How to understand—and rectify—the foreign policy disaster of 2024.

Hollowed Out

The U.S. military has deteriorated to the point where it might not be able to win even one major battle, much less two simultaneously.

Most military experts agree that the U.S. military is no longer capable of achieving its mission as mandated by national defense doctrines adopted by administrations of both parties. President Biden is exacerbating the situation by focusing military strategy on progressive politics instead of military preparedness. Even a Democratic controlled Congress overruled his proposed budget in order to increase spending and partially to fund programs required to reverse the decline.

While the U.S. military remains the world’s most powerful military, it also has the broadest mission of any nation, with global security needs and commitments. Those proud of U.S. capabilities fairly observe that no other nation could have evacuated 124,000 people in two weeks from Kabul. Nonetheless, insufficient funding, slow modernization, and woke mandates are hollowing out the military’s readiness and capacity to achieve its mission.

The Heritage Foundation has observed that the U.S. Army is the smallest it has been since 1940, the Air Force is the smallest and oldest it has been since its inception, and the Navy is far from its goal of 350 ships and retires more ships than it builds. New technologies enable only a portion of the contraction.

Each year since 2015, the Heritage Foundation has published an extensive assessment of global military risks and the readiness of the U.S. military to address those risks and perform its mission. This year, the Index of U.S. Military Strength concluded that the global operating environment is “favorable,” meaning that America’s global presence and alliances are supportive of U.S. military needs, but the threats to U.S. interests are growing, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s aggressive behavior in the Pacific, and provocations from Iran and North Korea. The Index ranks the overall global threat level as “high,” the second highest of its five threat categories.

As it assesses the U.S.’s ability to repel these threats, the Index reports, “as currently postured, the U.S. military is at growing risk of not being able to meet the demands of defending America’s vital national interests. . . . This is the logical consequence of years of sustained use, underfunding, poorly defined priorities, wildly shifting security policies, exceedingly poor discipline in program execution, and a profound lack of seriousness across the national security establishment.”

Based on its mission—the ability to prevail in two approximately concurrent major conflicts, while also preserving freedom of movement in the sea, air, outer space, and cyber domains—the Index ranks overall U.S. military power as “weak.” As touched on below, the Index’s methodology somewhat understates U.S. strength, but the reprieve would be short-lived given current trends.

Because of rising costs, progress made under the Trump Administration was lost in 2022. The Index’s forecast for 2023 is “gloomy,” given a proposed defense budget for FY 2023 that does not keep pace with inflation. Downsizing the number of experienced troops and officers, while failing to meet enlistment goals, is reducing the quality and number of recruits.

With minor exceptions, the Index disregards the Ready Reserve and National Guard. Given the integration of these elements with active duty military, this may overstate some concerns regarding the Army and Air Force. Conversely, the weak condition of the U.S. military is more pervasive than a shortfall in the number of combat units and ships. There is a shortage of advanced weaponry; munitions; state-of-the-art technology; flight time for pilots; and other training. The average age of most equipment is nearing, or exceeding, its recommended lifespan. Nuclear forces are likely capable of being reliably used for strategic purposes but soon will confront substantial failures as missile parts and detonators deteriorate past the point of viability. There is no reasonable basis for believing the U.S. military could concurrently prevail in two major conflicts, and there is a reasonable basis to fear it might not prevail in even one.

Though the U.S. Army remains the world’s most powerful army, that advantage is eroding. Given America’s global commitments, being the “most powerful” is more of a talking point than an effective advantage. The Index ranks the Army as “marginal” but credits it with undertaking a modernization program that, if fully funded, could improve that score. At present, the Army is aging faster than it is modernizing. It fields only 62 percent of the force it should have, though more than 80 percent of brigade combat teams (BCTs) are at the highest state of readiness, slightly ameliorating the shortfall.

Taking inflation into account, the Army has lost $46 billion in buying power since FY 2019. Based on the administration’s last request, it will lose close to a further $10 billion during FY 2023. U.S. Army Chief of Staff General James McConville believes the Army needs at least 55,000 additional troops, an 11 percent increase. The Army’s last major modernization program occurred in the 1980s. Today, both Russia and China deploy artillery and missiles with range and other capabilities not available to the U.S. Army.

In February 2022, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Mike Gilday testified that the U.S. Navy needs more than 500 ships, including aircraft carriers, amphibious landing craft, destroyers, frigates, attack submarines, ballistic missile submarines, support ships, and “looking into the future” about 150 unmanned ships. Presently, the Navy has 298 battle ships, generally achieving Gilday’s goals only for carriers and ballistic submarines. The country lacks the shipbuilding capacity and workforce, sailors, budget, and commitment to meet Admiral Gilday’s goals, or even the more conservative goal of 400 ships suggested by the Index. Instead, absent a considerable increase in sustained funding and improvements in shipbuilding infrastructure, the fleet is expected to decline to 280 ships by 2037. Concomitantly, the Navy estimates it needs an additional 35,000 sailors. Instead, it is losing sailors.

The Index and Admiral Gilday might overstate the number of required ships by using the historical ratio of about six ships being used for rotation to and from port, training and maintenance, for each ship forward-deployed. Because of necessity, the Navy is currently operating with a ratio of approximately 2:1. Though that ratio is unsustainable, the sweet spot might be somewhere in the middle, implying that a 350 to 400 ship navy might be adequate.

The Index ranks the Navy as “weak,” driven by an insufficient number of ships and inadequate training.

The Marine Corps is the bright spot in the Index’s assessment, scoring “strong” because its more limited mission contemplates only one major battle at a time and because of the sustained vigor of its modernization program. Still, the Marine Corps is suffering from diminished resources, with its force trending down from 202,100 in 2011 to a target of 177,000 for FY 2022. Correspondingly, the number of battalions is falling, with the loss of another battalion scheduled this year. The Corps has only 66 percent of the pilots it needs for its fixed-wing aircraft, despite a 70 percent reduction to 18 squadrons from the 28 squadrons it had during Desert Storm. The Corps also is shedding capabilities such as tanks and artillery that it might require in a major action.

In 2017, then-Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson and then-Air Force Chief of Staff General David Goldfein testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee that the Air Force is “at our lowest state of readiness in our history.” Thereafter, then Secretary of Defense James Mattis directed the Air Force and Navy to increase the mission-capable rates of its fighters to 80 percent. The services failed to do so, and in 2020, Goldfein said meeting that goal was no longer a priority. According to the Index, the Pentagon has “stifled open conversation or testimony about readiness” making assessments difficult. Nonetheless, the evidence is that the number of combat-ready fighters has declined, fewer pilots are joining the Air Force, and flying hours have declined to historic lows. Despite reductions that Wilson acknowledged left the Air Force 25 percent smaller than it requires for combat with a peer competitor, the service intends to further reduce its fighter force by 19 percent.

Today, taking into account reserve squadrons, the U.S. could deploy 885 combat-coded fighters, barely enough to oppose a peer competitor. Their average age is 29.4 years. The average age of B-52 bombers is more than 60 years and KC-135s, which comprise 75 percent of the Air Force’s tankers, average more than 61 years old. The Air Force is short 650 pilots, and pilots are flying barely more than once per week, less than half the flight time required by the Air Force to qualify pilots to fly combat missions. It has been several years since the U.S. acquired missiles capable of countering GPS/electronic jammers. Available munitions probably would last only a few weeks, and unlike World War II, there is at least a 24 month to 36 month lag between funding and delivery of additional munitions.

The Index ranks the Air Force as “very weak,” because “mission readiness and physical location of combat aircraft imply that it would have a difficult time responding rapidly to a crisis.”

Both China and Russia are capable of disabling American satellites. Space Force, created on December 20, 2019 to protect the U.S. and its allies, has developed only limited defenses and, based on publicly available information, has only one basic offensive system to interfere with an adversary’s satellites. The Index ranks Space Force as “weak.”

Nuclear weapons are the backbone of U.S. power. The belief that the U.S. would use strategic nuclear weapons deters aggression against the U.S. and more than 30 allies to whom the U.S. has made commitments, while reassuring and disincentivizing them from developing their own nuclear weapons. The U.S. nuclear arsenal was configured based on the Soviet threat. Today, the U.S. confronts two nuclear peers, Russia and China, as well as threats from North Korea, Iran, and terrorists. Russia and China are aggressively modernizing and expanding their nuclear capabilities, including nuclear-powered cruise missiles, nuclear-capable unmanned underwater vehicles, and hypersonic glide vehicles. Russia alone maintains at least 2,000 tactical nuclear weapons, compared to fewer than 200 in the U.S. arsenal, while China is engaged in what Charles Richard, Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, describes as a “breathtaking” expansion of its nuclear capabilities, including an orbital bombardment system.

By contrast, with modest exceptions, U.S. capabilities and its arsenal date from the ’70s and ’80s, with many warheads and delivery systems at, or beyond, their intended lifetimes. To meet the challenge of preserving a credible nuclear deterrent, the U.S. must refurbish, modernize, and expand its nuclear capabilities, including a range of tactical weapons, and must recruit and train a new generation of personnel to replace the rapidly retiring generation of nuclear engineers.

The Index ranks U.S. nuclear capabilities as “strong” but rapidly deteriorating toward “marginal” or even “weak” as the threat environment grows. The U.S. falls behind in tactical and hypersonic weaponry and confronts improved defensive capabilities that it may not be able to overcome. For example, nuclear gravity bombs have been removed from the bomber fleet based on the assumption that U.S. bombers will not be able to reach their targets.

U.S. missile defense consists of systems to protect the homeland from intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and tactical systems to protect ships, land bases, and civilians. The U.S. maintains 44 ground-based interceptors capable of shooting down long-range ballistic missiles headed for the homeland. Because multiple interceptors are launched against each incoming missile, this system likely would only protect the U.S. against a small number of incoming missiles. The Aegis defense system, usually deployed aboard ships, is effective against missiles with ranges from about 500 miles to 3,000 miles.

In addition to systems intended to intercept missiles in flight, the U.S. deploys systems intended to intercept missiles as they are descending to strike. The Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAD) is transportable and can shoot down short and intermediate range missiles inside and just outside of the atmosphere. The Patriot system also is transportable and targets missiles during their final descent.

The U.S. has no system capable of destroying a missile while in its launch phase and only one limited system capable of engaging hypersonic missiles. With the proliferation of sophisticated missile systems by multiple adversaries and the mission critical requirement to protect ships, bases, and population centers, U.S. missile defense lacks the capabilities and the number and distribution of interceptors required to achieve that mission. The Index concluded that “the development of missile threats, both qualitative and quantitative, is outpacing the speed of missile defense research, development, and deployment to address those threats.”

U.S. Cyber Command’s mission includes both defense and offensive capabilities. Because most of its capabilities and activities are classified, the Index did not opine on its readiness or success.

The Index’s conclusions are broadly consistent with independent evaluations. For example, in December 2021, Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs released The Great Military Rivalry: China vs the U.S. The report noted that in 1996, China conducted missile tests bracketing Taiwan. The U.S. responded with two aircraft carriers that moved close to Taiwan, and China backed down. If the U.S. attempted the same show of force today, its carriers could be sunk by Chinese DF-21 and DF-26 missiles.

Belfer’s sobering findings are: (1) “the era of U.S. military primacy is over: dead, buried, and gone”; (2) “while America’s position as a global military superpower remains unique . . . both China and Russia are now serious military rivals and even peers in particular domains”; and (3) “if in the near future there is a ‘limited war’ over Taiwan or along China’s periphery, the U.S. would likely lose.”

Belfer observed that China may be ahead of the U.S. in aligning advanced technologies with warfighting concepts, while the U.S. has “doubled down on legacy platforms, and left innovating startups struggling to survive the Pentagon’s acquisitions process.” Recent congressional testimony revealed over the last decade the U.S. has lost every war game in competition with China, excluding only a game that gave the United State the advantages of technology and weaponry it does not possess and, that in some instances, does not exist.

Speaking at an industry conference, Admiral Charles Richard, commander of the U.S. Strategic Command, put it bluntly: “As I assess our level of deterrence against China, the ship is slowly sinking. . . . And that is a very near-term problem.”

Belfer also puts to bed the tired trope about U.S. defense spending exceeding the combined spending of some large number of other countries or even all other countries put together. When adjusting for the differences in items included in reported budgets and purchasing power, China’s budget in 2020 was 53 percent of the U.S. budget, on a “path to parity in the foreseeable future.” The U.S. funds bases and forces to meet global commitments in Europe, the Middle East, South America, and Asia. China is focused on Asia. Much of the U.S. budget is consumed with legacy systems. China’s is not. For the last 20 years, much of U.S. spending has been diverted to wars in the Middle East, while China spent on modernization.

A recent American Enterprise Institute study concluded that more than 14 percent ($109 billion) of the administration’s proposed FY 2023 defense budget is for non-military priorities such as climate change, nondefense health care, and humanitarian aid, underscoring the shibboleth of dominant U.S. military spending.

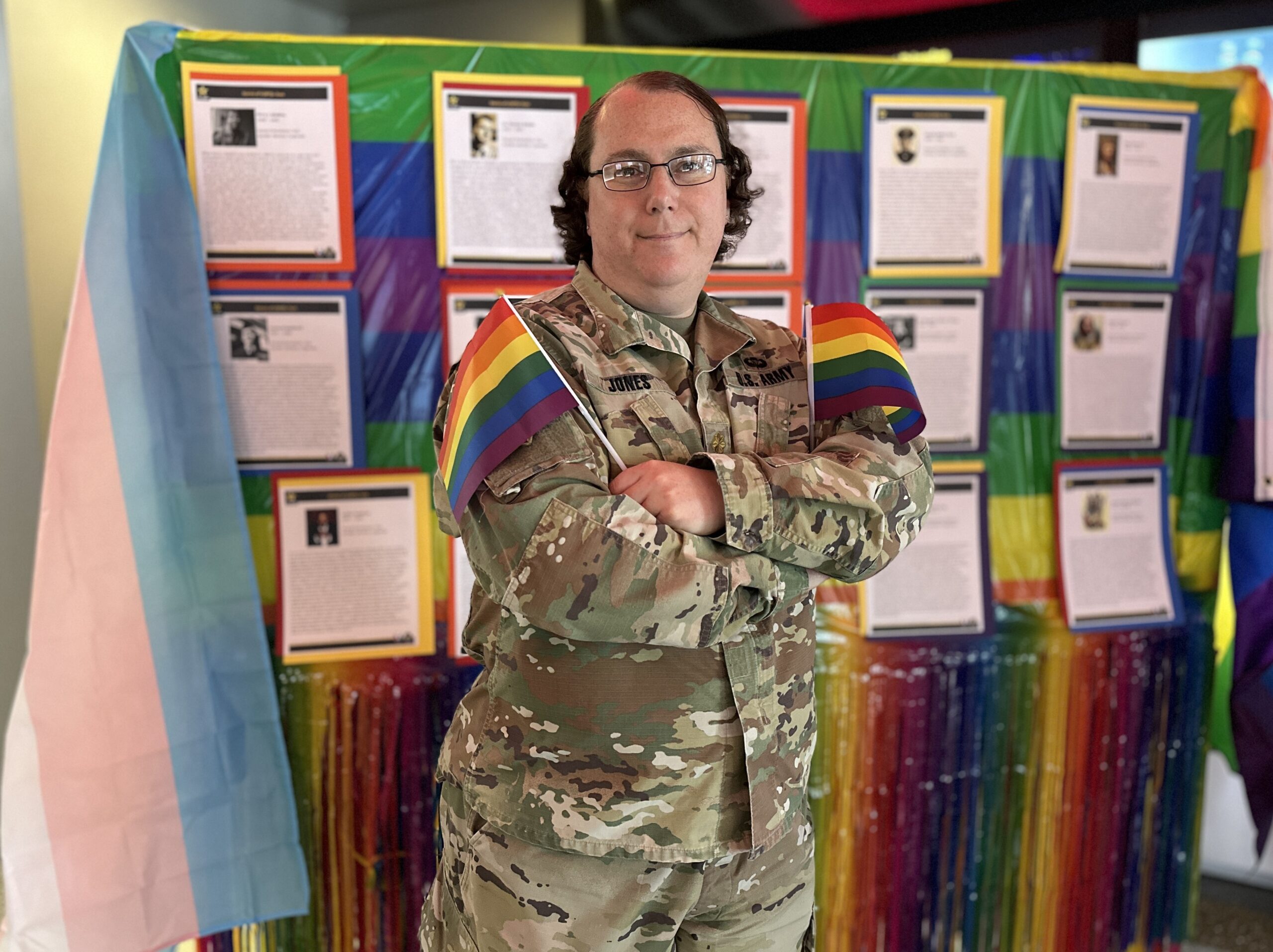

Exacerbating its other problems, each service has failed to meet its recruiting goals. Many see this as partially the result of rapidly increasing wokeness in the military, which is inconsistent with the views of conservative families that historically are the backbone of the force. Writing in inFocus, Heritage Foundation researcher Dakota Woods observed, “More than three-quarters of America’s 17 to 24-year-old youth, who normally constitute the pool of potential recruits, are ineligible because of health problems, obesity, substance abuse, or criminal records. Overall, only 9 percent of American youth express interest in serving. Whatever the overlap between the 9 percent having any interest and the percentage of youth who are eligible, it is likely to be small. In short, few Americans have both the interest and the ability to serve.”

Even with the reduction of spending in the Middle East, budgets are insufficient to modernize and expand the military or support the industrial base and recruitment goals necessary to restore America’s military. One day soon, there may be a major conflict the U.S. will lose. That loss could be much more consequential than U.S. losses in Vietnam or Afghanistan. It will then be too late to fix the problems.

Instead of the administration’s National Security Strategy focusing on diversity, equity and inclusion or climate change as the key drivers of national security, and regardless of whether the U.S. pursues engagements in Ukraine or other hot spots, the administration and Congress must instead focus national security policy on military preparedness and lethality. Peace through strength and the belief that the U.S. will use its strength remains the best prescription for avoiding major military engagements.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The new U.S. military seems designed to lose wars and destroy morale.

President Biden’s reading of the Second Amendment is seriously off-kilter.

Modern “leadership” is a poor substitution for true statesmanship.

Our nation’s priority should be fixing its men.

Democrats are laying the groundwork for revolution right in front of our eyes.