Part II: Honor and self-constraint can stave off tyranny.

Between Suicide and Murder, Part Two

The conclusion of a report from the Southern border.

The American Mind is pleased to present the second half of an exclusive report from both sides of the Southern border. You can read part one here.

I regretted not having downloaded music for my drive across West Texas. It would have been nice to listen to songs with sustained notes to complement the expansive landscape. I was instead stuck flipping back and forth on the car stereo between a radio evangelist and a NPR host. They both moralized in the same way, which, over hours, mesmerized me into a kind of political schizophrenia. Because daytime temperatures around here are regularly over 100 degrees, the roads were lined with blown out tires, which gave a distinct burnt rubber smell that for me became Texas perfume. Whenever I pulled over for relief, my piss seemed to almost sizzle and vaporize on contact with the asphalt, like water boiling over on a hot stovetop. The highways ran straight in the desert for hours. I had to stare into the heat haze distance which made my eyes cross unless I readjusted constantly. Even while driving 130 mph in my rental car I was still bored.

The inescapable presence of obesity in this part of America is hard to overstate. When I arrived in Texas, I chose to eat barbecue in El Paso for my only meal in over 24 hours. At the restaurant, I lost my appetite on first sight. Without any joy the clientele swallowed massive portions, as though any chewing or tasting were the mere inconveniences of food.

I would have recovered had this been only an unlucky encounter but, on the contrary, much further exploration showed the entire population in this region of America to be comprehensively, terminally fat. As with the apocryphal story of the child being dragged into the cancer ward by parents who have discovered their son’s smoking habit, I might one day bring my future (hypothetical) daughter to southwest Texas if she ever started over-eating: “This,” I would tell her, pointing indiscriminately at anyone South of San Antonio, “could happen to you too if you don’t stop it.”

Driving across this great state for over 1,000 miles, I was reminded of this enduring tragedy even by innocent-seeming inanimate objects: in restaurants, the plates were oval to accommodate more food; in restrooms, the toilets flushed torrents to handle larger receptions; everywhere, the chairs were fortified to buttress heavier bodyweight. Sometimes wishful thinking led to mirages. More than once I was gullibly enticed into many saloons by their well-attended parking lots, expecting cowboys inside, only to leave having discovered something worse than cattle. At least tame gentle cows have curiosity and desire in their eyes compared to the average obese Texan who, pathetically, lacks even animal vigor.

It seemed futile to ask such people what they thought of the wall and their national security. How could people so neglectful in preserving their own physical limits care about the country’s border? After all, the nation properly understood is an extension of its people. I recalled this fact whenever I was near any international junction.

And so I drove excitedly into desert towns with fantasies of Texan vitality that were summarily dispelled.

The mining district of Terlingua has a reputation for attracting eccentrics, and I was told by everyone along the way that I would have no trouble meeting interesting “weirdos” there. But I only found artists with alcoholism, weed addictions, and perfectly orthodox views. Within a few minutes of conversation with any given “weirdo” interlocutor, I had enough information to predict his every subsequent opinion. Is this what passed for “interesting” around here?

Even in the town of Alpine, which came highly recommend for its traditional cowboy culture, all I found was a mocking outward simulation of the Wild West on its main road. The cafés and bars with the quaintest “authentic” Western names invariably featured the most up-to-date variation of the Pride Flag on their storefront window. In Marfa, a desert city that has become famous for the installations of the minimalist artist Donald Judd (1928-1994), whose art has no “compositional hierarchy” and was constructed self-consciously to escape definitions, I stood in a parched field looking at grey concrete blocks after having been instructed to “examine my own subjectivity” in their presence.

What I gathered from locals about Marfa’s reputation was that the town is really something of a giant sandbox where fashionable types come to cross-dress in country-western outfits. While speaking with a boutique owner, who sold $1,000 ponchos and $12,000 leather jackets, I was told that Marfa is very popular among Californians and Chinese tourists, who mainly come to take pictures of themselves in front of the fake Prada store. The proprietor too was from elsewhere (Austin) and once we got on the topic, he confessed to me that he didn’t believe that migration could ever be illegal anyway. What’s more, he thought that everyone in search of a better life was welcome. But he also let slip that he was partly Mexican and that his heritage made the issue a personal one.

An interesting confession indeed: in his confused biology there were stronger loyalties than all the attempts since birth to inculcate him with the Pledge of Allegiance, and all the other feelings of patriotic American pride, to the point where he was willing to dispense with the borders altogether. I could have argued with him to amuse myself. But how does one sincerely fight ideas like this when they have been born deep in the blood?

Despite what city people like to think, rural communities are rarely bastions of resistance against “progressive values.” In fact, you will find their most enthusiastic supporters in those places. Every posturing small-town Main Street contradicts the wholly inaccurate notion prevailing among nostalgic conservatives who insist that the countryside has dutifully preserved tradition while city-dwellers have faltered into godless decadence.

If you are confused by the idea of a “backwoods liberal,” or think that it is somehow a contradiction in terms, all you need to do is observe any “rustic” woman. Though physically far away from glittering luxury, women in farmhouses have the same access to modern culture as every urban female (whom they cannot but envy as their superiors). Not only do they emulate what they see on television or on their phones, they have the added insecurity that comes with their “provincial” origin, and they try to compensate for it desperately.

It can be hard to find the exceptions.

I met Shelly. The mock Prada store was built on her land. What was more bizarre than the art itself (which, like so many other trite “commentaries” of this type, justifies its existence to itself purely by its own irony) were all the visitors who treated the piece like some incredible monument. Shelly comes from Valentine, where she is one in a total population of 73. For six generations her family has raised and wrangled cows there. The men in her family are among the only genuine cowboys left in West Texas. She assured me that her daughter is even better on a horse, with videos as proof.

The family is constantly dealing with migrants on their 75,000-acre ranch. Sometimes as desiccated corpses: these are the migrants who die after several days of walking in the heat without water. More frequently they find migrants close to death limping along with blistered feet or in poisoned languor from rattle snake bites. On more than one occasion they have found smugglers resting under Mesquite trees.

There is something no doubt impressive about the hardiness of migrants who cross the border where there’s nothing on the other side but life denying desert. But their determination also raises the question: why cross here when most other places are easier?

Among the very few good reasons I’ve heard is that some have criminal records and will risk death over capture. But what I noticed is that most migrants travel in total ignorance. I would ask them, whenever I could: “Why cross here?” They could never provide a compelling answer. Very few used satellite-based navigation (except for the ones who were drug mules) and none seemed to take advantage of the many available online resources, including one website which has mapped out the entire American-Mexican border with clearly-indicated walls, fences, and opportune gaps.

Shelly told me that most migrants who walk from Mexico into Valentine lose power on their phones early into the desert and so have printed out pictures of landmarks—mountains and trees and houses—as beacons toward their illusions of a better life. Even at the most common places of entry, such as in Eagle Pass and El Paso, the migrants never seemed to have any detailed plan or strategy. Most weekend campers and amateur hikers are better prepared in comparison. The migrants instead yield to the herdlike instinct of looking ahead to see who succeeds or fails, and following those who make it through.

Shelly told me about all the troubles she had experienced on her land. I could have listed them here for you, but more revealing than the issues faced by ranchers like her was her overall defeated countenance. I had seen the same face before in the West Bank and other war-torn territories where Arabs bore the mark of total loss and hopelessness.

The romantic West Texas cowboy appeared to me as equally tragic, but in a different way. Perhaps he is fated so in part because of his fidelity to the stark and brutal mountains that emanate a beautiful melancholy. Or maybe it’s that the cowboy is simply an offshoot in history, and shares the risk of extinction like other traditional people who live against time. What’s obvious is that the cowboy is really a libertarian, in the proper sense of the word, in that he does not want to impose his opinion on others and refuses the constraints of the social community. What this means for him, unfortunately, is that he is someone who supports the freedom of his enemies, who deny him the same.

The cowboys I’ve met are harrowed by the change in their towns and the loss of their culture. But even while wounded and angry, the cowboy seems against getting dirty in the realm of politics. He is unwilling to wrangle lies on the terrain where words reign supreme. Like the noble hermit, he only knows how to retreat further into the wilderness and focus on the demands of the ranch, which he masters in solitude, unlike the lowly peasant, until he too is claimed by the land on which his cattle graze. This is the charm of the cowboy and ultimately his destruction. Hence the tragedy, to which he is not blind either. His fate is both acknowledged and expressed in the country music that, marked by the deep coarse groan and the pluck of the whimpering guitar string, are the heart-aching eulogies of his ruined world.

What will be left after are the fictional versions, like those in Marfa, who, already outnumbering the real cowboys, will claim and distort the legacy of the frontier American.

What is there to learn?

Nature is immodest in her preferences: the future only belongs to those who fight—and win.

***

In Ciudad Juárez, just on the other side of the border from El Paso, I found more of the authentic Wild West than I saw anywhere in Texas. The bars had Mexican cartel members, Russian mobsters, Italian mafia, Haitian hucksters, and many other criminals of every prison stripe. Some men had recently been deported from America and sat alone with the tortured dilemma of whether to return illegally through the fence or go back into some impoverished village deep in Mexico. There were even native-born Americans here who were genuine outlaws and who stayed within the border city. Maybe because they had only just arrived, or maybe because the proximity to El Paso assuaged their sense of homesickness. Regardless of their backstories, everyone was interesting, and unlike in Terlingua, Texas, no one was predictable. I drank with men with whom I shared the only redeemable version of small talk—when there is personal danger from probing too much. I met one man named Tony who spoke English and worked in the stockyards besides the international bridge. He spoke freely about his good standing with border security and hinted at his cartel connections. His relationship was an obvious asset, because he was never searched or questioned by custom officers. After convincing Tony of my own twisted sense of adventure I was able to persuade him to take me to a bar where killers drank.

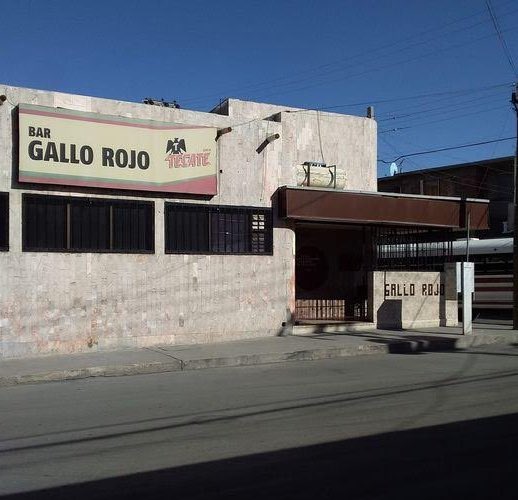

I entered Gallo Rojo less gingerly than recommended from the liquid courage that became liquid indifference after a few more drinks. Within the rectangular bar were four women abusing their ankles in high heels. The bartenders were also—unimaginably—prostitutes. They were so fat that the only way a butcher could have distinguished their thighs from their rumps would have been from the underwear seams, which were all too visibly squashed between the whores’ expansive flesh and their tight dresses. I bought a one-quart bottle of beer, the neck of which the bartender stuffed with a napkin (a gesture to show nothing stronger had been slipped in) who then pinched my cheek lasciviously. Usually in the company of very hard men, I regress into feeling like a boy. Here was no different. But the masculine wench had grabbed my face so forcefully that I also felt myself made—“transitioned” maybe—into a woman. Why anyone would pay to spend an hour or an evening with such beasts was beyond my limited empathy. But I could only imagine the confessions that these women had been told on filthy mattresses: they were not only tarts; they were the secret-keepers of this underworld.

Tony told me that the “lowest of the low” drank in this bar, which was famously where the cartel recruited hitmen. Here, one could earn minor prestige, an intimidating reputation, and be renumerated $500 for a single murder. I looked around. No one looked especially dangerous. “That’s what makes them dangerous,” Tony said, undeceiving me.

I had seen obvious gang members, with tattoos on everything but their eyes, who displayed their affiliated bandanas ostentatiously. I had even asked one for his last cigarette. “You were lucky,” thought Tony. These were allegedly the boys who, years ago, played games in traffic by honking their cars at other commuters: if their honks were returned, the driver would be shot and beheaded; if instead the provoked target remained passive and respectful, he would be given some money and informed of his good luck.

Of course, it’s hard to know which stories are true, and which are simply myths. Whatever the facts are, Juárez is certainly dangerous. On the outskirts of the neighborhood of Anapra, the most feared place in the city, a pickup swerved in front of the car ahead of me. I skidded to a stop while three men with rifles disembarked from the truck’s bed. With tactical swiftness and in full-face skull-masks, they pulled out two men from the car and placed them face down in the sand. The gun barrels were then pressed against the backs of their head. Were they killed? I don’t know. Were the armed men police or cartel? It’s a difference without a distinction for most locals. I was only happy that, whoever they were, they waved me along. While in another slum with a horrible reputation and the terrifying name Aztecas, I haggled unsuccessfully for a large white tablecloth on which Our Lady of Guadalupe had been embroidered by hand. Two Dodge Chargers with tinted windows slowed down to investigate my intrusion on their turf. I had with me online screenshots of some nearby restaurant with high ratings and positive reviews, which I had taken for the sole purpose of feigning ignorance, because at times the best way of looking innocent is by looking stupid. I drove away, alive, though regretfully without the linen cloth.

As Tony became more intoxicated, he became more candid. Once, after I returned from the “toilet”—which was only a gutter in the floor against a tile wall (accommodating even my worst aim)—Tony confided in me that his wife would be very upset if she knew his location tonight. Because of the obese puta in her bodycon minidress? “No, because people have been shot in here recently.” And yet, there was no smoking inside the bar because of newly-passed legislation banning the practice. I didn’t try to make sense of it.

More importantly, I wanted to know where I could find higher-ranking cartel members. Tony told me that Japanese sushi restaurants or expensive steakhouses were the most likely places. Never in this neighborhood anyway. The bosses typically drank less in bars and partied more in private homes nearby the country club. Wouldn’t that infuriate all the respectable neighbors? On the contrary: “All the lawyers and doctors are there,” Tony told me, even when such soirées go till the late in morning.

How might I recognize these more esteemed men? “The top bosses are not like me, they have fair skin and blue eyes,” he explained, rubbing his swarthy forearm, “whereas the darker, lower bosses wear jewelry,” to demonstrate their status, “like this one here,” he said pointing towards a sleazy man at the bar.

I had also heard this observation made by my hotel concierge, Fernando. He had driven me to the police station after I received a parking ticket. It was no doubt because my pristine white car stuck out from nearly every other vehicle in town that bore dents, scrapes, scuffs, and lacked entire parts. Since nothing in Juárez is digitally centralized, I would have left without honoring the fine, but the Mexican parking authorities had prepared for absconding visitors and removed my Texas license plates. After I left the police station, I asked Fernando where I could find some drugs. To my misfortune, his dealer had been killed earlier that month. The entrepreneurial ambition of running his own business had meant undercutting the cartel, whose leaders never allow for (other) subterranean networks to form, however elementary and amateur they might be.

Despite this setback, Fernando told me he could find anything from cannabis to crack. “What do you want, brother?” he asked. I told him I wanted fentanyl. Laughing, now aware my questions were strictly academic, he informed me, “That’s only for the USA, brother. You can’t find it in Mexico.” Why? He could only offer theories. Maybe because fentanyl is too dangerous and would destabilize cartel control. Maybe, and by the same logic, fentanyl is Chinese warfare meant to disrupt their geopolitical rival. Whatever the reason, real or speculative, what Fernando implied was that American leadership allows for its own people what the cartel prohibit.

It was late when I left the Gallo Rojo, still with some money in my pocket in case I met the police on my way to the hotel. I would have to bribe them tonight if they caught me driving, Tony warned, drunk as we said goodbye. “So, it’s a good thing I am well practiced,” I told him. I walked out into a sketchy alleyway and thought about my short time visiting all these places on both sides of the border. As brutal as life is here in Mexico, people still want something and they’re willing to get it, whereas in Texas there were no signs of desire or even hope. (An interesting follow-up question is “Why?” since the ethnic differences are so small.) Perhaps in exaggerated terms, I arrived at the provisional conclusion: I would rather live in Juárez, where I would fear murder, than in West Texas, where I would welcome suicide. The truth of which remained in the morning when I was sober—that in Juárez, among the people, there was at least an instinct to live beyond mere existence.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

On campus, today's forlorn meritocrats no longer believe what the apparatchiks are teaching them.