Restoring pride in the military will require a massive effort.

Sheeple in Leaders’ Clothing

Modern “leadership” is a poor substitution for true statesmanship.

This essay is an adaptation of a talk that was given at Hillsdale College on March 25, 2023 for the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the founding of the Van Andel Graduate School of Statesmanship.

When I taught a class called “Introduction to Leadership,” I would begin by asking my students, “who was the better leader: Winston Churchill or Adolf Hitler?” The question brought to the surface a confusion between two classical categories—tyrannical and just rule. Today we are encouraged to think of leadership as a social science, which obfuscates the classical distinction. Furthermore, leadership understood this way is worth big bucks: “leadership development” is a $366 billion global industry. We have never been so obsessed with the concept of leadership, and yet we have never been so confused about what it actually is.

James Madison writes in Federalist 57, “The aim of every political Constitution is or ought to be first to obtain for rulers, men who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue the common good of the society; and in the next place, to take the most effectual precautions for keeping them virtuous.” The order here is instructive: you need statesmen before you need constitutional restraints on statesmen. Written constitutions with separations of power and checks and balances are wonderful inventions, but they will not save us. The character of any regime is provided by its statesmen, its leadership class, since they embody and maintain the prevailing standard of excellence toward which the rest of the regime is oriented. The nature of statesmanship can be partially revealed by its negative image in the bland, apparently apolitical modern substitute: leadership.

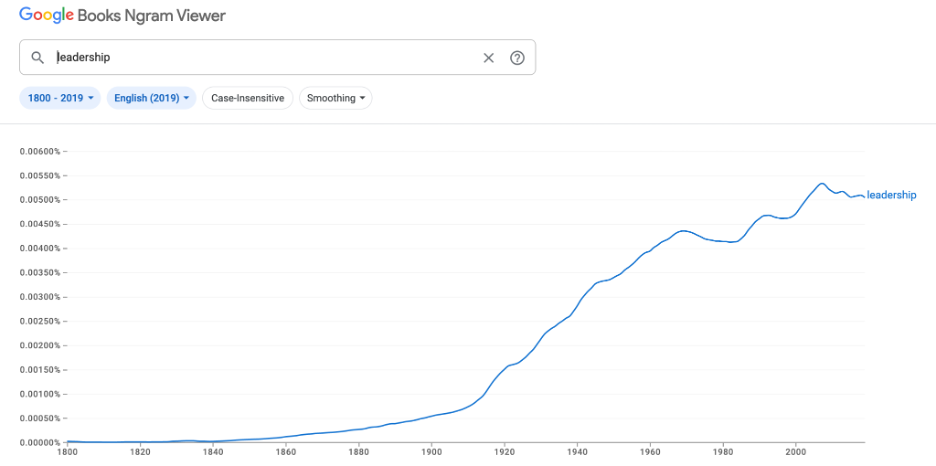

Before the twentieth century, the word leadership almost never appeared in print. Before the 1990s, very few leadership development programs existed. Today they are everywhere, in large public universities, small Christian colleges, and throughout the private sector among the consulting class. How many of us have been subjected to mandatory “leadership training” sessions composed of empty platitudes and personality assessments, designed to pad the pockets of the purveyors and stroke the egos and inflate the CVs of the participants? What accounts for this unprecedented increase in interest in leadership training, and what does this phenomenon reveal about the difference between leadership and statesmanship?

The Great and the Good

Winston Churchill lamented in his day that great men in America tended to go into business rather than politics. It seems we Americans are particularly tempted to confuse the expression of our political nature with the skill for acquiring wealth. In this light, Benjamin Franklin’s spin on Aristotle’s estimation of man as not a political but a “tool-making animal” makes a certain degree of sense. But of course, though the Americans of Franklin’s and Churchill’s days may have begun to prefer business to politics, they were not confusing the two as we have.

Today, this confusion surrounding leadership illustrates its inadequacy as a concept to replace that of statesmanship. In particular, “leadership” is subject to at least three telling contradictions.

The first of these is the attempt to reconcile inequality with equality, superiority with mediocrity. Consider the term democratic leadership: on its face, it is as oxymoronic as jumbo shrimp. In the ancient Athenian democracy, all public offices except that of general were filled by lot. This method for identifying leadership adheres strictly to the principle of equality without regard to any degree of merit. Likewise, people today are not comfortable with the idea of excellence or superiority that naturally attaches to the concept of authority. We want everyone to be a leader or at least a potential leader. In this way, democratic man’s faith in equality spills over into hubristic confidence that the majority of people can somehow be above average.

Alexis de Tocqueville describes this tension indirectly in Democracy in America. Comparing democratic with aristocratic nations, he writes that “Equality is perhaps less elevated; but it is more just, and its justice makes for its greatness and its beauty.” But then in a chapter describing the utility of classical literature for educating the leadership class in a democracy—the de facto aristocracy—he notes that “there is no literature that puts the qualities naturally lacking in the writers of democracies more in relief than that of the ancients,” noting that in them “the search for ideal beauty constantly shows itself.” Though democracy can indeed be a beautiful thing, it needs to be guided by men who themselves are oriented to “ideal beauty,” a standard that judges all things—including democracy—as ugly when they fail to approximate that standard.

An education in statesmanship teaches one how to reconcile these things properly. For example, when I taught leadership classes, I had freshmen read the Seventh Debate between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas. Lincoln there asserts that the moral argument of the Declaration of Independence is based not on a historically-contingent opinion, but on an assumption of “the eternal struggle between…right and wrong…that have stood face to face from the beginning of time, and will ever continue to struggle.” It is this standard that justifies democracy by judging all men equal on the basis that no man is a rightful tyrant. Obfuscating this standard and directing people’s attention away from what Lincoln calls “the real issue” at the time—i.e., slavery—earns Douglas Lincoln’s condemnation for practicing “false statesmanship,” or—to ignore the fact-value distinction assumed in all social science—“false leadership.”

I also had students read Winston Churchill’s novel Savrola. At one point in the story, Churchill has the titular protagonist insist in private conversation that “all things are perpetually referred to an eternal standard of fitness, and that right triumphs over wrong, truth over falsehood, beauty over ugliness.” Churchill scholar Larry Arnn argues that Savrola appeals to this same standard when he asserts in a public speech the equal right “‘even of the most miserable of human beings’ to happiness.” But while this standard establishes an equality on one level, Savrola claims in private that it also establishes “standards of excellence…standards so high that whole generations do not produce a single soul to meet them” and which impose limitations “even upon democracy.” In other words, the same moral authority that condemns tyranny in the name of equality vindicates excellence in the name of inequality.

The Tribe of the Eagle

A second contradiction in the modern view of leadership attempts to reconcile the desire of an individual to hold a leadership role with the egalitarian ends of democratic service. Accordingly we find official theories of leadership with such names as “compassionate leadership” or “servant leadership” or even—I kid you not—“followership” put forward as genuine theories of leadership.

I stumbled across a leadership post online recently that represents well this democratic resentment toward the ambition inherent in leadership. The post had a picture of a rather effeminate-looking man holding a finger over his lips with the caption, “If you are talking more than listening as a leader, you are doing it wrong.” Imagine thinking that the preeminent skill of leadership was not what people thought it was for thousands of years, i.e., the active capacity of rhetoric or oratory, but in fact something quite its opposite, the passive activity of listening. One might more aptly style this “longhouse leadership.”

While moderns struggle not to blush at the thought of desiring to rule for any other reason than to serve others, the ancients considered ambition itself a virtue. Aristotle writes that “we blame the unambitious person, on the grounds that he chooses not to be honored, even with regard to beautiful things” (Nicomachean Ethics IV.5). Likewise when the revolutionary protagonist of Savrola considers what has motivated his thankless struggle, he must conclude that not altruism, not “a people’s good,” but “ambition was the motive force, and he was powerless to resist it.”

The ancient view of leadership or statesmanship accepted the legitimacy of ambition as a motive for ruling by acknowledging that the beauty of daring deeds, done for right reasons and in the right way, does not depend on the approval of a multitude. Command for the sake of the common good does not require a servile motive to be legitimate.

Never Neutral

A third and final contradiction assumes that leadership can be apolitical—and thus amoral—but also not tyrannical, which is to say very moral indeed. Leadership as a social science lacks any category by which to recognize and distinguish evil from good leadership, because while it lays claim to ultimate authority, it also rejects ultimate responsibility for choices within a moral framework. For all the ethical language one hears in leadership development circles, “good” and “bad” leadership there has less to do with the moral quality of the path a leader chooses and more to do with how said leader persuades people to follow him, whether he uses forceful (bad) or gentle (good) means of persuasion (e.g., whether he uses inclusive language). Consequently, the horizon of leadership is reduced by the same degree that it refuses to address but instead presumes answers to political questions.

What is the alternative view? In the beginning of the Nicomachean Ethics (1094a1-b12), Aristotle provides an account of the hierarchy of sciences that corresponds to the hierarchy of ends that must exist because we all do some things for the sake of other things. The “most authoritative and most architectonic” science, he writes, “appears to be the political art.” This would be the true science of leadership, of authority. Aristotle claims that all others, “even the most honored capacities…fall under the political art,” and he names three specifically: generalship, household or wealth management, and rhetoric. It turns out that these three vie with each other to dislodge the political art from its place of authority over the rest.

All three of these sciences command respect. Aristotle describes them as “the most honored capacities.” From what I have seen, most leadership studies and leadership training programs that were founded over the last three decades were founded by people who did not themselves earn degrees in “leadership.” Rather, they came from military, businesses, or communications and psychology backgrounds. This fact is illustrative if we consider Aristotle’s observation that these sciences fall under and thus are not themselves the same thing as the science of leadership. What becomes of these sciences when they become untethered from the moral authority of the political art and presume to understand the art of leadership itself?

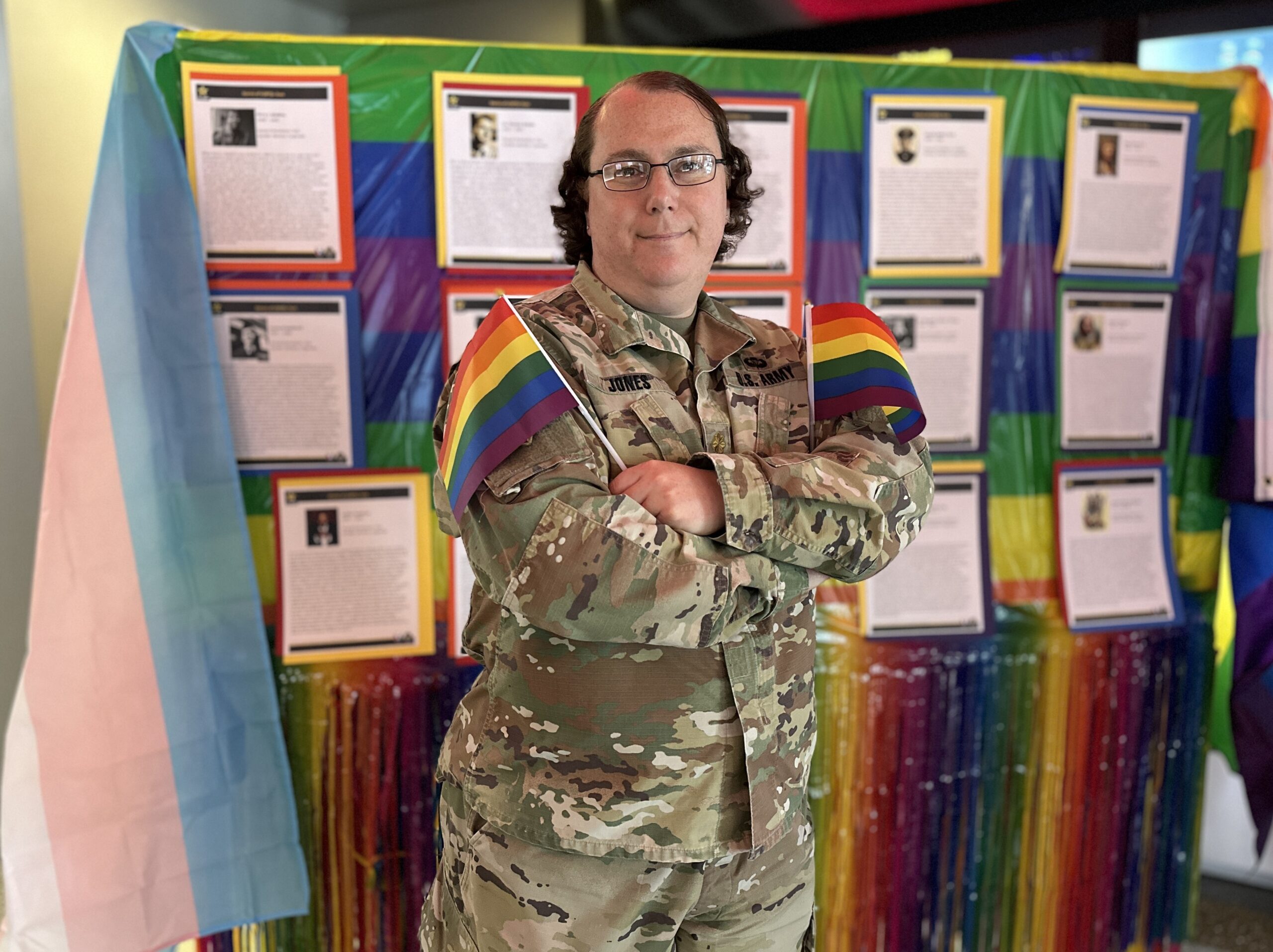

Generalship: As our military leaders today reveal in alarming ways, the art of generalship needs direction to know who is and who is not the enemy and what is the object of victory. Unlike the Guardians in Plato’s Republic (375d), we cannot expect our soldiers to be “philosophic guard dogs,” who know instinctively who is a friend and who is an enemy. Aristotle’s criticisms of Sparta (Politics 1269b14-40 and 1271b1-11) are instructive: if you make military generals your political leaders, they will reduce your city to a military camp. The men will become ruthless, and the women dissipated.

Insofar as the military art aims at preserving mere life, it is similar to the medical art. In the year of our Fauci 2020, we all witnessed what happens when the medical art assumes the leadership role and directs political affairs: concern for the preservation of mere life eclipses all reasonable concern for the pursuit of living well. Despite the accolades we are accustomed to bestowing on military officers, leadership properly understood cannot be equated with the military art.

Household Management: Household management, oikonomia or oikonomikē, has more going for it than the military art, according to Aristotle; it at least involves the virtue of prudence, as the political art does. Aristotles describes prudence as the ability “to observe the good things for oneself and those for human beings.” And he adds, “We hold that skilled household managers and politicians are of this sort” (NE 1140b). This overlap with the political art may explain why most leadership books have been written by and for people in business.

Critically here, Aristotle reveals the sometimes fine but fundamental distinction between leadership and what we call management. With the rise of the administrative state, the complications that follow from trying to separate the science of management or “administration” from that of “politics,” as Woodrow Wilson put it, have become manifest. We know that this distinction collapses at some point: personnel is, in fact, policy. Administration is political. Nevertheless, there is at least something to this distinction.

I will credit one modern leadership book for helping to make this distinction clear. Stephen Covey’s highly praised The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People includes a chapter on what he calls “personal leadership” that involves the habit “Begin with the End in Mind.” This chapter is basically a handbook for learning to think teleologically. Charles Haywood—a man who seems to understand well the art of wealth management—directed me to this chapter in an interview he gave at IM—1776.

To distinguish management from leadership, Covey makes an analogy. Imagine, he suggests, a group of people trying to cut through a jungle. The workers are up front cutting through the brush, and the managers are in the back, helping sharpen machetes, writing safety policies, scheduling breaks for workers, etc. The leader, Covey says, is the guy who climbs up above the tree line, gets the lay of the land, and yells down to the managers: “Wrong jungle!” Management is about accomplishing a given task, while leadership is about choosing the right tasks that accord with a moral view of the Good.

The Constitution, Covey writes, is like management; it is the process for cutting our way through the jungle of events as a people. The Declaration of Independence, he says, provides the moral vision for leadership to guide that process. As Lincoln argued in the Seventh Debate with Stephen Douglas, when someone would have us view the Constitution as a document that supports slavery, the Declaration alone is able to say: “Wrong jungle.” Despite Covey’s best efforts to distinguish the business art of management from the moral philosophy of leadership, though, businessmen often still conflate these two, presuming that a masters degree in business administration is some kind of credential of expertise for leadership.

The arts of business and management ultimately fall under the science of leadership because these arts can only cognize the human good in some partial way by providing some particular good or service. The science of leadership, though, must have an understanding of human flourishing as a whole to understand how a particular good or service might serve that larger aim. Prudence, Aristotle notes, is the ability to deliberate nobly about the human good, not in a partial way—such as things “conducive to health and strength”—but about “the sorts of things conducive to living well in general” (NE 11140a).

Rhetoric: Finally we come to the art of rhetoric and its presumptions to leadership. In the last chapter of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle notes that the Sophists

who profess to teach the political art appear to be very far indeed from doing so. For in general they do not even know what sort of a thing it is or with what sorts of things it is concerned: otherwise they would not have posited it as being the same thing as rhetoric—or even inferior to it.

Deliberating upon what the laws should be, the Sophists believe, is an easy task; it is persuasion that is the difficult thing. In Aristotle’s Rhetoric (1356a), he notes that the rhetorician, in order to use ethos for persuasion, must be able “to understand human character and goodness in their various forms.” Because rhetoric thus requires an understanding of various human characters, Aristotle suggests that “it thus appears that rhetoric is an offshoot…of ethical studies,” which he asserts “may fairly be called political.” And then he makes a most remarkable claim: “and for this reason rhetoric masquerades as political science, and the professors of it as political experts” (emphasis added). Thus we find that those who study communications and psychology—the means of persuasion and manipulation of the human soul—have great insight into rhetoric, but they often assume this insight provides them with expertise in leadership also.

The limitation and power of rhetoric, Aristotle warns, is that it is not “the scientific study of any one separate subject” but is instead a faculty for providing arguments for any subject. The science of employing arguments against an opponent is insufficient for leadership, though, for the same reason that the military art is for deploying soldiers against an enemy: its science cannot tell us who the enemy is or what the point of victory is. Likewise, rhetoric, the art of persuasion, is similar to the art of money-making with regard to marketing insofar as it is the art of making a single product or service—a partial view of human flourishing—seem sufficient for living well in general.

The Sophists, ancient and modern, are wrong: rhetoric is not the whole of leadership. It is, though, an art that the statesman finds indispensable. It is necessary, but not sufficient. Conflating rhetoric with leadership and thinking of leadership thus as a distinct science with its own subject matter is tantamount to claiming to have expertise in expertise.

The Human Roadmap

The unique quality of true leadership, in the form of statesmanship, is in fact nothing short of human excellence. On one hand, it is simply the art of rhetoric paired with the virtue of prudence—deliberation and decision. But on the other hand, as Aristotle notes, one cannot be prudent if one lacks courage, ambition, liberality, or justice.

This kind of person is a rare sight. We have various words to describe him: we say such a one has integrity, wholeness. This is a complete human person, or simply a good person. Aristotle calls this person a spoudaios, which is sometimes translated as a “morally serious person.” The unique ability of the spoudaios is to see what is good “in a true sense,” while everyone else sees only what they wish as an “apparent good.” The spoudaios, Aristotle says, “is distinguished perhaps most of all by his seeing what is true in each case, just as if he were a rule and measure of them” (NE 1113a20-33). This is the true essence of leadership, when the excellence of a person becomes the very rule and measure of the good for others to see because he himself is good. Put another way, consider that the polyseme ruler means both “he who commands” as well as “the standard by which other things are measured.” Hence—taking into account the proper role of rhetoric—true leadership appears to me to be this: compelling human excellence.

For moderns, leadership is a kind of skill set that anyone can learn through study, and accordingly those who learn the arts of generalship, wealth management, and rhetoric assume that their teachable science is the whole of leadership. The classical view of leadership, however, is not about learning a skill set by which to manipulate others. It is more like becoming a roadmap that others read to understand what human excellence is and by which they are themselves measured. Such a condition gives one the ability to see and then illuminate in any given dilemma what the truly good and beautiful choice is.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

War: What is it good for?

The U.S. military has deteriorated to the point where it might not be able to win even one major battle, much less two simultaneously.

Our nation’s priority should be fixing its men.

President Biden’s reading of the Second Amendment is seriously off-kilter.

The new U.S. military seems designed to lose wars and destroy morale.