If you don’t have borders, you don’t have a nation.

Between Suicide and Murder, Part One

A report from the Southern border.

The American Mind is pleased to present this exclusive report from both sides of the Southern border. You can read part two here.

The Mexican didn’t even take off his shoes before he waded through the brown waters of the Rio Grande. He was fully clothed as he trudged toward the other side of the riverbank where a breach in the border was visible. When he was once again on dry land, he excitedly skipped around and waved his arms to encourage vocal support from an eager audience. Everyone obligingly cheered and whistled for his success—as these spectators had a common interest. He then gave his farewell salute while slipping through the oval hole in the chain-link fence before disappearing around a dune: another migrant had escaped his geographic womb and entered the land of promise, America.

Or so everyone thought.

The Mexican soon reappeared, desperately sprinting back to Mexico in retreat, his wet back now turned against his anticipated future. Behind him a border patrol truck pursued. The runner’s complete reversal in direction, and his change in demeanor from cocky to terrified, had such a slapstick irony that everyone laughed. The man was laughing too as he dove dramatically back into sovereign Mexico, a needless performance only done for our entertainment. His friends scuttled over with irrepressible classroom giggles and handed him a bottle of cold beer. They jeered and celebrated—approving his courage, mocking his failure—with gestures that could only mean: “Better luck next time, amigo.”

***

There is very little to say about the America-Mexico border that hasn’t been said already. There are more than enough documented facts to enable anyone to form an opinion. Examples of criminality and misery are easy for every kind of politically-motivated observer to reach out and snatch. But I was surprised at the sheer amount of fun people were having on this strip of scorched dirt where the Rio Grande snakes between Juárez and El Paso.

Here border crossing becomes a kind of schoolyard game, most often with a division between those who chase and those who flee. I decided to play the fleeing migrant. I made a very slow and exaggeratedly long step across the state line, which was like the lunge of some kind of Hispanic astronaut. The American patroller moved toward me. For a moment I was in danger of being caught. I recoiled one step. I was safe again. It was silly. It was fun.

It was also hard to determine who was here to cross the border and who was simply here for leisure. In the same water that earned Mexican migrants one of their trademark slurs were children in donuts floating downstream. Many families had set up tables and charcoal barbecues over which freshly net-caught crustaceans were being grilled for lunch. There were lemonade stands and food vendors for the less resourceful.

I approached a man in a crisp dress shirt, a straw brimmed hat, and clean white loafers. He was surveying the area carefully. I assumed he was a professional of some sort who was here to make observations. “I work in a grocery store in Juárez, and I want to cross this week,” Armando told me, in a manner that was both friendly and matter-of-fact. We spoke about the advantages of crossing at this location, and I gave shape to his vague plan for illegal entry with practical questions and helpful suggestions. “This is my eighth attempt at crossing,” Armando said, unashamed, with a chuckle, “and every time I get caught, I end up inside a detention center.” What is that like? “The sandwiches are very good,” he said. Is it not uncomfortable? “It’s like a vacation.” A vacation. So, this particular game has been designed in such a way that there’s nothing to lose and everything to gain.

This isn’t to say there aren’t bad ways to cross as I found out later in my trip. Or places along the border that are harder to navigate. Only a few days before, I was at the crossing between Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras (where Mexicans are not yet anxious about offensive Latin etymologies). At the time there was a lot of collective hysteria over a new string of orange buoys that had been anchored as a floating wall spanning the length of the river to prevent people from crossing into America. The Texas governor had the barrier installed without federal permission. Its critics, from the Mexican president to several American Catholic groups, were liberally using the term “inhumane” whenever asked to comment on the new floats. Meanwhile conservative newspaper columnists were applauding the fact that “something had finally been done” to deter international trespassing.

And yet even this most controversial security initiative, in my eyes, was but another example of silly games being played. Because only Western nations willingly tie their own hands with the restraints of “universalism” and “human rights.” The cartels suffer no such limitation in understanding human psychology in its most honest and denuded form. They do not have to look for loopholes or tricks to achieve their objectives; they know that the most inhumane deterrents are often the most effective ones. But this kind of thinking cannot enter the American imagination. And so, the alternative is what we have now: games.

***

Of course, what makes all this illegal migration so shocking is the continued flagrant violations of the border’s only purpose, which is to maintain state control over who enters the country and who leaves it, and to keep unwanted people out. Of course—until recently, anyway—most migrants actually don’t cross the Rio Grande. They come by airplane and overstay their allotted time. Often, some paperwork can convert an “illegal” immigrant into a “legal” newcomer overnight. Then there is the huge number of legally-imported foreigners who, far more compromising to the American national character, are praised as “model citizens” for lowering labor costs of high-skill work. Still, if anyone with enough determination can illegally infiltrate the country by whim—penetrating without official consent (there is yet another word for this)—that alone sufficiently qualifies America as a “failed state,” even by the loosest definition.

In Eagle Pass, I stood for half an hour at the border watching vehicles go over the bridge. The license plates all came from Texas or Coahuila. Inside the cars everyone I saw was brown, without a single white occupant as an exception.

This national border is very different from the many others I’ve seen where countries use their side of the boundary as a stage for nationalist displays. I was reminded of the Greek border, where facing The Republic of North Macedonia there is a government-official emblazoned Sun of Vergina. Written underneath it in Greek (and translated into English for an added cosmopolitan insult) is the statement of fact: “Macedonia was born Greek.” There was nothing like that here.

Even though you’re still in Texas, when you’re this close to the other side, everything seems to just give up the pretense of being American and becomes Mexican in anticipation. None of the signs above or inside the commercial stores are in English. Nothing inside the shops suggest anything patriotic, or even notionally “American” or obviously Red, White, and Blue in orientation.

I drove to a nearby flea-market that sold Mexican products, at Mexican prices, for Mexican-American customers. It was mostly junk-piles of children’s bicycles (all of them broken), used landscaping tools (such as leaf-blowers, at which I laughed too loudly), new oversized floral dresses (being scrutinized by commensurately oversized women), and some delicious tacos (of which I ate so many even the oversized women became impressed).

From the market I walked across a huge, perfectly mowed lawn and made my way toward the river, where the border “wall” was really made up of double stacked shipping containers, some them communist-red and labelled in capital letters: “CHINA.” The lack of national self-respect and concern for self-image seemed to say a lot about the current state of America.

I realized that the grassy buffer zone was also a golf course. Next to me, under the bridge that crossed the river, the border security had parked their cars strategically in the shade, not to survey the area for prevaricating migrants, but for themselves to evade the summer heat. Over here everyone was hiding from something: the patrollers from the sun, and the migrants from both the sun and the patrollers. Before I could get too far I was intercepted by the Texas Highway Patrol, who interrogated me. “I am trying to sneak into Mexico for more opportunities and a better life,” I told the officer. He gave a generous laugh and then warned me that, no, neither the public nor the media were allowed any farther—that I was already in violation of the law. “What if I got a day pass at the golf course?” I asked, pointing out that the green was manicured right up to the river. He thought about it. If I did that, then I would be free to roam where I pleased.

Of course, no day passes were required to look at the scene from the Mexican side, so I drove into Piedras Negras and walked along the water. In Mexico, the area facing the river and the American side has been developed cosmetically to look almost like a resort town. A naïve observer might think that people were trying to get onto this side, and not the other way around. Except no one was here. There were barren stone benches facing the water. The swings were still, and the monkey bars in the several playgrounds had no children playing on them.

It would have been very quiet if it were not for the repeated pre-recorded warnings intended for any migrants who might be thinking of swimming across to the American side. The announcements came from the golf course, from speakers perched high on a pole. There were also signs to prohibit swimming and one warning about alligators, which I never saw, and assumed was only to discourage people from getting in the water.

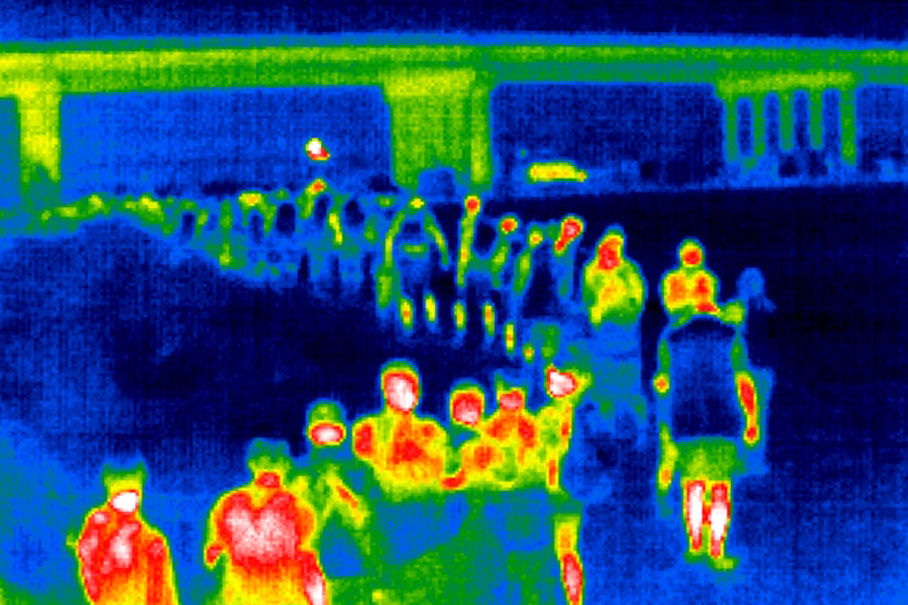

I drove my car east outside the city of Piedras Negras. At some point, the freight container wall turned into coiled-up steel-strands with punctuating razor blades—“concertina wire” it’s called technically (which rolls off the tongue sounding just a little too elegant). There is very little structural security besides the large strobe lights that shine on migrants who pass over the border at night, when they prefer to travel. Every few hundred feet, a parked armored Hummer kept the engine idling so the occupants could enjoy the air conditioning. These patrollers served either for the Texas Department of Public Security or the Texas Military Department. They were here for “Operation Lone Star” in tan uniforms, which distinguishes them from the green-donning Border Security officers. One reporter told me: the tan men prevented people from crossing the border; the green men helped foreigners to immigration services. Be assured that such distinctions are quickly learned by migrants. The tan patrollers on American soil watched me intently. I walked along the river where burned-out tree stumps had contained recent campfires. They were surrounded by garbage, including crushed beer cans and littered clothes, and the odd rubber sandal. I looked back at the men on duty. There was no security here on the Mexican side. Instead, there was only a very good horse.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Socialists face setbacks across the globe, and Joe Biden could be next.

The country is now filled with people who chant for its death.

When a nation refuses to guarantee the personal safety of its legislators, its politics are a sham.

The woke iconoclasts come for Texas history—and Texas fights back.

Sane Texans must act to remove all traces of DEI in the state.