Unadulterated liberalism is creating a nation of unhappy scolds.

Racism, Inc. Finds a New Target

The new direction in anti-death penalty activism.

The knee-jerk anti-death penalty position of the woke elites is one of the more predictable aspects of their ideology. Just as predictable is the language they use to talk about it: “Racist, racist, racist.” Also “inhumane and torture,” but mostly “racist,” the coin of the realm in contemporary America.

The facts are otherwise, and voluminously so. There is no good evidence the death penalty is racist in application. Blacks are not disproportionately likely to receive the death penalty for no reason other than the anti-black biases of the system or its members. Blacks are disproportionately present on death row, but this certainly has to do with the fact that they commit a disproportionate number of murders.

Nevertheless, radical anti-death penalty activists seldom refrain from beating the tried-and-true old drum despite the evidence against them. Of late, though, they are taking up another tactic and arguing that racism is present not only in the processes that put blacks on death row but in the methods of execution themselves.

A recent NPR story, with the headline “States botched more executions of Black prisoners. Experts think they know why,” is indicative of the rhetorical trend. Its narrative is fully predictable given the source.

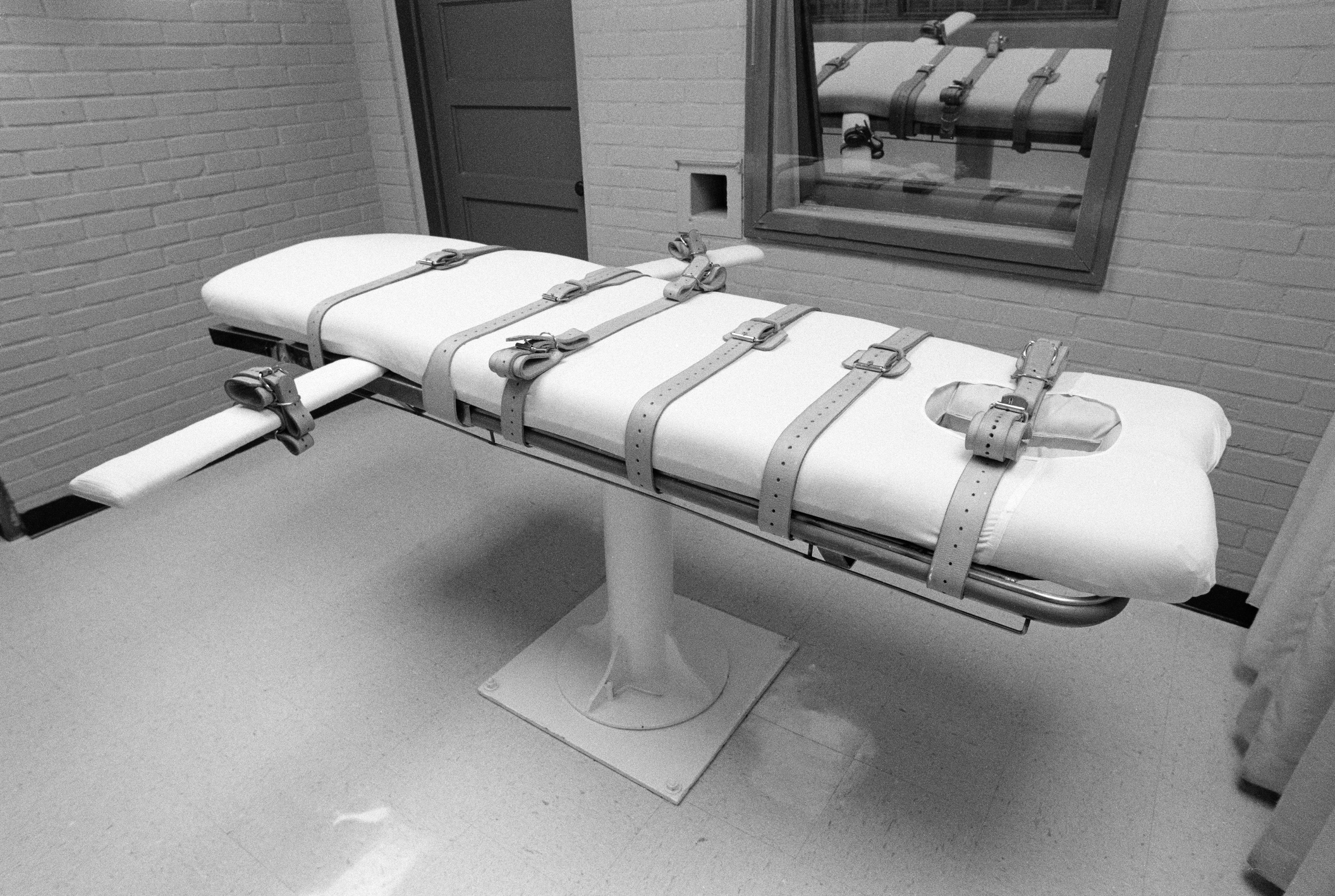

The source of the “new study” is Reprieve, an anti-death penalty activist group. They define “botched execution” in a manner that few objective observers would find convincing. If the convicted prisoner gave any indication of pain, or remained conscious after injection, or if the prison staff had even the slightest difficulty inserting the IV for administering the lethal drugs, the execution counts as “botched.” Over a third of lethal injections took at least 45 minutes, an intolerable offense in Reprieve’s view.

A Reprieve spokesman is quoted in the article, saying that “botching” constitutes de facto “torture.” It would be interesting to see how many Americans randomly selected from the population would agree to that description. It is an intriguing definition of “torture” that sounds, in at least some of its incarnations, rather like when you give blood at the clinic during an annual physical and the nurse has to jab you a few times. It hurt a bit, your arm bruised slightly for a day and two, and then you forgot all about it. That kind of “torture.”

The NPR report admits that the Reprieve “study” does not speculate as to why blacks are overrepresented among the “botched” executions, even though they make up a minority of the prisoners on death row (while still being overrepresented there given their makeup of the overall population). But they bring in some “experts” to speculate—and, of course, that speculation all runs to the same conclusion.

You can guess the institutional locations of these “experts.” One is Ruqaiijah Yearby, a professor at The Ohio State University who studies “racism in health care.” Here is her best analysis of what must be going on: “Black people don’t have thicker skin, we don’t have bigger bones…. But if you believe that, then you’re going to treat somebody differently than if you’re going to do it to a white person.” There is no evidence in the Reprieve study of this kind of differential treatment by race. But there is evidence that physiological differences among racial groups exist, and some of them might well lead to differential strategies for medical interventions in these individuals.

Blacks may not have “bigger bones” but they do have higher bone mass and bone strength than whites. There are also differential burdens for many diseases among racial groups, a fact well known to those in medical science. Sickle cell disease and the greater propensity of black women to get triple negative breast cancer, a particularly fast-growing and lethal variant, are well-established in the literature. The “expert” Yearby sounds here like someone who has not thought hard about this complex issue.

A second NPR expert, a criminal justice professor, engages in the following wild and wholly unjustified speculation: “You can’t find a vein and you think, well, it really is hard to find veins in Black people, so I’m just going to keep sticking.”

Finally, the NPR writer tells us of interviews he had with four workers inside prisons who have assisted at executions—that is, people who might empirically know what they are talking about. Three of those four, NPR is forced to admit, saw nothing that looked like racial bias on this matter. The fourth is “spiritual advisor Jeff Hood,” who claims he has seen blacks restrained more tightly than whites. Hood has no external verification of his claims, and NPR is of course uninterested in it. It is likewise not made clear how this might contribute to the likelihood of a “botched execution,” nor does Hood offer any insights into what black and white inmates might potentially be doing differently to merit the differential treatment he describes. The only thing that could produce these differences is racism, of course.

The NPR article does not make clear that Jeff Hood is described online as a radical social justice activist with a long record of anti-death penalty activism, specifically through a long association with the national anti-death penalty group Death Penalty Action. He claims to have written more than 70 books, including The Courage to Be Queer (the Amazon blurb of which states that “God is Queer”), and “his primary interest has always been in experimental theologies of liberation.” Of the four people NPR consulted with empirical insights on the question, Hood is the only one who parrots their preferred position.

Meanwhile, the typical observer of this situation might well have another question that is never broached in the Reprieve study or the NPR write-up about it: What did these men whose executions were “botched” do to end up where they were? The Death Penalty Information Center gives us some cases we might do well to examine in this light.

Joe Nathan James Jr., who was executed in Alabama in 2022, is commonly presented by activists as the typical case to illustrate their claims. James was supposedly “tortured” for three hours on the gurney. What actually happened was that initial attempts to insert an IV failed, and James was sedated for much of this three hour period.

But why was James on death row in the first place? The activists are typically uninterested in these details. James shot and killed his ex-girlfriend, Faith Hall, a mother of two young girls (at the time, ages three and six) who stopped the relationship due to James’s physical abuse. James stalked and harassed her for a period of months, often breaking into and vandalizing her home, banging on windows and sitting in the driveway. Several police reports failed to provide any reprieve from James, who had threatened to kill Hall numerous times and certainly made her life hell in the months before finally ending it.

This is the gentleman we are supposed to feel compassion for because he had to be sedated to be executed.

Another case of a black murderer whose execution involved “irregularities” the radicals have discussed publicly is Brian Keith Terrell, who was executed in Georgia in 2015. He stole and forged ten checks from an elderly male friend of his mother. The man declined to press charges on the condition that Terrell pay him back for the checks. Instead, Terrell shot him several times and then mercilessly beat him to death.

Here is a fuller description of Terrell’s crime, for the purposes of moral edification as to whom we are dealing with in this offender:

Terrell had his cousin drop him off at Watson’s house. According to court testimony, Terrell waited for Watson to come outside to go to his dialysis appointment and fired several shots at the older man. Watson was struck once in the leg by a bullet that ricocheted off the driveway. Terrell then reloaded and continued his attack. Terrell overtook Watson, struggled with him, shot him three more times, dragged him into some bushes at the side of the yard, and beat him brutally about the face and head, breaking bones in his jaw, nose, cheek, forehead, and eye socket and knocking out some of his teeth. The beating was so severe that bone penetrated into the victim’s brain.

The activists’ claim is that Terrell’s execution took an hour, and the nurse had to try several times to insert the IV, and that at one point Terrell winced at one of the attempts. A wince, in other words, is too much to bear in dispatching a brutal murderer of an innocent elderly man he had robbed and who showed him magnanimity by refusing to press charges.

There is little indication that the cultural elite obsession with whether a convicted murderer winces while being executed constitutes an intolerable offense against morality extends into the mainstream of America. Though the number of executions is steadily shrinking across the country, most Americans still favor the death penalty.

Interestingly, the Death Penalty Information Center, to which I link above as the source on the frequency of “botched executions,” and which admits it is an organization with a partisan bias against the application of capital punishment, shows a way forward that might both satisfy the American public’s general support of the death penalty and the radicals’ concern about “botched executions” and the suffering they purportedly produce. The one method of capital punishment that they list with a 0 percent botched rate is firing squad. Electrocution was several times less likely (less than a 2 percent rate) to produce “botched executions” than the current lethal injection methods, which were introduced largely because of the radicals’ concern about the inhumanity of the previous methods.

Perhaps if we want to satisfy the mixed demands of radicals and average Americans, we need to return to historically more effective methods for dealing with the most heinous of our criminal population.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Delegitimization of the justice system is a key step toward progressive domination.

Is California turning on its Jews?

Don't lose hope!

Postcolonialism rivals Jacobinism and Bolshevism in its systematic destruction of civil society.

Recovering statesmanship in an age of mediocrity.