Christians need to find the will to act.

American History Is Protestant

Christian nationalism is a long overdue attempt to revive American’s political and cultural heritage.

Finally, American Protestants have entered the chat. They now have a political heuristic of their own: Christian nationalism, which is an explicitly Protestant political-theological project (astute Catholics understand this). The rejection of universal papal authority by the Protestant Reformers necessarily limited the scope of church and state to national boundaries. Little recognized by modern American Protestants is that the recovery of the Constantinian ideal—the duty of the magistrate to look after the bodies and souls of those under his care—was an indispensable feature of the Reformation, emphasized repeatedly by 16th- and 17th-century Protestants like Peter Martyr Vermigli, Heinrich Bullinger, Franciscus Junius, Wolfgang Musculus, and Richard Baxter, but now shunned by their theological progeny.

Understood this way, Christian nationalism is a welcome development. Protestants have offered little if any positive political vision for the country ever since the mainline became a handmaiden of post-war liberalism and, ultimately, abdicated national leadership. If for nothing else, Stephen Wolfe deserves our gratitude for firing the first shot across the bow, a shot that has wounded many, been deflected by few, and returned by even fewer.

But what of America?

The extent to which Christian nationalism is socio-politically viable in America depends much on the history of Christianity in America. If America at its inception was properly characterized by something ethnically and religiously specific, then the Christian nationalist project is less aberration and radical transformation than recovery and renewal.

Mike Sabo answers this question with pertinent evidence to demonstrate the colonial and antebellum Christian character of the nation, including formal and informal establishments enshrined in state constitutions. He mentions that most of these establishments were some variety of Protestant, and that vestiges of that culture endured well into the 20th century. This alone will surprise many, but we can say more.

Anti-Popery

America’s secession from Britain was animated by a distinctly Protestant mood. In 1774, the leaders of Suffolk County, Massachusetts drafted a resolution, later endorsed by the Continental Congress, against the Quebec Act, which prompted fury and fear throughout the colonies. They charged “That the late Act of Parliament for establishing the Roman-Catholic religion and the French laws, in that extensive country now called Canada, is dangerous in an extreme degree to the Protestant religion.”

Alexander Hamilton published a lengthy commentary on the Quebec Act, characterizing its “dark designs” as “permanent support of Popery,” effectively transitioning the “Romish Church” from a “state of toleration” in English territories to one of establishment—“an atrocious infraction on the rights of Englishmen.” No true Protestants of “common sense” could support such a measure. Samuel Adams encouraged colonists to zealously guard their religious rights against “POPERY,” and Jonathan Mayhew warned of incursions of “popish idolatry.”

On both sides of the Atlantic, George III was denounced as a “popish king” in the wake of the Quebec Act; imagery of the Gunpowder Plot (1605) was regularly invoked. The act was “high treason,” and some colonial papers even insinuated that it would usher in a “Gallican constitution” that would replace colonial charters. Popery was made synonymous with tyranny and arbitrary rule, and antithetical to the English constitution wherein the monarch was head of the Protestant church. Indeed, the late Forrest McDonald suggested in his Novus Ordo Seclorum that at the popular level, fear of widespread anti-Catholic conspiracies, of which the Quebec Act was supposedly part, was perhaps the animating factor in the American revolt.

What was this but, to paraphrase Wolfe, a particular Christian people acting self-consciously as Christians for both their “earthly and heavenly good”? What explains this fear and prejudice but a Protestant land conditioned by Protestant sensibilities, stigmas, and conspiracies? Where else would “Pope Night” (i.e., Guy Fawkes Day) be celebrated for centuries other than an English Protestant country?

Nursing Fathers

Yet colonial Protestant outrage was not motivated simply by anti-papal animus, but rather a deeper conception and expectation of Protestant kingship, of the relationship between the magistrate and the ministers, between state and church—political assumptions imbedded deep in the colonial psyche that would leave a deep impression on the later United States, which have been too often ignored by modern interpreters of the pre-revolutionary period.

One of the most controversial aspects of Wolfe’s book is his chapter on the Christian prince. Protestants and non-Protestants alike have instinctively recoiled from it.

As I’ve shown elsewhere, the ideal of the reformist Christian magistrate, the “nursing father,” is entirely indigenous to the Protestant tradition. Taken from Isaiah 49:23, that formulation is readily available in post-Reformation Protestant theologians such as Vermigli, Bullinger, John Calvin, Johannes Wollebius, Francis Turretin, and Samuel Rutherford to name a few. More importantly, it’s explicitly taught in confessions like Westminster, Savoy, the Thirty-Nine Articles, the Irish Articles, the Helvetic Confessions, and so on. Throughout the tradition, and until very recently, the Christian ruler was expected to exercise a religious interest, to punish notorious public sins like blasphemy—and to protect, indeed encourage, true religion. Franciscus Junius charges the magistrate to assist “his society in aspiring to the gate of eternal salvation.”

And yet, again, the question is, what of America? For a more indigenous example, see the Cambridge Platform—the confession that would have governed the churches where Franklin, Adams, Hancock, and anyone else from Congregationalist New England grew up—which casts the magistrate as Nehemiah. It teaches that “Magistrates are nursing fathers and nursing mothers, and stand charged with the custody of both Tables [of the Decalogue].” The Platform adds that civil authority is not only concerned with providing “the quiet and peaceable life of the subject in matters of righteousness and honesty, but also in matters of godliness.”

A forgotten feature of the American founding, as James Hutson refers to it, is the endurance of this magisterial conception. (Eric Nelson too has demonstrated the pervasive appeals to monarchical theories of representation by the colonists.)

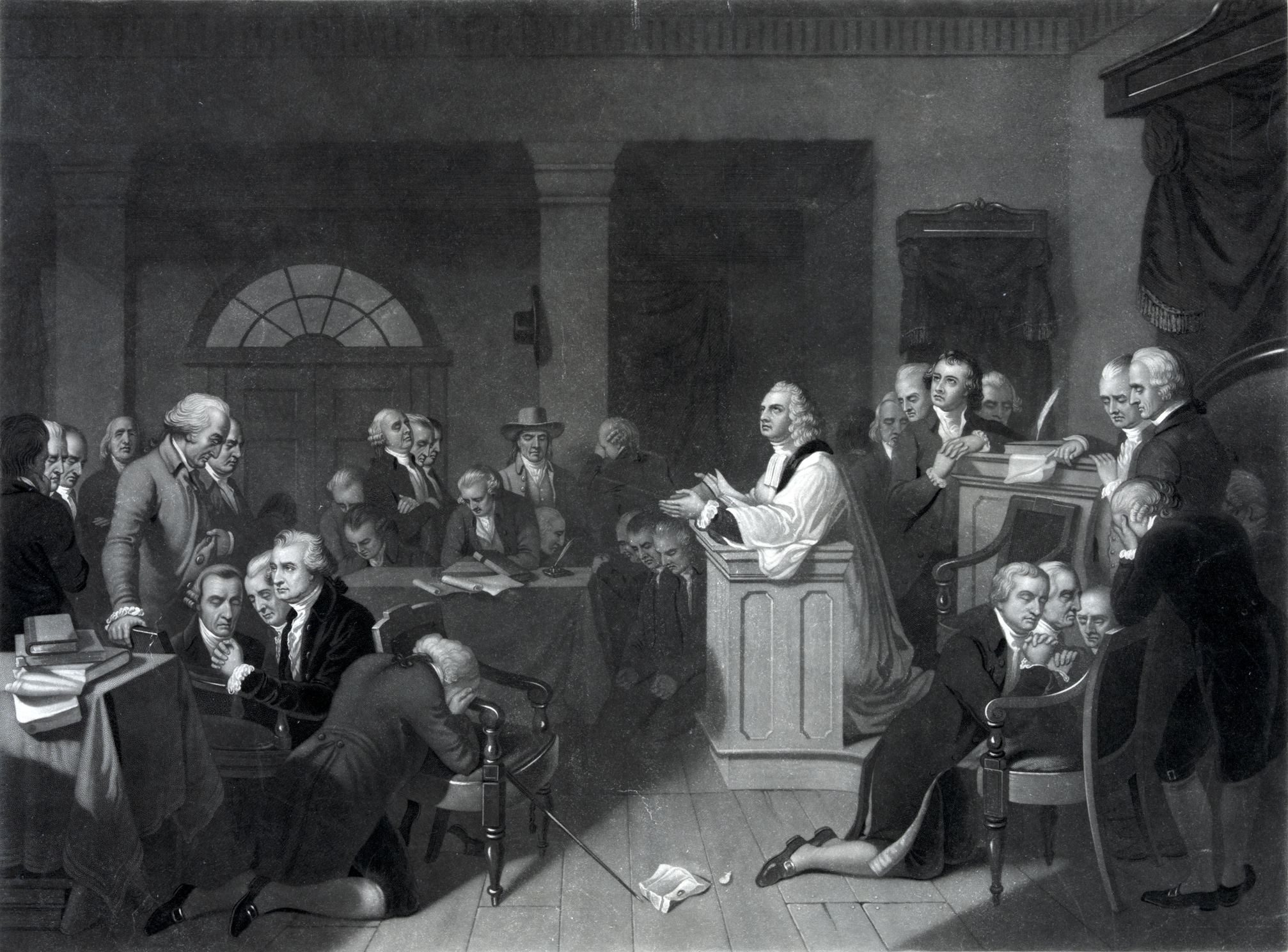

Per Hutson, American Presbyterians like John Witherspoon invoked the “nursing fathers” metaphor, which was a “central concept of New England Congregationalists.” But, in the eighteenth century, this language was not limited just to preachers.

Just four days before Lexington and Concord erupted, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress declared, “as Men and Christians,” a fast day. The accompanying proclamation charged the royal authority (the “Parent State”), which “should be a Nursing Father,” with harassing the established Congregationalist Church, becoming “its Persecutors.”

Church and State

Wrapped up in this prevailing idea of Protestant kingship is the relationship between church and state—that is, religious establishment.

On this topic, as Sabo knows, we find in the historical record decidedly Protestant states composing the American nation—a federalist, pan-Protestant ecumenism, something more than the mid-20th-century sophistry that erected that famous “wall of separation” out of hollow dicta. These little colonial nations, strung together in a sort of new Augsburg Peace (1555), featured laws for office holding, public decency and worship, blasphemy, and the Sabbath. The necessity of a shared public moral orthodoxy to inform law and policy, and indeed the national ethos, was an assumption that governed both Tidewater Virginia as well as mountainous New Hampshire.

Again, we see this legal testimony inter alia in America’s states from its early requirements for office. New Jersey qualified religious liberty to mean that “no Protestant inhabitant of this Colony shall be denied the enjoyment of any civil right, merely on account of his religious principles.” Massachusetts limited public funding for ministers to “the support and maintenance of public protestant teachers of piety, religion, and morality,” even as protection of law was afforded to all Christians. South Carolina declared itself Protestant. North Carolina, Georgia, New Hampshire, and Vermont required office holders to be Protestant.

Commentators on all sides of the ratification debate recognized that America was a Protestant nation fit only to be ruled by Protestants. None of this denied a certain liberality within nigh unprecedented homogeneity. Therein, dissenters could be tolerated, which was not to admit them to socio-political leadership which was assumed by Protestants. Quite simply, in the early republic up through the 19th century, Protestantism was coded into the very DNA of religious discourse.

Robert Handy records that even in post-disestablishment America—the history of which was winding and complicated—the “Belief that a society needed a unifying religious perspective and a broadly accepted morality continued.” And that belief was, in fact, shared by “many of those who contributed to disestablishment,” that is, deconstruction of parish taxes, religious tests, and the like. All things considered, the scope of a new American Christian civilization throughout the first half of the 19th century remained limited to a clique of Protestant denominations. Even by the late 19th century, Princeton’s Charles Hodge could still maintain that it was simply a “statement of a fact” that America was a “Protestant nation,” as demonstrated by its institutions, laws, and “organic life.”

Anti-Protestant Histories

That America at its founding was distinctly Protestant should not be news. But it is too easily and typically ignored in favor of narratives more conducive to contemporary needs. In turn, said narratives are weaponized to stifle political imagination by limiting the range of historic continuity. Too often so-called conservative historians and political theorists have aided and abetted this maneuver.

You will hear of the Lockean founding, or of the more general Enlightenment founding, and, for the more bold, the Christian-influenced founding. Rarely do you hear of any explicitly Protestant founding. Protestantism has been sidelined as the socio-political glue of early America.

As Grant Havers has rightly noted, Straussians like Michael Zuckert and Thomas Pangle, in particular, also shun the American Protestant ethos even as they inordinately elevate Locke—himself a Protestant, if a Socinian—and questionably interpret him as a secularist. Never mind that Locke himself had no tolerance for atheists, or that Milton, Hobbes, and other “influences” on the founding generation considered both atheists and Catholics beyond the pale. Never mind, also, that the Puritan stalwart John Owen was Locke’s dean and tutor during his time at Oxford and that Locke himself was of Puritan stock. Locke may have had a penchant for the Epicurean, but he still occupied and, in many ways, expressed the Protestant milieu that endured through the American founding.

Barry Alan Shain has offered perhaps the most forceful corrective to this oversight. In the 18th century, the American “vision of the good,” the “core understanding of human flourishing” both political and social, was not “secular and individualistic” but rather “reformed Protestant and communal.” That is, the “localist and communal” outlook of the founding generation—an illiberal outlook—was owed to Protestantism as much as republicanism, and certainly more than “modern rationalism,” the influence of which was concentrated in “progressive elite” circles.

When others such as Gregg Frazer account for religion in America’s formation, it is diluted to the supposed “theistic rationalism” of four or five household names (i.e., “the key Founders”), the same method and scope preferred by most progressive scholars. Alan Gibson has charted the contours of interpretative debate surrounding the founding. Conspicuously absent from the litany of interpretive camps is Protestantism.

True enough, many learned elite theorists cited Locke, Montesquieu, Burlamaqui, and so forth. But none were engrained in the American mind, none weaved sinews across ideological divides as Protestantism did. Dalton’s Country Justice and Blackstone’s Commentaries were common, to be sure, but more thoroughly influential texts on the American mind were Calvin’s Institutes, Rutherford’s Lex Rex, the Westminster Catechism, and the King James Bible, not to mention the mountain of local sermons preached by Congregationalist and Presbyterian ministers. These saturated colonial American households wherein, per John Adams, the American revolution predated war and formal codification. And what unites the various key figures of the founding, from Roger Sherman to Samuel Adams to James Wilson to John Witherspoon, is the theological-intellectual-cultural conditioning of Protestantism, which is true even of the less devout founders like Benjamin Franklin, the more private like George Washington, the late bloomers like Alexander Hamilton, and the more heterodox like John Adams.

None of them—nor the country itself—can be understood without taking Protestantism seriously, nor will any continuity between them be recognized absent the same. Christian nationalism at its best, and as an overdue Protestant effort, seeks to revive this historic and political self-consciousness.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

It’s far more than the latest ad hoc term for everything the regime despises.

It takes more than online wishcasting to win elections.

Some labels are just about chasing normal people out of the polite mainstream.

A time for choosing.

Neither liberal theologians nor online anons offer a plausible way forward.