We don’t need a revolution to find political redemption.

Remembering Thomas S. Engeman (1944 – 2019)

Our teacher and friend trained us to find the safeguards of self-government through political philosophy and poetry alike.

We who were fortunate to be among Thomas Engeman’s graduate students at Loyola University of Chicago received with great sadness the news of his death on March 11, 2019. Prior to his career at Loyola, which lasted over 30 years, Engeman was an undergraduate at Cornell University, where his professors included Allan Bloom. During his final three years at Cornell he was also a member and ultimately captain of the lightweight varsity rowing team, which won Ivy League and national championships. He went on to enroll in the Claremont Graduate University, where he completed his Ph.D. after studying with professors including Harry V. Jaffa, Harry Neumann, and Leo Strauss. While in Claremont he coauthored Amoral America with George C.S. Benson, founding president of Claremont McKenna College. Before joining the faculty at Loyola, Engeman was also Leo Strauss’s research assistant at St. John’s College in Annapolis.

Throughout his scholarly career, Dr. Engeman examined fundamental political questions—the relation of the city and man, or of politics and philosophy; the dangers inherent in modern political philosophy, especially those connected to modern natural science; the imperative, as a matter of both principle and prudence, to defend liberal republicanism as the most reasonable, moderate modern regime; the corollary imperative to defend the Founders’ America against the corruptions of later strains of modernity incorporated through Progressivism; and the vital importance of poetry, in the broadest sense, as a means of cultivating and sustaining the moral and civic virtues that self-government in liberty requires.

Utopia and Progressivism

Among Engeman’s scholarly writings, his study of Thomas More’s Utopia is particularly subtle and profound, improving on the large body of scholarship that treated Utopia as a “celebration of the new order, written by a man canonized for his opposition to it.” Engeman showed More to be deeply schooled in the Platonic tradition, a master of the art of “civil philosophy[,] capable of saying different things to different people.” Utopia is then revealed to be a work of philosophic, comedic irony, with the imaginary Commonwealth of Utopia signifying, in fuller development, the modern society then emerging in Europe.

The character Raphael Hythloday, the founder of Utopia in the world of his imagining, is in turn the prototypical modern intellectual: abstractly humanitarian and cosmopolitan; ideological and dogmatic rather than genuinely philosophic; angry at injustice and moralistically intolerant; overbearingly confident and proud; and utterly lacking in prudence. In Engeman’s analysis, Hythloday prefigures the ruling class of Progressive elites, secular clerics of the faith that scientific administration is destined to prevail over democratic politics, disdaining the particular attachments that give order and meaning to most actual human lives. Hythloday and his Utopians represented the “Anywheres” described by Christopher DeMuth in the current Claremont Review of Books: partisans of cosmopolitan culture and open borders, consumed with sneering at the “Somewheres,” who exercise their right of democratic self-governance on the basis of affections rooted in family, community, and country.

Middle Class Mores

Much of Engeman’s later work defended the American middle class from the denigrations that pervaded popular culture, especially its portrayal in American literature. His essay on William Dean Howells expressed this concern with particular force. Literature, Engeman argued, could illuminate how American principles were conducive to healthy social practice, by depicting the “fragility of individual and family existence” and the importance of “religious practice” to the “maintenance of social morality.” Howells’s novels, Engeman liked to tell his students, could be read as “Tocqueville set to music.” Engeman’s scholarly papers on Willa Cather and John Updike both showed how religion was essential to overcoming the individualism and preoccupation to which Americans were susceptible. The Cather paper focused on The Professor’s House, Cather’s haunting novel depicting the spiritual confusion of Prof. Godfrey St. Peter, who was saved by his pious housekeeper, Augusta Ehrlich.

Similar concerns animated Engeman’s 2003 Claremont Review of Books essay “In Defense of Cowboy Culture.” Extending his argument that the average American was quite a bit better than average, Engeman vindicated the American variant of classic liberalism against Rousseauian critiques of it by Progressive intellectuals and Nietzschean critiques by conservative ones. Both disparaged American mores as contemptibly and unsustainably “bourgeois,” egoistic and materialistic, indifferent to any considerations above or beyond the self. Engeman, examining the same books and movies, found the basis of a broad and deep American admiration for heroic defenders of law and justice amid a dangerously disordered world, represented by the American western frontier. “By saving democracy’s frontier, the American knight-hero restores public confidence, ensuring the return of democratic law and order,” he wrote. “The renewal of public confidence, in turn, mobilizes the electorate for effective political action and reform.”

The American Regime

The American regime was also the focus of Engeman’s time directing Loyola’s Frank M. Covey Jr. Lectures in Political Analysis. These lectures yielded several compelling books that Engeman shepherded into print, including Michael Zuckert’s The Natural Rights Republic; his coedited book with Zuckert, Protestantism and the American Founding; and Robert Kraynak’s Christian Faith and Modern Democracy. The lecture series was just part of how Engeman helped create a serious academic culture among political philosophy graduate students at Loyola.

Constitutionalism was also a central preoccupation of Engeman’s career. His last published book, The Presidency and Political Science (co-authored with his dear friend and Loyola colleague Raymond Tatalovich), was concerned with how political science distorts and misunderstands the central institutions of American constitutionalism. The heroic presidency model, found in the work of Richard Neustadt and traceable to Woodrow Wilson’s own elevation of the presidency to a central place in the American constitutional order, had invested false hopes that presidents could provide the transformation of America’s political order—and encouraged presidents to see that as their task. The Presidency and Political Science argued for a “new realism,” contending that an institutionally limited presidency was more in line with the Constitution’s intentions and the republic’s perpetuation.

The Teacher

As a teacher, our friend conveyed in his own gentle manner the great themes of political philosophy and American political thought, by means of artful silence as well as speech. He asked probing questions and was content to await their answers, however long it took his students to venture them. He was often cryptic in his own declarative remarks, but in an inviting way, one that made the subject of political philosophy seem an endlessly fascinating puzzle. All this was a way of conveying high respect for those who enrolled in his classes, or showed up at his office. The recollection of studying with Tom, and learning the art of teaching from him, calls to mind a remark by Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws: “we must not always exhaust a subject, so as to leave no work at all for the reader. My business is … to make [people] think.”

We remember Tom Engeman, our teacher and friend, with admiration, gratitude, and affection.

Prof. Peter Myers, University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire

William Voegeli, Claremont Institute

Prof. Scott Yenor, Boise State University

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

“Thank God for being an American.”

Populists need to investigate the moral grounds on which ordered liberty is based.

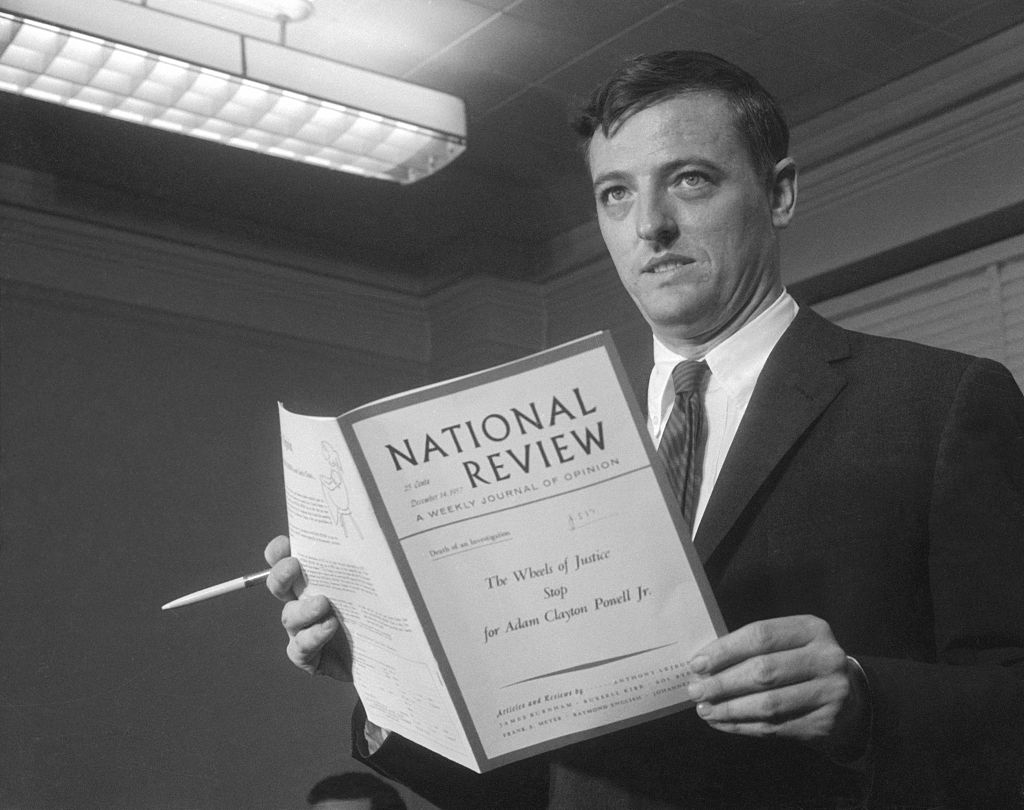

National Review's failure to grasp the friend-enemy distinction is revealing.

Leo Strauss and Russian Heideggerianism.

Four possible choices to defeat identity politics.