Despite hostility from the Biden Administration, the report stands as a guiding light for future generations.

Something to Say to the Sphinx

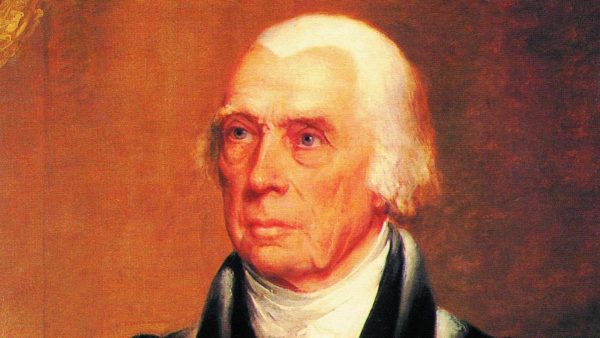

Remarks on James Madison’s vision for the Country

These remarks were delivered at the Claremont Institute Alumni Retreat and Salvatori Dinner on November 16, 2019, where Professor Sheehan received the Salvatori Award.—Eds.

Thank you so much, Ryan. And thank you to the folks at the Claremont Institute and the Claremont Institute Board for this kind and deeply appreciated honor. Thanks especially to Tom Klingenstein, John Eastman, Charles Kesler, Matt Peterson, and Amanda Callahan. Thanks also to my daughter and good friends who have joined us this evening, Brenda Hafera, Bill and Carol Allen, Laura and Jeff Wallin, Henry Olsen and his fiancé, Audrey. I am grateful to the exceptional scholars and teachers I had the good fortune to study with during my years at Claremont, Bill Allen, Harry Jaffa, and Bill Rood. And may we remember, not with sadness but with joy—for that would surely be his wish—the life of the inimitable, brilliant, charming, and truly generous soul, Michael Uhlmann.

Ryan asked me to talk this evening about James Madison’s vision for America and how he might confront the looming crisis of our time. The second part I can only guess at, of course, but I’ll give it a go. I’ll conclude with remarks about Robert Frost and his ideas, since he was a reader and great admirer of James Madison, and in fact, named Madison the best dreamer of the American dream.

The story of America is the story of the land of good fortune. Nature gave the nascent country everything. Good soil, an expansive territory, natural borders, a gentle climate, and some pretty good folk. As Washington remarked at the close of the Revolutionary War, just as they were about to move from combat to constructing a nation, America was born in the age when “the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined” than at any previous time in history, and the treasury of collected “knowledge, acquired by the labors of Philosophers, Sages and Legislatures….[was] laid open for our use.” If the citizens of America “should not be completely free and happy,” Washington counseled, “the fault will be entirely their own.”

Today the borders of the United States span from sea to sea. Her population has increased a hundred-fold, the education provided her citizens is ranked in the highest percentile among nations, and she is one of the richest countries in the world. The Constitution has lasted through the ages, and she is the longest living republic that has ever existed on earth.

But still, there is trouble in River City. Or to mix metaphors, there is something rotten in Denver and Bismarck. Americans are unhappier than they’ve been in years and they’re angrier than they’ve been in a while—especially about politics. They don’t like the government and they don’t much like each other. We are a fractured and disunited nation, split for the most part into two ideological camps, each side persuaded that the other side will ruin the country. Among some Americans there is even talk of separation and succession. “Look, we had a good run,” Bonnie Kristian writes in The Week, “These United States were a grand experiment. But the experiment has gotten out of hand. It’s time to peacefully dissolve the union.”

What happened? What happened to this nation so favored by Providence and Nature? To quote Bertie Wooster allegedly quoting Shakespeare, “It’s always just when a [fellow] is feeling particularly…braced with things in general that Fate sneaks up behind him with a bit of lead piping.” Or perhaps the situation is summed up in the gloomy expression you get these days when you ask an American how things are going. To quote Wodehouse again: it’s the kind of “somber nod…Napoleon might have given if somebody had met him in 1812, and said, ‘So you’re back from Moscow, eh?’”

It might as well be said straight up that things are pretty bad today. But maybe we can find a bit of solace in the fact that we aren’t the first country to be in the soup, and, every once in a while, some of them have managed to find their way out of it and back onto dry land.

The How and the What

From a Madisonian perspective, I think the problems facing the nation today can be clustered into two categories. First, the procedural issues, and second, the substantive issues—or the how and the what problems. The how concerns the way in which we achieve public decisions today: do we still have the necessary institutions and procedures in place to “refine and enlarge the public views”? The what problem results from the fact that the two critical camps in the United States today disagree fundamentally on what the nation stands for or ought to stand for. Is there any possible point of reconciliation that could bring these divergent views into harmony, at least into stable equilibrium?

I’m sure everyone in this room is familiar with Madison’s proffered solution to the problem of faction. The interpretation I’d like to present, though, puts the emphasis on the processes of political communication and the formation of public opinion, rather than simply on shrewd institutional and circumstantial arrangements. In essence, small republics are susceptible to the problem of faction due to the ease and rapidity of communicating opinions, including factious opinions. By contrast, in a large territory, in addition to the presence of a greater number and variety of interests and religious sects, the intersection of space and time substantially reduces the chances that a majority faction will form.

That is to say, the factor of physical space influences the time and momentum required to communicate and unite the public views, which either frustrates the attempts or slows down the process of public decision-making, thereby weeding out narrow, factious views. Madison added to the influences of size and diversification a third factor contributing to the unlikelihood of majority faction forming, that is, the influence of shame. In a territory with a large population, it is less likely that a majority will form on the basis of dishonorable purposes. This is because intentionally dishonest types tend not to trust a very wide circle of people and so eschew bringing many others in on their malicious schemes.

Now, the hurdles that slow down the communication of opinions, while intended to cull factious views from the mix, are not meant to thwart all political communication. These stopgaps also have a positive role in Madison’s design. They buy time, allowing for the work of deliberation to occur. As Madison argued in the National Gazette, the deliberative process includes discussion and debate among representatives in Congress, between the two houses of Congress, and that involving the people themselves—via interaction with their elected representatives, by the influence of the literati, and by means of newspapers circulating throughout the entire body politic. Thus for Madison communication is a double-edged sword; the communication of factious views is, as much as possible, thwarted or rendered ineffective, while the commerce of ideas is promoted and encouraged, resulting ultimately in “the reason of the public.”

But this clever solution to the age-old problem of majority faction is in some important respects outmoded and ineffective today. The world has changed a great deal since the Founding era, and one major difference from their time to ours concerns the revolution in communications technology. The speed and ease of communication, not to mention the more and more sophisticated modes of communication, have proliferated beyond the wildest imagination of the Founding generation. The internet, email, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have, in effect, made the world a smaller place. Although the United States has substantially expanded in territorial size and in population since the 18th century, the effect of these factors has not kept pace with that of the velocity of communication. In other words, in regard to the space and time axis that Madison envisioned as part of the remedy to counteract the formation of majority faction, the element of space no longer has the adequate effect on that of time.

Faction in the Digital World

Today it is exceedingly easy for people to communicate ill-considered, prejudicial, inflammatory opinions swiftly and widely. We are all too familiar with this phenomenon and the harm it can do. In the social lives of teenagers, and especially the increase in depression, anxiety, and suicide among American girls, as Jonathan Haidt has demonstrated, the new communications technology has been nothing short of devastating for too many American youth. In politics, it is bad enough that so many of the nation’s citizens engage in malicious messaging and tweets directed against each other (or that they unfriend one another when they disagree). But the nation’s enemies, as well as “bots,” are also having a heyday influencing politics via social media.

Accordingly, we have to ask whether communications technology has re-created the problem Madison believed he had once solved. Is the large republic now just as susceptible to the disease of faction as the small republic?

While the revolution in communications technology has altered the way in which we must treat the problem of faction, it hasn’t changed the existence of a multiplicity of interests and religions in the United States, and in fact, the nation is even more diverse now than it was two centuries ago. Despite this diversification, though, there does exist a binary grouping in the country along partisan and ideological grounds. This split is so serious that some have claimed that we are now “two Americas.” So instead of the traditional binary opposition between rich and poor that characterized the world for centuries, and which Madison sought to replace with diversification, the battle today is again largely a bipartite rivalry, though this time between an urban, coastal upper class and a more rural middle America.

What about Madison’s third element contributing to the impediment of majority faction, i.e., the influence of shame and distrust on the spread of consciously dishonorable purposes? Here we are faced with more than a change in how the process operates, because the object of shame in our time is very different than that of the 18th century. In addition to the anonymous nature of much social and political media blogging and tweeting, which certainly diminishes the deterrent effect of shame in spreading nefarious views, the idea of honor is no longer the standard by which a large section of the society evaluates human actions. Instead, shaming is thought to be the appropriate response to others who are not on board with the egalitarianism of the social justice movement, that is, those who are not “woke.”

The contemporary challenge of reclaiming the processes of deliberative republicanism is a stiff one. Short of extending the republic beyond the bounds of the earth, thereby regenerating Madison’s space-time axis, it would seem that we will have to depend on institutional arrangements and legal restraints by adding new or reinvigorating old prudential devices (for example, reviving the practice of federalism, or establishing legal restraints on anonymous tweeting, blogging and botting). But even these methods of improving the process of republican decision-making seem hardly an effective patch for such a large hole in the political bucket.

The central problem of our time is that the divide in the nation today is not merely a policy difference, but a core philosophical disagreement about what it means to be human and how we should live our lives. It is the kind of rivalry characteristic of a regime flirting with destruction. While there have been a number of critical periods throughout the life of the American polity, there has, I think, only been one such riven and raw political conflict in the United States prior to our current predicament, and that of course was the crisis faced by the nation in the 1860s. What is different about the two crises, however, is that in the 1860s the battle was about who is human, while today it is over what it means to be human. In this sense, the predicament of our day is even more radically problematical.

The Absolute Truth

In the pages of the Claremont Review of Books Tom Klingenstein has recently argued that “the American way to live…is predicated on the belief, expressed in the Declaration, that there is a universal right and wrong, justice and injustice. It is this that [conservatives seek to preserve and that] multiculturalis[ts and leftists] seek…to destroy.” In contrast to the natural law teaching of the Declaration is the notion of “loyalty to [one’s] identity group or hatred of the oppressive ‘other,’” i.e., privileged, white cis-gendered males who have for centuries conspired against the non-privileged common people.

Conversely MSNBC has created a new “joy market” branding ad, which is a high-budget, symphony-backed, feel-good 60-second spot about America as a work in progress. The message is that we are still working on fulfilling the promise of equality to all people and all identity groups, especially the marginalized, presumably including women, blacks, gays, and non-cis and transgender people. MSNBC’s celebration of the values of the Declaration of Independence mirrors the agenda of the Center for American Progress, which claims that “the United States was created to fulfill a promise of free and equal political life for all of its citizens. [Progressives have]…focused on bringing these core founding values into reality for all people.”

Some progressives, like Sally Kohn in The Opposite of Hate (2018), say that rather than hate each other, we should celebrate our different opinions and perspectives. But how is this possible, really? The celebration of the one is the rejection of the other. Now, it might make sense sometimes to avoid such issues in polite company—like Mark Twain did when he was asked to chime in on a debate about heaven and hell, and he responded, “I don’t like to commit myself, you see, I have friends in both places.” So, while it might sometimes be prudent to remain non-committal, no citizen can dodge the debate indefinitely.

For my own part, I do not see a way forward that rejects the idea of a standard maxim higher than individual will or group desires. Nor do I see a way to compromise the principles of the Declaration of Independence. While obviously I cannot know Madison’s mind on this subject today, I think we can be quite confident that he would judge that an American republic which abandons the central teaching of the Declaration of Independence is no republic at all. He said as much in Federalist 39. The fundamental principles of the Revolution are the stuff that the American genius is made of. These ideas animate “every votary of freedom, to rest all our political experiments on the capacity of mankind for self-government.”

In his 1792 essay “Republican Distribution of Citizens”—a title reminiscent of the classical concern for the occupations, way of life, and character of a polity’s citizens—Madison called upon the statesman to take as his guide the model of the best republic, which promotes safety, liberty, health, economic competency, virtue and intelligence in the great body of the people. In this same piece he clarified what he meant by virtue, defining it as “the health of the soul.”

For Madison the central challenge of free government was to make power and right synonymous in republican government. The difficult challenge of placing the power of the majority on the side of natural right was the great object to which he dedicated his lifelong labors as a scholar and a statesman. It was the same challenge that would face and occupy the mind and energies of another great American thinker and statesman about a half century later, Abraham Lincoln. It is, in fact, the same challenge we always face in America, or abroad, or anywhere there is a people whose aspiration is to govern themselves.

Standing on the floor on the Pennsylvania State House in the First Congress of the United States, as he introduced the Bill of Rights, Madison recalled the central truth that mandates the experiment in self-government. In so doing, he reminded his listeners that the truth that “All men are created equal” in our Declaration of Independence is an “absolute truth.”

On the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Calvin Coolidge repeated Madison’s sentiments. “About the Declaration there is a finality that is exceedingly restful,” Coolidge said.

It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning can not be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions.

Jefferson’s Hard Mystery

Like Coolidge, Robert Frost was concerned about changing the words and ideas of the Declaration of Independence in the name of progress. For Frost there was both a finality and a mystery in the words of the Declaration of Independence. But Frost liked mysteries and riddles; he liked to say, “You’ve got to have something to say to the Sphinx.” “You’ve got to handle these things…handle whatever turns up.” “You’ve got to have something to say….” In one of his talks Frost recounted the story of a Swede the government hired to come to the U.S. to give expert opinion on our form of government. After he passed judgment on the country, we invited him back and gave him an honorary degree. Do you know what his expert judgment was, Frost asked. “That our form of government is a conspiracy against the common man.” Now, “You’ve been enlarged and broadened to where you can listen to anything without getting mad,” Frost told his audience. “But I have to have something to say to that, sooner or later….”

One of the things he said to it, I think, can be found in his poem, “The Black Cottage.” This poetic vignette is about a minister and a fellow chatting while on a woodland walk. As they come upon a little, neglected cottage, the two men reminisce about the old widow lady who used to live there, who had lost her husband in the Civil War, maybe at Fredericksburg, or maybe Gettysburg. The conversation is about two creeds, one religious, the other political, and how, for some Americans these creeds are no longer sacred, no longer true. If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to retell some of this story:

Whatever else the Civil War was for

It wasn’t just to keep the States together,

Nor just to free the slaves, though it did both.

She wouldn’t have believed those ends enough

To have given outright for them all she gave.

Her giving somehow touched the principle

That all men are created free and equal.

And to hear her quaint phrases—so removed

From the world’s view to-day of all those things.

That’s a hard mystery of Jefferson’s.

What did he mean? Of course the easy way

Is to decide it simply isn’t true.

It may not be. I heard a fellow say so.

But never mind, the Welshman got it planted

Where it will trouble us a thousand years.

Each age will have to reconsider it.

The poem continues, with the minister recounting the perspective of the liberal youth, who said some of the words of the creed weren’t true and should be changed, and so the minister thought maybe he would exchange an old phrase for a new one; that he would change the Creed a little. But then “the bare thought”—

Of her old tremulous bonnet in the pew,

And of her half asleep was too much for me.

And so the minister wrestled with his conscience. If the words weren’t true, then

Why keep right on

Saying them like the heathen? We could drop them.

Only—there was the bonnet in the pew.

Such a phrase couldn’t have meant much to her.

But suppose she had missed it from the Creed

As a child misses the unsaid Good-night,

And falls asleep with heartache—how should I feel?

I’m just as glad she made me keep hands off,

For, dear me, why abandon a belief

Merely because it ceases to be true.

Cling to it long enough, and not a doubt

It will turn true again, for so it goes.

Most of the change we think we see in life

Is due to truths being in and out of favour.

Today the truths of the old American Declaration are out of favor again. There are many who want to change the creed, drop the old phrases and ideas and adopt new ones. Even if some of us will miss these from the creed, “as a child misses the unsaid Good-night, and falls asleep with heartache.”

Those quaint old phrases of the Declaration of Independence, like the idea that all men are created equal. That’s a hard mystery of Jefferson’s, as Frost acknowledged. What did he mean by it? Is it true? Of course the easy way is just to decide it isn’t true.

Like Robert Frost, Harry Jaffa liked to talk about that mystery. He spent his whole life teaching about that mystery. At the heart of Crisis of the House Divided (1959) we see Lincoln wrestling with that riddle and answering it in a way worthy of Jefferson’s truth, and of Aristotle’s too. Like Frost, Jaffa taught us that we have to have something to say to the Sphinx. And I suppose we have to have something to say to the Swede as well, and to all who claim that the American way is a conspiracy against the common man.

For Frost, “[T]he answer” to this was “that that’s what it was intended to be.” The American creed “was intended to be a conspiracy against the common man. Let him make himself uncommon.”

Thank you. And Good Night.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The country is now filled with people who chant for its death.

How did this coordinated mass murder become so irrelevant?

Conservatives and non-woke liberals must draw a line in the sand against racialized indoctrination.

All hands on deck as we enter the counter-revolutionary moment.

Elite universities have failed to produce elites.