, traditions, and ways of life. The inheritance our forefathers left us has been rejected in favor of a toxic cocktail of oligarchy, feminism, transgenderism, and wokeism. Even the U.S. military, once thought unassailable, is in service to the Global American Empire—an online moniker given to America’s imperial project of exporting “universal principles” (in truth particularist claims that benefit certain “dispossessed classes”) to foreign lands. All told, Wolfe asserts, “Americans live under an implicit occupation; the American ruling class is the occupying force.”

Christian nationalists see the suppression of traditional Christian teachings and practices in public as a defining element of this occupation. This includes: a series of disastrous Supreme Court rulings on the First Amendment’s religion clauses; hoary clichés such as the “neutral” public square and the supposedly impregnable “wall of separation” between church and state; and “religious liberty” that allows Christian business owners to be sued into oblivion. As Kurt Hofer has noted at The American Mind, Christians “have accepted the terms of battle dictated to us by liberalism—we have, in effect, already conceded defeat.”

The pushback to our current regime has either been completely ineffective or nonexistent. The modern conservative movement’s often facile and uncritical embrace of open markets, open trade, and (in many cases) open borders has helped strip mine America of its once plentiful resources and contributed to our present disorders. Meanwhile, Wolfe argues that a group of Protestant regime theologians have been busy reconciling evangelicals to their dhimmitude status, ensuring that they will never pose a threat to unraveling the 21st-century moral consensus.

Longhouse Nation

According to Christian nationalists, America’s men inhabit the Longhouse. In First Things, the anonymous writer L0m3z described that now ubiquitous online term as the “overcorrection of the last two generations toward social norms centering feminine needs and feminine methods for controlling, directing, and modeling behavior.” Christian nationalists argue that modern feminism’s fatwa against “toxic” masculinity pathologizes healthy masculine virtues and renders men subservient and docile. Innumerable pits of quicksand are ready to engulf any man who makes a wayward step: kangaroo tribunals led by college administrators ready to prosecute the merest suspicion of sexual misconduct, heavily biased family courts, and phalanxes of white knights and doxxers on social media apps who seek to destroy the lives of those who run afoul of regime-approved orthodoxies.

Amidst this carnage, Zoomers and young Millennials are searching for a path by which they can achieve greatness, excellence, self-mastery, and vitality. This is why men in these circles have exhorted being in good shape, lifting weights, and eating right—not due to a base materialism but because preserving the physical body is an implication of the Sixth Commandment. And they champion other aims, including getting (and staying) married and having kids, building productive households, buying land and establishing anti-fragile homesteads, and being engaged in every facet of their local communities.

Above all, Christian nationalists reject the status to which Christians have been assigned: naïve patsies who believe that Christ’s teachings mandate the destruction of one’s nation and people. They want nothing to do with year-zero theology, the notion that Christianity best flourishes when Christians have no political power and face routine persecution and martyrdom.

Instead, they are looking to recover the collective will of Christians and confidently assert their interests in public. They would heartily agree with Kevin Slack’s cri de cœur made in this publication that Christianity “must once again become a fighting faith, the inheritance of the battles of Edington, Tours, and Lepanto.”

Defender of the Faith

How, exactly, can a nation be Christian? Crucially, according to Wolfe, the term does not imply that every citizen needs to be a believer. Instead, Christian nations exist when “everyday life is invested and adorned with Christianity (e.g., Christian manners and expectations) and when life orients around distinctly Christian practices such as the worship of God (e.g., sabbath observance).”

And who makes up each nation? Wolfe argues that a nation’s material cause is a people who share a common ethnicity, that is, the traditions, manners, customs, and decorum around which groups naturally congregate (see John Jay’s argument in Federalist 2). These mutual ties are the foundation for the requisite civic friendship that is integral to a nation’s health and longevity. Though it will make no difference to his most impetuous critics, Wolfe explicitly rejects race-based arguments: “being ‘white’ is unnecessary both to recognize themselves in what I describe and to cooperate with someone like me in a common national project.”

These arguments point to the teachings of the Magisterial Reformers (as opposed to the doctrines held by Anabaptists and other separatists, which are far more representative of modern Protestantism). After cutting ties with papal authority, most 16th-century Protestants aligned themselves with civil magistrates. Through the means of civil law, the magistrate restrained and punished evil and rewarded good, made everyone aware of the moral law (from which the civil law derives its legitimacy), and, more controversially for us moderns, prepared the people to accept the truth of the Christian religion. Protestant political theorist Johannes Althusius once stated, “As Thomas Aquinas says, ‘to govern is to lead what is governed to its appropriate end.’” The magistrate therefore helped create a robust Christian culture that would prepare man for salvation; culture alone could never produce saving faith.

Because the Reformers saw that the law even touched on spiritual things (though only their outward manifestations, not their inward effects), legal historian Timon Cline argues that the magistrate was seen as “the defender of the faith (fidei defensor) and a protector of the church.” Article 23 of the Westminster Confession of Faith (1647) charges the magistrate to preserve “unity and peace” in the church, suppress “all corruptions and abuses in worship,” and even call synods together to decide questions of doctrine.

But with this said, the magistrate only possessed the civil sword: ecclesiastical officers held the keys to the kingdom of heaven and dispensed both Word and sacrament to their congregants. The Reformers aimed to desacralize the civil order to prevent the fusion of civil and ecclesiastical power into a single office, a view derived from their theory of the two kingdoms, the cornerstone of Reformed political theology. In this understanding, Christ rules over both the temporal and spiritual kingdoms, but in different ways, as each have distinct yet complementary ends. The temporal kingdom (chiefly guided by the natural law) includes all visible institutions, even the outward arrangements of the church in principle. The spiritual kingdom (guided by special revelation) is wholly interior, having “its seat within the soul” as John Calvin described it. This is why the civil magistrate cannot coerce the conscience into false belief—it is a power he was never granted.

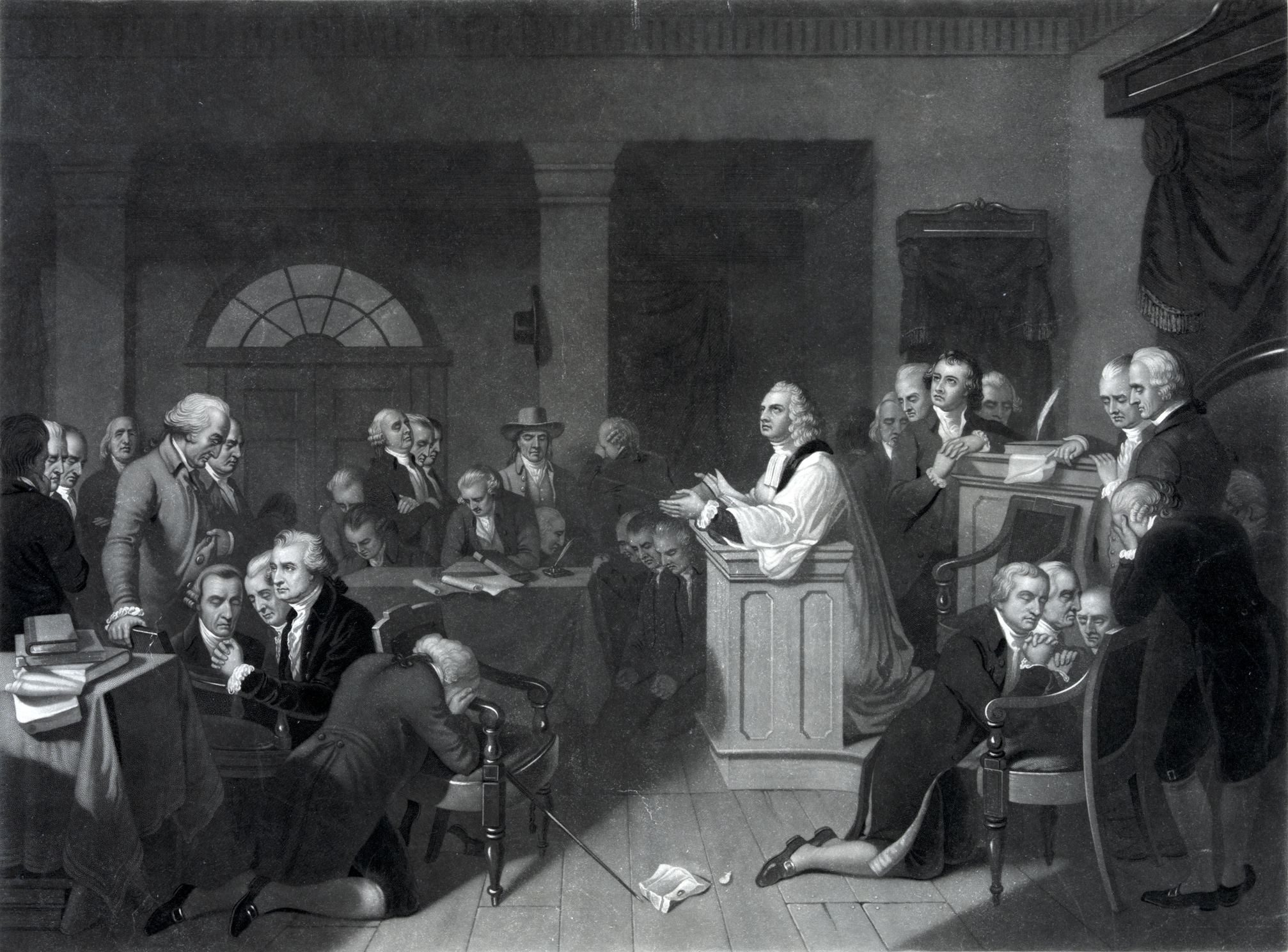

The History of American Christian Nationalism

What does this recounting of Reformed political theology have to do with America? After all, didn’t we separate church and state, promote an extremely capacious understanding of religious liberty, and sanctify pluralism? Christian nationalists contend that this is a gross distortion of the historical record. In fact, they argue that from our early colonial life until the mid-20th century, some key characteristics of America’s political and cultural traditions were already structured according to the logic of Christian nationalism. It is easy to forget that the Supreme Court ruled that the religious test clause in Maryland’s Constitution was unconstitutional—in 1961.

Politics professor Glenn Moots maintains that prior to the “de facto Protestant establishment undermined by incorporation of the First Amendment,” Christian nationalism is a fair description of the America “that Catholics like Tocqueville praised in the 1830s and Jacques Maritain acclaimed in the 1940s.” American history furnishes ample evidence that a non-denominational, Protestant form of Christianity at the very least undergirded the American view of law, morality, politics, culture, and public and private virtue. Though an avid opponent of Christian nationalism, historian John Fea has remarked, “Today’s Christian nationalists have a good portion of American history on their side.”

Colonial charters such as the Mayflower Compact (1620), the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (1639), and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) recognized that advancing Christianity, including inculcating it among the various native tribes, was a crucial aim. Historian Mark David Hall notes that “at least nine of the 13 colonies had established churches and all required officeholders to be Christians—or, in some cases, Protestants,” which was still the case when the first shots of the American Revolution rang out in 1775. Even the charter of Quaker Pennsylvania, the supposed bellwether of our modern notions of church-state relations, expected officeholders to “possess faith in Jesus Christ.”

As the colonies were organized into states, their religious character did not dissipate. While the First Amendment denied the federal government the power to establish a national church, it left state and local governments wide latitude to promote Christian morality and practices, a consensus that Gerard V. Bradley contended in the Summer 2022 Claremont Review of Books was in place until a series of woefully misconceived Supreme Court rulings beginning in the 1940s. The states were viewed as the locus of moral formation for citizens, in which Christianity played a pivotal role. At least six states—Georgia, South Carolina, Maryland, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire—had Protestant establishments even after 1776.

State constitutions of this period are replete with references to God, using such appellations as “Almighty,” “Creator,” “Governor of the Universe,” and “one God.” Nine of the 13 original states mandated religious tests for public office and limited office holding to Protestants. Furthermore, states generally privileged Protestantism, including using public funds to support religious schools and ministers, establishing Bible reading and prayer in schools, and prohibiting blasphemy and shuttering businesses on Sundays. There was thought to be no contradiction between preventing compelled religious belief and a de factoestablishment centered around maintaining the Christian faith.

“Religious liberty required only that individuals not be coerced to practice religion or penalized for not practicing it,” wrote Vincent Phillip Muñoz in the Fall 2017 CRB. Religious liberty was generally extended to those of other faiths on the condition that they respected the Christian faith. It was not an unlimited right that would have given Satanists the “freedom” to shred the Bible in public. Rather, its moral limits were hemmed in by the dictates of right reason and the good of the polity.

Though all formal state establishments were gone by 1832, Hall finds that most states still supported a “generic, non-denominational Protestantism” that “retained religious tests for public office, had laws aimed at restricting vice, [and] required prayer in schools.” Disestablishment was not due to a sudden acceptance of what passes today for classical liberalism. Instead, as Thomas G. West recently pointed out, inter-denominational resentments among Protestants fueled these efforts. Later disputes, this time between Protestants and Roman Catholics, would lead to the secularization of public schools in the post-Civil War period.

A Christian American Culture

Christianity’s impact on our country’s culture, refracted through the prism of American political life, cannot be overstated. “Throughout America’s history, preachers, statesmen, and ordinary citizens have constantly appealed to the language and the images of the Christian scriptures to make sense of their experiences and to call one another to a higher ideal,” writes scholar Brad Littlejohn. Christianity has saturated presidential speeches, Thanksgiving proclamations, calls for national days of prayer, countless Supreme Court opinions, congressional debates, and treaties. (The Treaty of Paris of 1783 opens by invoking “the Name of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity.”)

Christian themes are emblazoned upon our money, displayed in the Great Seal of the United States, and featured on numerous public buildings and memorials around the nation’s capital. West argues that even the theology expressed in the Declaration of Independence, with its references to God as “our lawgiver, creator, judge, and providential protector,” speaks to specific descriptions of the God of the Bible (Mark David Hall observes that these terms are virtually identical with the adjectives ascribed to God in the Westminster Confession of Faith).

Taking oaths of office by placing one’s hand on a Bible, opening legislative sessions with prayer, and the establishment of a vast network of Christian charities—all of this plus a mountain range of additional evidence led Justice David Brewer, writing for a unanimous Supreme Court, to conclude in Holy Trinity v. United States that the United States “is a Christian nation.” Like Brewer, Americans spanning the gamut from John Jay to Joseph Story to Woodrow Wilson to Harry Truman explicitly called America a Christian nation. The great Chief Justice John Marshall asserted that in America, “Christianity and religion are identified. It would be strange, indeed, if with such a people, our institutions did not presuppose Christianity.”

Clearly rejecting libertarian-liberalism, generation after generation of Americans promoted Christianity politically because they viewed it as a key buttress in supporting republican government. In his Farewell Address, George Washington counseled, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” Because “men are ambitious, vindictive and rapacious,” as Alexander Hamilton described fallen human nature in Federalist 6, it was necessary for the divine law to support the founders’ natural rights regime. Special and natural revelation would work in tandem to limit the worst effects of man’s crooked nature and inculcate the virtues of self-government for his own private good and that of the nation.

All told, the historical case is undoubtedly a strength of the Christian nationalist argument.

How Should We Then Live?

Moving into the realm of action, what do the prospects look like for Christian nationalism? For starters, the country described above clearly is no longer present. The people’s ability to govern themselves and their religious character are fading fast (even rural areas aren’t necessarily a bulwark of citizen virtue). And however sophomoric their tactics, the regime is still out for revenge, targeting those who hold to what until just a few years ago was viewed as standard Christian morality.

On the theological front, things look fairly bleak. Pastor Michael Foster recently noted that the Reformed denominations from which Christian nationalism draws the bulk of its intellectual firepower tend to be inaccessible even for a vast majority of Protestants. Even more stark, in a country of over 330,000,000, the Presbyterian Church in America, perhaps the largest explicitly Reformed denomination, has just a little over 390,000 members. Plus, if the latest Pew findings are to be believed, the number of Americans who consider themselves Christians will likely shrink from 64 to just 35 percent by 2070 if present trends continue.

Re-establishing a Christian nation in any meaningful sense seems a gargantuan task. Just consider how long it took for the successive waves of liberalism, from the early Progressives through mid-century, FDR-style bureaucratic liberalism then to the New Left and its progeny, to bring us to where we are today. Furthermore, a true counteroffensive would mean supplanting our second Constitution, established by the civil rights regime, with a third Constitution that protects the freedom of association, a core right that Thomas G. West notes is necessary for a robust expression of the freedom to worship. Absent a nationwide crack-up, it could take a century or more for the Christian nationalist project to have any measurable effect at scale.

In order for their project to have success, Christian nationalists would need to obtain and use political power, which is anathema to large swaths of evangelicals today, who tend toward some form of political anabaptism. Christian nationalists would need to exercise power in ways that not only counter our current regime but give due consideration to how the regime would respond in kind to such organizing.

Part of any serious political project involves building a new elite, which seems to be in some tension with the goal of living off the grid that many in this fold practice. An elite of some kind has and will always rule. Will Christian nationalists build theirs through a strategic use of existing institutions, or go completely outside of them, waiting to take charge when the situation presents itself?

As for the institutions themselves, it would require a multi-pronged, systematic approach to take them over or (far more likely) build new ones. This would also mean running for political office (not necessarily to win in the short-term but to build a network of allies, as Charles Haywood has counseled) and changing laws on the local, state, and federal levels of government. Likely allies and sources of funding include sympathetic supporters fed up with corporate life and outsiders with substantial, yet untapped, talent.

Additionally, there even remains a roiling debate over the term “Christian nationalism” and the effectiveness of that label in the American context. Christian nationalists, who need to be mindful of the importance of deploying the right rhetoric, should also be looking to make an appeal to the tens of millions of “Grill Americans” in the suburbs, whom they need to have in their ranks in some number to have success. The current use of very-online terms and tactics will need to make way for multiple rhetorical strategies that appeal to different cultural strata.

That points to perhaps the most crucial part of this project: prudence. Christian nationalists are taking up their project in a country that looks far different than it did in 1787, when the options were (overwhelmingly) which flavor of Protestantism one chose to join. It will take serious thought to translate the principles of Reformed political theology into a very different context. What may be true in principle could easily be counterproductive were it put into practice today.

Now some advice for the Christian opponents of Christian nationalism: making heated denunciations without carefully examining the arguments at issue will only prop up the existing order. Flinging casual accusations of racism, among other -isms, and unironically citing smears from leftist institutions is simply doing the Left’s work for them, clearing the field of any opposition. If Christian nationalism needs healthy and good-faith critique, fellow Christians are the ones to offer it. Christians cannot afford to slander one another using the Left’s simplistic categories.

Nor can conservatives of any kind afford to disregard energetic movements that are serious about taking back power—they are too few to be ignored wantonly. Indeed, one major reason for optimism in the Christian nationalist fold is that they have evidently learned from the failures of the conservative movement and are working on developing a positive program, not merely a defensive strategy. And they have a convincing, historically-based case that highlights the deep imprint of America’s Protestant character that remains even today, however trampled upon and bruised. They are not importing a framework that is completely alien to the traditional American way of life. Mocking them will not make them go away, nor will the issues they raise evaporate if they fail politically. Whatever its future, Christian nationalism is a force to be taken seriously.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Christian nationalism is a long overdue attempt to revive American’s political and cultural heritage.

It takes more than online wishcasting to win elections.

Some labels are just about chasing normal people out of the polite mainstream.

A time for choosing.

Neither liberal theologians nor online anons offer a plausible way forward.