Americans should resist technological subjugation by any means necessary.

Screen Warp

How your phone ate your life.

“Time has passed so funny the past two years…almost like a time warp.”

—Someone you know, 2021-22

In late January 2020, I was preparing for what I thought would become total societal collapse. By March, that initial fear had given way to wariness of never-ending lockdowns. I was 25, living alone in an apartment in a mid-sized city. My tech marketing job could go remote. Though I had dry food, water and firearms, I soon realized the more daunting challenges lockdown would pose to me were boredom and solitude.

The day before lockdowns started, I began worrying I would lose my mind alone in my apartment with my rice, beans, and bullets. I made a last-minute scramble, driving across town in the rain to a strip mall where I’d convinced a GameStop proprietor to stay open an extra 15 minutes and pass a second-hand Xbox One through the cracked door. Sanity secured, I thought.

Little did I know, I would not adopt Xbox as my lockdown pastime. Instead, I started tweeting. I’d lurked on Twitter for some time previously, but in the ensuing lockdown boredom and solitude of March 2020 I found myself writing threads, sharing memes, gaining followers, playing the game.

Then I woke up and it was March of 2022. Prompted in part by reading the 2019 expanded edition of Technological Slavery by Theodore Kaczynski, I took a step back to assess my relationship with technology and, more specifically, my time spent on Twitter. I’d had some fun, plenty of laughs, and met a few friends along the way. Sure, I had thousands more followers than when I started. But what really happened? What did it really mean about those two years of my life?

Distancing myself from the dopamine rush I’d come to unconsciously associate with the bird app, I found that, from March ’20 to March ’22, I gave an estimated 1,000 hours of my otherwise productive time and attention to Twitter, whose executives in turn sold it to advertisers (exactly 1,095 hours if we assume 1.5h avg/day for two years). My input was immense, while the output, kickback, or any sort of measurable benefit to me, was modest at best. I felt short-changed —Twitter had cut me out of the deal! So, I deactivated all of my social media accounts. That was six weeks ago.

Since then, with socials deactivated, I’ve cut my daily screen time by ~30% (from 12 to eight hours a day). I run a cryptocurrency company remotely, something I always felt required a minimum 12 hours a day. As it turns out, it takes less than eight hours a day when I fix the attention leakage of social media.

Every day, around 20-30% of my attention was being stolen by social media. I thought I lived in a world where I “never had time,” my bandwidth constantly stretched. In reality, I was living like a gambling addict who complains about never having money while blowing 20-30% of every paycheck on lottery tickets.

But beyond the quantifiable, during my social media hiatus (the first of my adult life), my subjective experience of time slowed down. The world around me decelerated, I felt more capable than ever of navigating it. Aside from the pace change, a blanket of stress I didn’t know I’d been carrying lifted off me. The sense of having “no time” to clean my apartment, pay my taxes, send packages, write letters, call my grandfather, get my windshield fixed, or play the guitar, vanished.

Was I a debilitating screen addict before? Truthfully, no. I was a high-functioning, highly caffeinated dopamine junkie, riding the tiger of modernity. Twitter was an outlet for me, a place to channel the manic outbursts I suspect evolution intended for physical activity. Despite two years of creeping screen warp, I’d been promoted to COO of my company and received my purple belt in jiu jitsu while working seven days a week, blaming these more formal commitments for my sense of time crunch and burnout. In reality, my life was bleeding out through my fingertips. I thought I was good at playing the Twitter game. But I was being played.

Screen Warp

I cite my personal experiences because they led me to investigate a broader phenomenon that I call Screen Warp. What happened the past few years? Why do we ask one another, “Hasn’t time seemed to pass so fast? You’ve likely had that exact conversation: everyone has.

Screen Warp: A phenomenon in which daily screen-mediated dopamine release causes the subjective experience of time to accelerate.

Most acknowledge that the passage of time has seemed to accelerate as of late, but few consider it beyond a passing remark. What is it that caused this?

Was it the insane pace and intensity of news cycles? COVID became George Floyd became the 2020 Election became the January 6th “Insurrection” became the Afghanistan pullout disaster became briefly COVID again, then inflation, then Ukraine, then hating Elon Musk, then post-Roe outrage (now we’ll have perhaps some gun control and rehashed COVID hysteria to boot).

Reflect for a moment on your life, in particular what your consumption of information and technology looked like two years ago in January 2020. That was over two years ago. Does it feel strange?

What if I told you time has seemed to pass faster because the engineers working on products at multibillion dollar tech companies have, using compounding data insights over the past 5 years, gotten really, really good at their jobs? Your brain was quietly hijacked by irresistible information encoded in blue light, blasted from LCD screens into your unsuspecting eyes, triggering neurotransmitter release in your brain. You’ve been on a slow drip of dopamine. To your brain, it’s indistinguishable from small, frequent administrations of cocaine.

Would it surprise you to learn that screen time is up 30% nationwide for Americans since 2020?

That the dopamine drip of screen time accelerates your subjective experience of time?

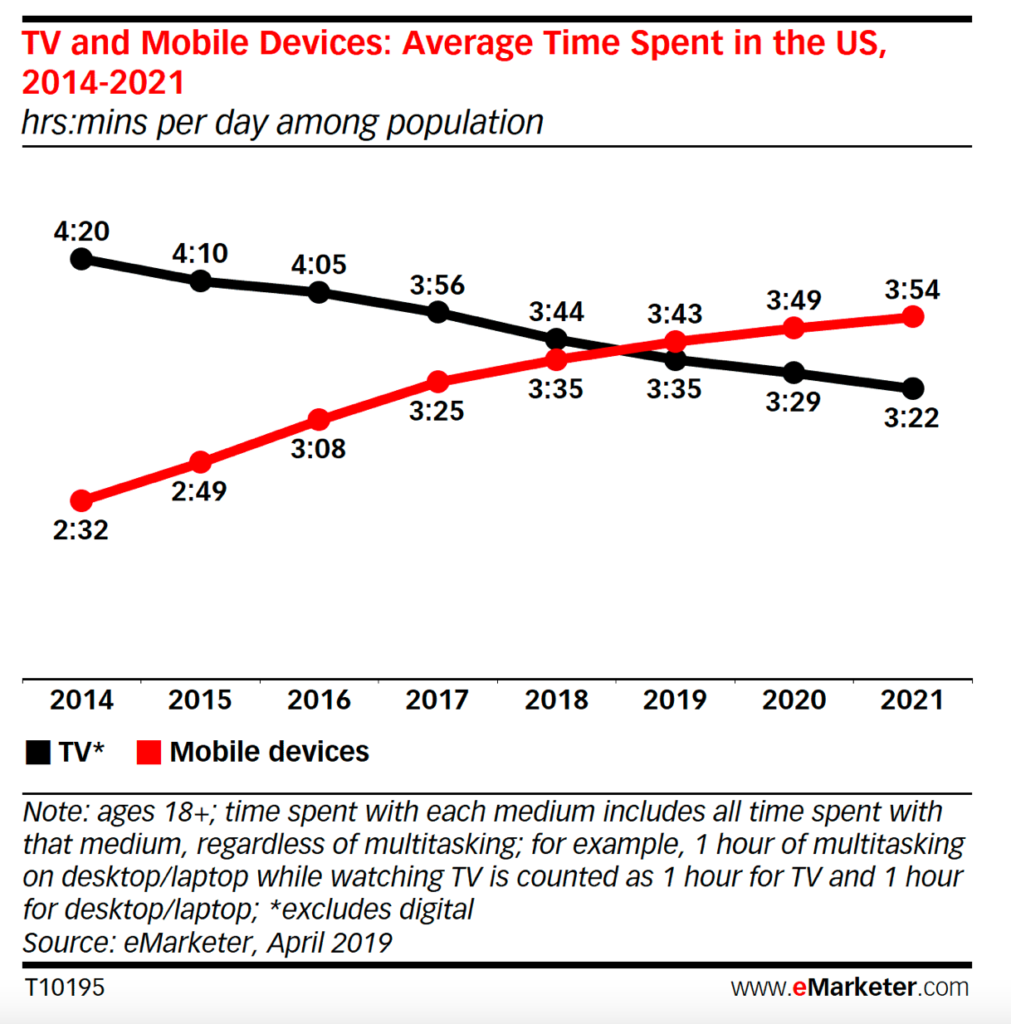

People say they don’t watch TV, as if watching 3+ hours of TV is something only dumb people do. But they’ve just swapped one screen for another. There is significant data on this changing of the guard:

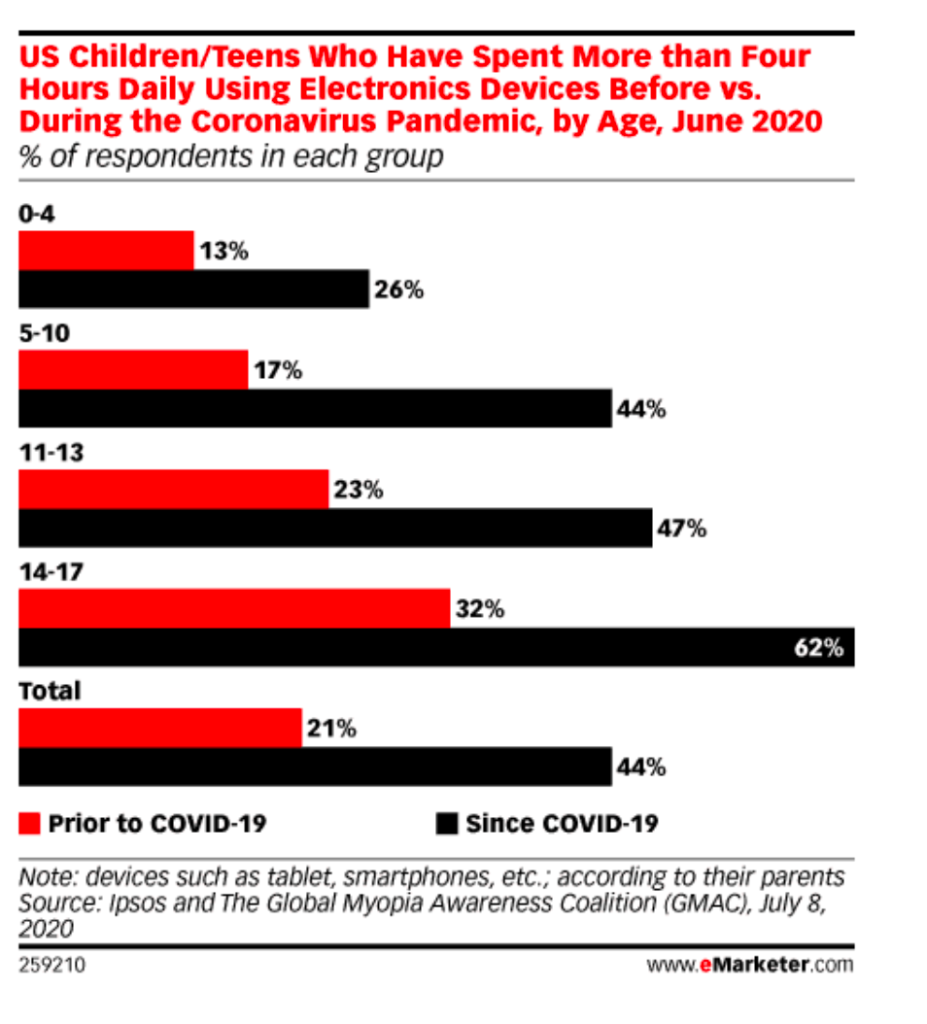

Three hours and 45 minutes a day on a cell phone alone for ages 18 and up. Overall screen time estimates are up 20-30% from 2020-2022. The picture is more bleak for the youth, among whom usage doubled:

Dopamine and Time

What follows is a broad oversimplification of the research backing the aphorism that “time flies when you’re having fun.” More specifically, triggering dopamine activity speeds up both humans’ and animals’ internal clocks, leading them to underestimate time intervals. According to Emily Singer of the Simons Foundation:

Dopamine is a brain chemical best known for its role in reward, motivation and movement. But scientists have long suspected that dopamine also plays a role in the perception of time. People with disorders linked to dopamine defects, such as Parkinson’s disease, have problems tracking time. And animals dosed with drugs that trigger the release of dopamine respond to tasks more quickly than usual, suggesting that the animal’s internal sense of time is sped up.

As discussed at length in Dopamine Nation by Stanford psychiatrist Dr. Anna Lembke, dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter used to track relative addictiveness of substances or activities. By the dopamine measure, the addictiveness and pleasure of cocaine is the same as that of heroin, is the same as that of methamphetamine, is the same as that of pornography, is the same as that of gambling with screen time.

Screen time triggers dopamine release, and behaviors triggering dopamine release create habit patterns. This is the vicious cycle that billions of dollars of research have been spent to achieve across a variety of industries. The addictive foods you eat, drugs you use, and behaviors you engage in all rely on the same mechanism.

Less frequently discussed is the fact that dopamine causes time contraction, the acceleration of perceived time (the opposite of time dilation). Time contraction is an incidental byproduct of dopamine release in your brain’s frontal cortex. What else does this? Most common addictive substances and activities (cocaine, methamphetamine, porn, gambling). According to Lembke, in her field of addiction counseling, the new entrant on the scene is screen addiction.

We don’t yet see it like cocaine or meth, because it seems so harmless: you can be a high-functioning screen addict, like I was. But screen use reduces impulse control and accelerates perception of time just like any drug: “Studies have found that increasing dopamine speeds up an animal’s internal clock, leading it to overestimate the passage of time; others have found that dopamine compresses events and makes them seem more fleeting; still others have uncovered both.”

Bits and Atoms

For years we’ve taken it for granted that the world of bits would subsume meatspace (or, to paraphrase Peter Thiel, that bits would eat atoms). In the decade leading up to 2020 our education, entertainment, commerce, socialization, romance, work, and play had all become increasingly screen-mediated at a pace slow enough to not raise alarm, but fast enough to entirely transform what it is to be human in less than a generation.

COVID proved an unlikely high-octane accelerant for this process more effective than anything tech companies could produce in their labs. Prior to COVID, many of us were digitizing our lives piecemeal, each year engaging more with our screens than the physical world, and increasingly sourcing our basic human needs—food, water, shelter, community—as well as higher-order needs—vocation, avocation, entertainment, currency—through our device screens. Until March 2020, digitization was a slow creep.

Then, COVID removed the optionality and gradualism from the processes. Your screen wasn’t a way to get your needs met: it was the only way. Screens provided the all-in-one solution to COVID lockdowns. From your groceries, to your conversations with friends and family, to your evening entertainment and dating prospects, the black mirror provided all. No one blinked.

Beyond immediate human needs, our screens also became more than ever a means to engage with ideas, politics, and general social belonging. While this was not a bad temporary solution to the reality of physical isolation from other human beings, COVID prompted a massive leap forward, never to be rolled back. The temporary fix became permanent. We live not just as much, but more in the world of bits now than ever before 2020.

If you were on the Right but not already a member of the “online Right,” COVID converted you. Someone already “online Right” became “very online Right,” and so on. The same goes for the Left. While it remains to be seen how far left or right COVID pushed the average person, there is no debate that it pushed him or her closer to the screen.

Screen Society And The Future

Now, two years later, a return to normalcy is unlikely, if possible at all. Will you ever return to your screen time averages of January 2020? Not without intentional effort. Technology is two years better at holding your gaze, and circumstances have conspired to block you out of activity, interaction, and opportunity in the real world. COVID normalized a degree of digitization that never can or will be rolled back barring grid collapse. You don’t have to read Ted K, I’ll paraphrase him for you: Technology does not crash, it creeps. It marches forward one step at a time, and it never reverts unless by force.

You can live like me in Texas where COVID has been functionally over since fall of 2020, yet even here many of us never returned fully to the world of atoms, having never realized we ever left it. Without our knowledge, we’d been pulled into the screen warp.

But there is a hopeful message in all of this: The degree to which you take part in or fall for the traps outlined above is entirely in your hands. No one forces you into the screen daily. And because the change became so extreme, it is also now more visible to those with eyes to see: this was not inevitable. You chose it. You were suckered into choosing it, but you chose it just the same. And so you can choose to reverse it. You are in control.

Dopamine feedback loops, once established, are hard to break. But it can be done: I’ve done it myself. I woke up in 2022 on the other side of the screen warp. But with discipline and self-awareness, I peeled my eyes away from the phone. (Spoiler: It didn’t take much more than agreeing to rough personal limits for myself then checking my iPhone’s screen time tracker throughout the day.)

Whether you want to own property, make money, find a spouse, start a company, master a craft…no number of Twitter followers, memes shared, forums perused will get you closer to those very real, non-digital goals.

Edging The Competition

Benjamin Franklin would write of his early printing years that he was able to be more productive, more effective, and better than his fellow printers because he didn’t start drinking beer first thing in the morning: instead, he drank only water or tea. While this small piece of daily discipline might have only improved his effectiveness by 10-20%, being 10-20% more effective than your peers give you a yearly 36-to-55-day edge (more productive effort per year).

The people around you are on their screens 20-30% more than they were in 2020.

This increase has not seemed to scale with any economic or productivity measures. I do not mean to imply that the purpose of life is to maximize billable hours, but rather some version of “progress towards goals by productive efforts.” Whether it’s building a family, a business, a house, a spiritual practice, or taking in the natural world you inhabit, losing 20-30% of your daily effort, attention, and most importantly time is a catastrophic loss to you in this, your one life.

I will return to social media, but never to uncritical screen use. If my life is a multisensory audiobook starting with my birth and ending with my death, I’d really like to avoid living it at 1.25x speed.

Tread carefully friends. Watch your hours, gauge how quickly your reality is slipping past.

Above all, remember that you are in control to choose your own adventure.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Our decadent elite cannot survive our technological transformation.

Our new technological environment is inescapable, as are the threats it poses.

The New York Times cancels social science in the name of social justice.