Christians need to find the will to act.

Christian Nationalism or Godless Nationalism

A time for choosing.

Advocating Christian nationalism may seem, at first blush, like a futile enterprise. We live in a country that is de-Christianizing rapidly. America is expected to lose its Christian majority by 2050 and be just 39 percent Christian by 2070. As even Mike Sabo acknowledges in his introductory piece on the subject, “Absent a nationwide crack-up, it could take a century or more for the Christian nationalist project to have any measurable effect at scale.”

Yet despite this, the debate over Christian nationalism has taken on mythic proportions in certain corners of the Right. Christian nationalism has a variety of definitions among those versed in the relevant arcana. As a layperson (literally and when compared with the initiates in these debates) I will adopt a broad and basic but serviceable definition: Christian nationalism is the view that America’s institutions should bear the influence of, and move people toward, Christianity. This definition could obviously include a large variety of policies and perspectives, but it has the virtue of encompassing the vast majority of the Christian nationalist project, while being broadly comprehensible to the average churchgoer.

Before examining the positive case for Christian nationalism, it is instructive to examine the arguments of some of its fiercest critics. Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a professor of history at Calvin University and author of Jesus and John Wayne, perhaps the most popular current critique of the white evangelical community, told an interviewer that “at the core of Christian nationalism in contemporary politics is really the idea of privileging certain views over others, in terms of determining our laws, in terms of even interpreting our Constitution, and in terms of implementing our democracy.”

Well yes, that’s actually the idea. As Christians we should privilege a Christian viewpoint, I think, rather than the godless viewpoint that has been forced on America, largely illegitimately, by the courts over the past several decades. Of course, this approach could be taken too far. Russell Moore, editor of the liberal quasi-evangelical magazine Christianity Today, cites the case of the Russian Orthodox patriarch who recently implied that military sacrifice in the war versus Ukraine would wash away all sins. Or witness the tight integration between church and a conservative state that can ultimately damage both, as we recently saw in Poland. But while a state which embraces Christianity too closely can cause a collapse in Christian faith from without, a fully-secularized state such as our modern one can also rot the moral foundations of a society from within.

That is to say, while Moore’s attack on Christian nationalism in Russia is fair, he goes too far when he claims that Christian nationalists use “Jesus’ authority to baptize their national identity in the name of blood and soil.”

This is not a description of Christian nationalism that those Christian nationalists I know would embrace. Of course Christianity is a universal religion—there are obviously certain core beliefs. But, as missionaries have learned over many generations, Christianity’s ability to embrace particularities is often as powerful as its universality. What leads people to the Gospel and keeps them in the community of believers can be almost infinitely varied depending on the cultural and national context. Simply put, “nationalizing” Christianity in the sense of localizing, particularizing, and institutionalizing it in a particular place and culture is necessary for the very real work of saving souls. A Christianity that excludes a national mission or that does not integrate with an existing cultural context is a Christianity that will likely fail to save souls for Christ.

Or, as noted Presbyterian theologian Carl Trueman wrote in a balanced and perceptive article: “To love one’s country, to be patriotic, is…not to sneer at every other nation or to look with scorn upon other peoples. It is simply the appropriate response of gratitude and love for the place where one belongs, that gives one an identity, that provides one with community and with purpose.”

Our Christian Nationalist History

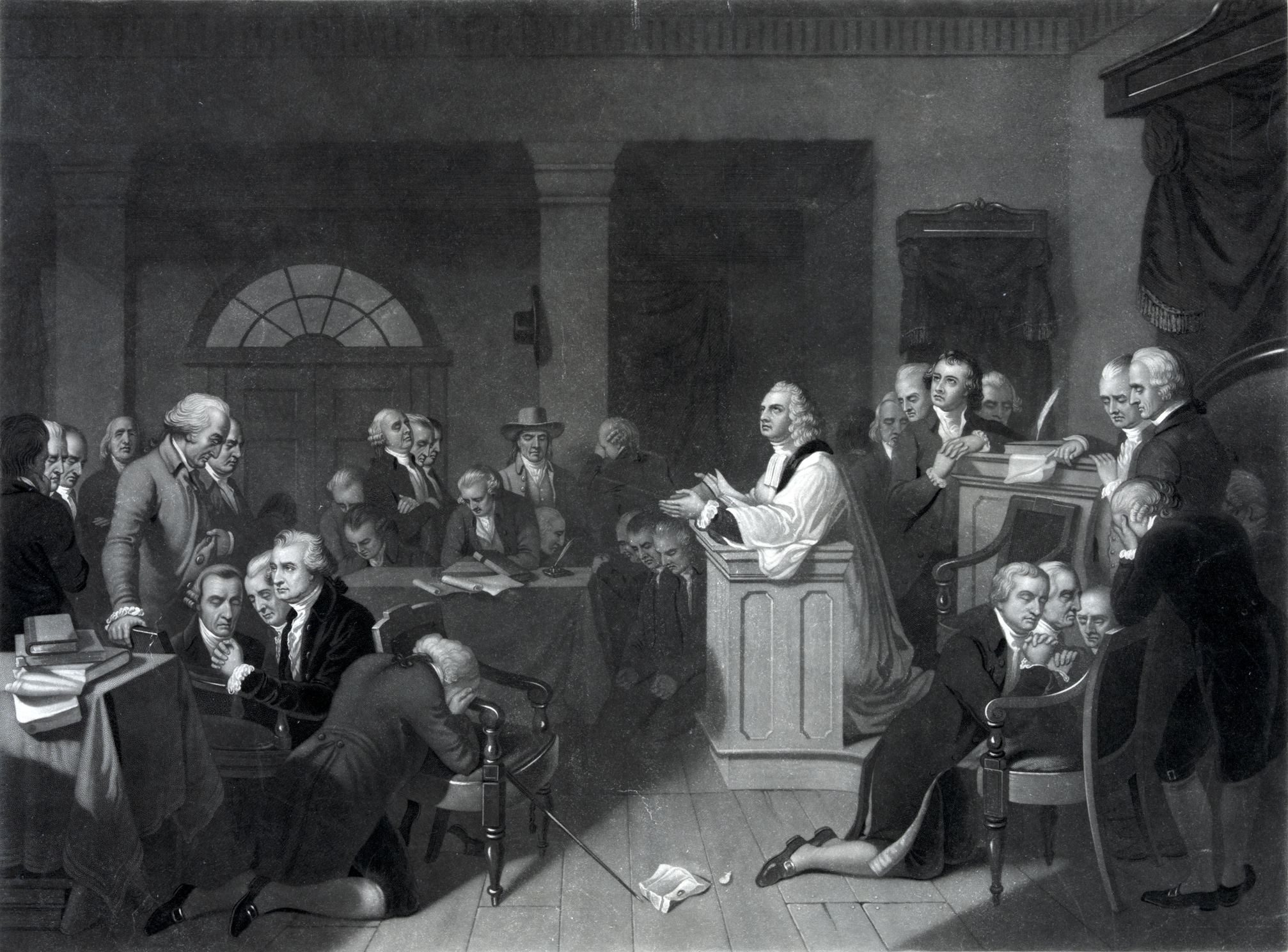

So why promote Christian nationalism? One reason is that it has been shown to work in an American context previously. A version of Christian nationalism grew America from an obscure collection of colonies hugging the Eastern seaboard of North America in the 17th and 18th centuries to the world’s greatest economic and political powerhouse by the early 20th century. No founder seriously disputed the goal of encouraging Christianity among the populace.

Even the two most famous early examples of the alleged “separation of church and state” were public diplomatic gestures, not forthright descriptions of reality in the founding generation. Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists, in which he famously alluded to a so-called “Wall of Separation” between church and state, came from the least religious founder to a denomination concerned about their unfavorable treatment in Connecticut. And the notion that America is “Not in any sense founded on the Christian religion,” is found in the Treaty of Tripoli (1797) made with a Muslim power, a public declaration that was possibly shrewd diplomacy but did not really reflect American reality.

By contrast, the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War, began by invoking “the Name of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity.” A unanimous Supreme Court in the 1890s signed on to an opinion stating that the United States was “a Christian nation,” a phrase repeated by presidents as late as Harry Truman.

When the Revolutionary War began, every single colony required Christian belief from officeholders (and in some cases Protestant belief—98 percent of the colonists were Protestants). Even after the revolution, nine of 13 original states had state churches, the last of which was not abolished until 1833.

States in early America generally promoted Protestantism and used public funds to pay ministers and support religious schools, while establishing school prayer. (Indeed, it was the fact that they were not the recipients of such public largesse that had the Danbury Baptist miffed.) But it may reassure our current multi-religious population to know that Christians were not the only people who benefitted from this Christian nationalist regime. As the late, renowned historian Paul Johnson noted in his study of the Haskalah, the “Jewish Enlightenment” of the 18th and 19th centuries, it was thanks to the extension of civil rights to all groups under Christian governance and social norms that Jewish secular achievement and societal integration was finally able to flourish.

An analysis by Donald Lutz of 18th-century publications in the colonies show the colonists cited the Bible far more than all Enlightenment authors combined. To the extent they did not talk about explicitly Christian governance, it was for the same reason that if fish could talk, they probably wouldn’t discuss the sea. Indeed, legendary Chief Justice John Marshall acknowledged, “It would be strange, indeed, if with such a people, our institutions did not presuppose Christianity, & did not often refer to it.” Even today, public institutions shut down on Christmas.

Nor was the Christian character of America merely an obscure artifact from the country’s earliest days. As late as the turn of the 1960s, a federal appeals court agreed that Maryland could restrict officeholding to religious believers until its ruling was overturned in Torcaso v. Watkins (1961). This decision drew on the 1947 case Everson v. Board of Education, which held that the Establishment Clause was incorporated against the states. Prior to the Everson decision, many states had given privileges to particular denominations. The so-called Lemon Test of 1971, in Lemon v. Kurtzman, declared that government actions must have a secular legislative purpose—a ruling that has only recently been scaled back somewhat. Today’s godless Constitution was not the Constitution that the Founders would have agreed to or even recognized. It was created between the 1940s and the 1970s by an increasingly radical Supreme Court which chipped away at America’s Christian heritage without basis in constitutional text or history. America in its mid-20th-century heyday was culturally Christian—my non-Christian parents grew up singing religious Christmas songs in school without anyone thinking that their civil rights were violated.

The Dangers of a Christ-Less Public Square

The new secular ethos demands we carve out limited exceptions for Christian belief in an aggressively anti-Christian state. This is not a model to aspire to.

As Kurt Hofer wrote at this website: “If one key insight has emerged from America’s religious Right—Protestant and Catholic alike—in the (post)Trump era, it is this: Christians operating within the liberal paradigm of private religion and spurious public “neutrality” have accepted the terms of battle dictated to us by liberalism—we have, in effect, already conceded defeat.” Mere tolerance is all that is on offer, and this tolerance will not last for long. While the Gospel, and not politics, must always be at the center of the church, the absence of politics from the church is often just cowardice disguised as high-mindedness. Many “conservative” Christians seem to be moving toward an extreme anabaptist politics, in which religious activity is merely performative—a virtue signal unwedded to any practical outcome.

Noted Christian nationalist thinker Stephen Wolfe has written critically about such apolitical thinking among Christians: “[their] political thinking is, in the end, purely apologetical…. The local church within its walls demonstrates ‘true politics’ and ‘true justice’ to the world, but forbids both the formulation of any realistic Christian political program and the use of civil power to shape civil society in accordance with that formulation.” Such a stance is obviously not seriously political. But more importantly, because it disclaims the consequences of church action in this world entirely, it is not seriously Christian either. Wolfe correctly refers to those wishing to act in this way as “state theologians” who work to marginalize actual dissent from our current anti-Christian regime. There are many practical benefits to becoming a servant of the regime in this way, but few are eternal.

While moral witness is important, an exclusive emphasis on “moral witness” rather than concrete political achievement is a permanent excuse for defeat. For centuries, Christian polities did not simply confine themselves to “moral witness,” but to practical victory. Had Christians relied solely on moral witness rather than force of arms at the gates of Vienna, Europe would likely not be Christian today. And by failing, in the name of “compassion,” to speak out about the flood of Muslim immigration into Christian lands, quietist Christians are quickly erasing the victories their forefathers struggled so mightily in Vienna to achieve. The wages of this inaction can be seen in the streets of Europe (and, to a lesser degree, America) today.

As Sabo writes “above all, Christian nationalists reject the status to which Christians have been assigned: naïve patsies who believe that Christ’s teachings mandate the destruction of one’s nation and people. They want nothing to do with year-zero theology, the notion that Christianity best flourishes when Christians have no political power and face routine persecution and martyrdom.” Martyrdom is sometimes necessary for Christians in the political arena, but it is not the sine qua non of a serious Christian politics. Instead, we should embrace Hillsdale Professor Kevin Slack’s call to action, made in this publication, to the effect that Christianity “must once again become a fighting faith, the inheritance of the battles of Edington, Tours, and Lepanto.”

The disavowal of truth claims and their implications unfortunately has a long history in establishment Christianity, one that grew in parallel with the decline of American Christian nationalism in the mid-20th century. In his 1978 book No Offense: Civil Religion and Protestant Taste, sociologist John Murray Cuddihy discussed how 20th century Protestantism neutered itself by renouncing its claims on truth in the name of comity, thus allowing establishment ecumenical theologians like Reinhold Niebhur to become the voices of “respectable” Christianity in exchange for backing off any serious contentions of universal Christian truth. Stripped of their claims to universalism, mid-century Americans were deprived of the ability to see human existence through a religion that took its theological claims seriously. In this world, accommodations in fundamental matters of belief were seen as “good taste.” In the 21st century, critics of Christian nationalism want us to have a society of such “good taste” that requires we abandon eternal truths as a guidepost for governance. The bad results of that “good taste” are visible in the social decay all around us.

There are implications to this surrender. As Hillsdale’s Thomas West notes, a serious Christian nationalism must engage in a potentially unpopular challenge to existing civil rights laws, which “frequently limit religion as practiced outside of the narrow realm of ‘religion as such’…. Civil rights laws protect the right of unwed mothers, gays, and transgenders to nondiscrimination—which means religious schools or businesses may be required to admit them or hire them, contrary to their Christian moral convictions.” In such a situation, where Christianity cedes the public square to state atheism, it can become functionally impossible “to follow and teach in daily life the moral beliefs of Christianity as understood by most believers.”

Understood rightly, therefore, the question in our current situation is not whether Christian nationalism is a worthy object of our aims, but whether in the current year it is really possible, if we do not embrace at least some of the claims of Christian nationalism, to practice Christianity at all.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

It’s far more than the latest ad hoc term for everything the regime despises.

Christian nationalism is a long overdue attempt to revive American’s political and cultural heritage.

It takes more than online wishcasting to win elections.

Some labels are just about chasing normal people out of the polite mainstream.

Neither liberal theologians nor online anons offer a plausible way forward.