The dark history of the radical Left's enforcement arm.

Postmodernism, Criminality, and Madness

On the crazy French origins of today’s crazy academic ideas.

In recent years, one frequently hears the charge by critics that much of what is presented to students in American college classrooms seems “crazy.” “Words are violence”; “Gender and even sex are social constructions with little or no basis in biology”; “All moral claims are relative, and so all ideas about law and criminality are too”; “Human identities are infinite and wholly personal, and nothing anyone does in the expression of identity can legitimately be classed as pathological.” The list of bizarre ideas now commonplace in higher education is long.

It turns out that there is more to the “crazy” descriptor than just a throwaway epithet. A good deal of the warped ideas propagated in today’s universities is the product of alienated, troubled minds that gave every indication of mental illness.

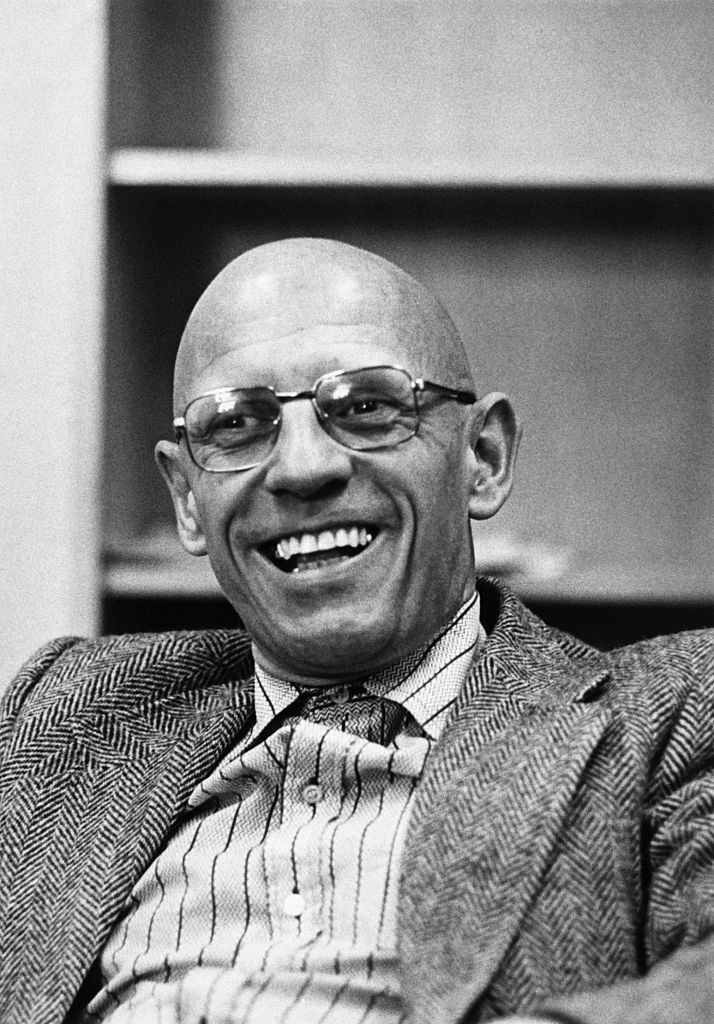

About a year ago, a story appeared that brought one of the most important radical thinkers of the late twentieth century into the vision even of those who never read him in a university. A former friend of the celebrated French philosopher Michel Foucault reported that Foucault had committed serious crimes of sexual abuse against children during his time living in Tunisia during the late 1960s. The allegation was that Foucault, a homosexual who died in his mid-50s of complications from AIDS and admitted having heavily participated in risky anonymous sex in gay bathhouses, was a “paedophile rapist” who paid young Tunisian boys for sex during an extended stay in the North African country, a former French protectorate.

The interest in this story for anyone with an eye on academic politics extends beyond the obvious moral and criminal issue of a French citizen apparently getting away with awful crimes against children. Foucault’s work—a good portion of which deals with sexual identity, criminality, and mental illness—has had a vast influence on leftist academic thought and teaching. Is there a relationship between this writing and the mental health of the individual who did it? And what might such a relationship help us understand about the current academic world, which takes the ideas of people like Foucault—and others in his influential radical cohort—on identity, mental illness and madness, and criminality so seriously?

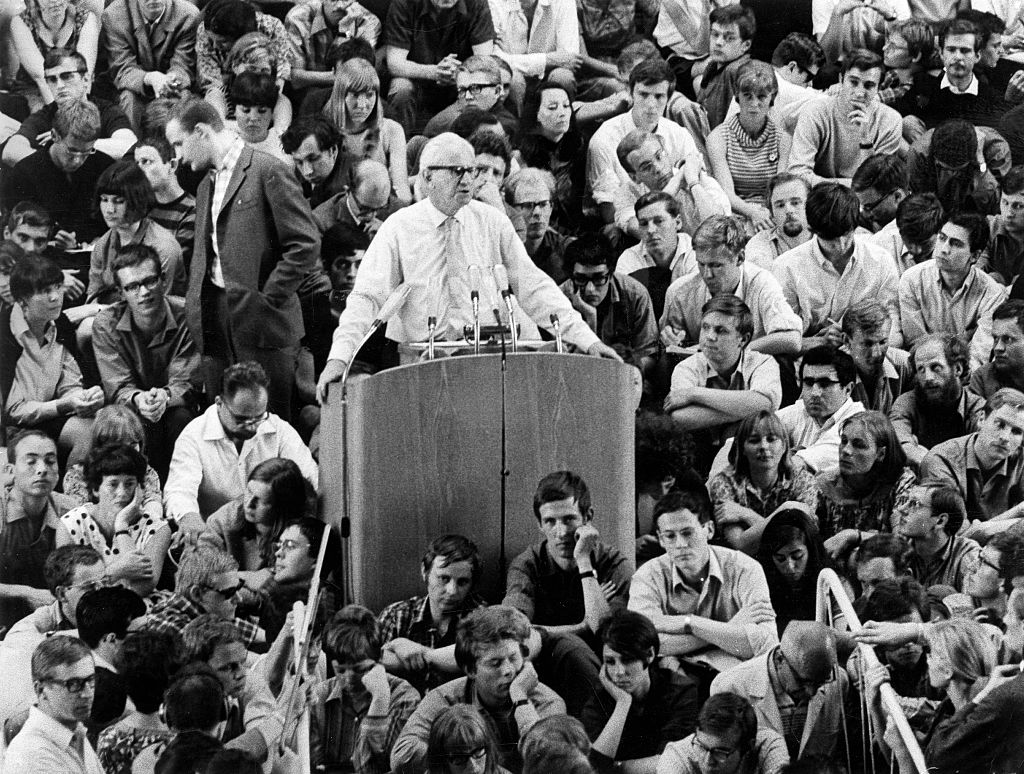

The question extends well beyond Foucault. A substantial number of the influential European thinkers who produced the literature on which much of the radical American professoriate draws for their teaching were no strangers to psychological pathology. One of the most evident and well-known examples is Louis Althusser, the Marxist philosopher who spent decades in the prestigious Parisian École normale supérieure, influencing generations of leftist students. Althusser was hospitalized numerous times during his life for mental breakdowns and was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia. He murdered his wife in their rooms at the ENS during a psychotic episode in 1980. Subsequently, he spent the final decade of his life as an inmate in a psychiatric hospital, ruminating on the possibility of receiving an audience with Pope John Paul II so he could instruct the Holy Father on how to prevent the Apocalypse.

The influence of Michel Foucault and his close friend Gilles Deleuze on American higher education has been considerable in every sphere in which postmodernism and poststructuralist philosophy has been important, including large swaths of the humanities and the softer social sciences such as anthropology and social psychology.

Foucault wrote several books on the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness. He argued that madness was a category of social control imposed on individuals who were not only not objectively ill but whose perspective on the world was uniquely privileged. Madness was created, in this analysis, by the power structure because it needed a new category of moral outsider to replace the vanishing figure of the leper. The madman was duly produced by the machinery of the social system to fill this role. There is nothing objectively wrong with the mental condition of the insane; they simply fulfill a need of the system of power relations.

Indeed, Foucault speaks of the criminally and violently insane in a language of exaltation and admiration. In his view, these people lurk in the borderland between the moral and transgressive and “establish the ambiguity of the lawful and the unlawful” through their words and deeds. Foucault believed the violent acts of such men could even constitute aesthetic works of tremendous creativity equal in their artistic importance to the great works of literature. He gave as an example Pierre Rivière, a young man in provincial France who murdered members of his own family in the 1830s and subsequently wrote a memoir about the otherworldly imperatives that compelled him to do so.

Foucault was gushing in his approval of the deed and the perpetrator’s writing about it: “Rivière’s own discourse on his act…so dominates … [and is] so strong and so strange that the crime ends up not existing anymore; it escapes through the very fact of this discourse held about it by the one who committed it.” Rivière was but one example of a multitude of infamous men who compelled Foucault’s attention. He sifted through the archival records of Parisian hospitals for the mad with the goal of documenting the lives of these “obscure men” who had been judged insane, criminal, or otherwise too dangerous to be permitted to escape incarceration.

Deleuze and his long-term co-author, the radical psychoanalyst Félix Guattari, made a similar contribution to the understanding of madness. They invented a philosophical system they called “schizoanalysis.” Its core was defined in the following terms:

Destroy, destroy. The task of schizoanalysis goes by way of destruction…Destroy Oedipus, the illusion of the ego, the puppet of the superego, guilt, the law…Destroying beliefs and representations…And when engaged in this task, no activity will be too malevolent.

Like Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari took up the task of recasting madness as something positive, an exceptionally acute view of the world to be embraced for its unique insights. They wanted to “undo … all the reterritorializations that transform madness into mental illness.” They foresaw an “age when madness would disappear.” As the very possibility of distinguishing the mad and the sane became impossible, all barriers between the categories would be collapsed: “[T]he exterior limit designated by madness would be overcome by means of other flows escaping control on all sides, and carrying us along.”

Deleuze is the author of a book-length study of the Marquis de Sade and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, the writers for whom sadism and masochism, respectively, are named. He referred to these pornographers as “great anthropologists…whose work succeeds in embracing a whole conception of man, culture and nature.” He celebrated their views for their disdain for law and for their advocacy of its “subversion…render[ing] laws unnecessary [by replacing] the system of rights and duties by a dynamic model of action, authority, and power.” This, Deleuze acknowledged, is a view of political society not unlike that proposed by the radical Jacobin terrorist Louis Antoine de Saint-Just during the French Revolution, a state of “free, anarchic action, in perpetual motion, in permanent revolution, in a constant state of immorality.” No laws, in this view, should be permitted to freeze the flow of social relations into a stable state. All should always remain in anarchy and chaos.

The author of these views committed suicide in 1995 by leaping from his apartment window in what one of his former students characterized perversely as his “final act of liberty.”

Foucault met his end in a different way, though it has been suggested there was in his demise too a self-destructive force at work. Much has been speculated about Foucault’s engagement in the homosexual sadomasochistic scene in San Francisco and elsewhere. He gave an interview with The Advocate during one of his visits to Berkeley in the 1980s in which he talked of the need to “create a gay mode of life,” which involved an embrace of the sadomasochistic “possibility of using our bodies as a possible source of numerous pleasures.” He also noted that certain drugs might be useful in creating such possibilities for pleasure.

In 1990, Hervé Guibert, a young writer who became a close friend of Foucault late in the latter’s life (and also died of complications from AIDS in 1991), created something of a scandal in describing Foucault in his novel À l’ami qui ne m’a pas sauvé la vie in the guise of a character named Professor Muzil. This shadowy figure leads a double life. By day, he is a mild-mannered professor at the Collège de France; by night, he is a violent and unbalanced pursuer of the most transgressive sexual pleasures imaginable in the leather bars and homosexual saunas hidden in the darkest corners of town. Guibert insinuated that Foucault/Muzil suspected his own positive HIV status and nonetheless continued his morally irresponsible adventures in the bathhouses, thereby certainly passing the virus along to an unknown quantity of other men.

The charge of pedophilia that fell on Foucault posthumously finds corroboration in his activism on this very issue. In 1977, a large group of the highest-profile leftist French academics were signatories to an open letter to the governmental commission to revise the penal code on sexual relations between adults and minors. Foucault and Deleuze played central roles in this effort. Other signatories included Althusser, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Jack Lang, Roland Barthes, Christine Buci-Glucksmann, André Glucksmann, François Lyotard, and the novelists Alain Robbe-Grillet and Philippe Sollers.

The signatories claim that the idea of nature as a framework for the moral understanding of sex and sexual relations is outdated. They asserted that no sexual interaction that is “without violence” should be made illicit by the state. Then, they set about defining what we in the West today typically recognize as child sex abuse as “without violence.” They argue that laws preventing sexual relations with those below the age of 15 are of a piece with laws against adultery and birth control. They assert that we must “recognize the right of the child or the adolescent to have sexual relations with the person of his choice.”

Foucault and Deleuze also believed that incarcerated prisoners were broadly victims of illegitimate oppression and worked to facilitate moral reevaluation of their crimes, especially sexual and violent crimes. They were instrumental in the creation of a radical prisoner advocacy group, the Groupe d’information sur les prisons (GIP), or Prison Information Group. Deleuze, joined by Foucault’s partner Daniel Defert, described the suicides of prisoners accused of acts of sexual aggression and perversion as admirable and radical acts of resistance to the repression of the prisons. The two chronicled the case of a prisoner who had taken his own life after being placed in solitary confinement for having sexually assaulted other inmates. Deleuze and Defert argued that the prison officials were “personally responsible” for the death due to the stigmatization of sex between prisoners. This was all consistent with arguments Deleuze, in collaboration with his colleague Guattari, had made in criticism of what they saw as the criminalization of desire by mainstream French institutions.

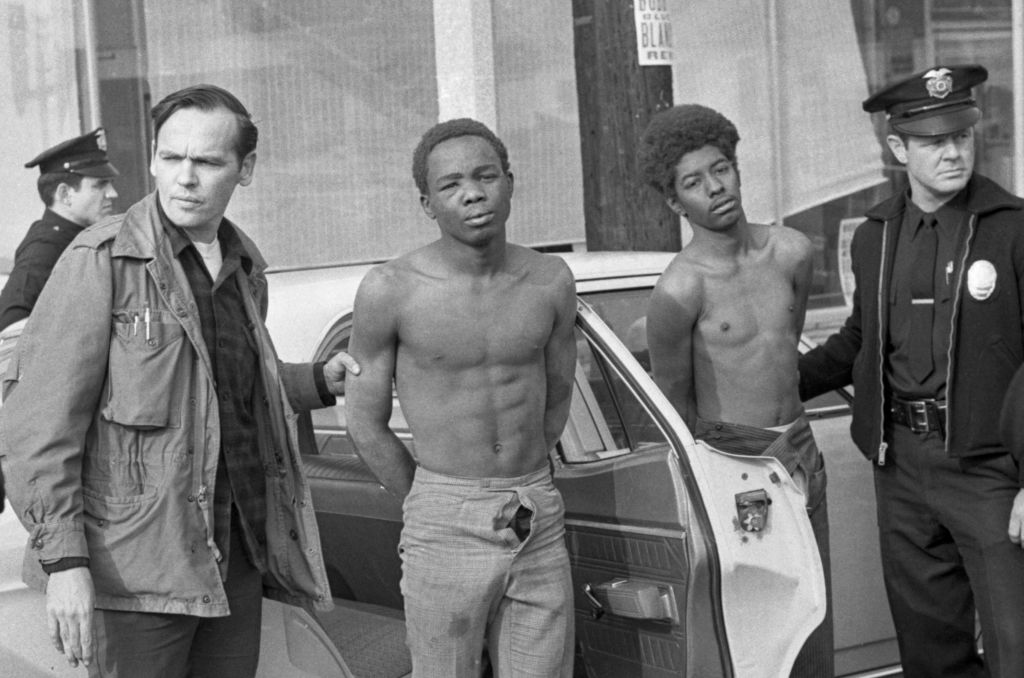

The GIP also tied itself to the radical race politics of the era in a way perfectly consonant with the most extremist anti-police discourses we hear in universities today. One entire issue of the GIP’s newsletter, Intolerable, was dedicated to the death of George Jackson, a Black Panther militant and convicted felon fatally shot in August 1971 during an attempted prison break. Jackson, who was awaiting trial on the murder of a prison guard that he allegedly admitted having committed, had been smuggled a pistol by a member of his legal team and used it to take several guards hostage. He subsequently killed them before making his doomed escape attempt. Deleuze described Jackson in glowing terms of admiration as a “political prisoner” whose death was necessary because the system recognized that, as “one of the first revolutionary leaders whose entire political formation took place in prison … [and] also the first … who analyzed prisoners as a class and assigned them a specific role in the revolutionary process,” he posed a serious threat to the racist prison system. Violent incarcerated felons, that is to say, were seen by these thinkers as an oppressed class who could be understood most effectively with a remade, distorted Marxian theory in which they became the revolutionary proletariat.

One final, less well-known bit of Foucault’s work further augments the picture depicted here, for it shows what a delusional political view extended from his moral perspective. In the fall and winter of 1978-79, he wrote several articles for the Italian daily paper Corriere della sera and one for Le Nouvel Observateur reporting on the events in Iran that produced the Islamist regime still in power there. Foucault admitted to knowing little about the country prior to taking on the assignment. He met with Iranian revolutionary figures residing in Paris and spent two weeks in Iran during the fall of 1978, interviewing members of the Islamist movement.

It is a tremendous understatement to note that Foucault utterly misjudged the situation in Iran. He believed Shi’ism was by its structure—“absence of hierarchy in the clergy, independence of religious leaders with respect to one another, but dependence (even financial) on those who listen to them, importance of purely spiritual authority”—less predisposed to the traits generally associated with Islamic regimes. Shi’ism would perhaps, Foucault argued, “allow the introduction into political life of a spiritual dimension.”

The terms Foucault used to describe what was happening in Iran are fascinating in their deluded admiration for the emerging new regime. The Islamist revolution constituted, in his view.

an inner experience, a sort of constantly recommenced liturgy…it has brought out…an absolutely collective will…in rising up, the Iranians said to themselves…“[A]bove all, we have to change ourselves. Our way of being, our relationship with others, with things, with eternity, with God, etc., must be completely changed”…[R]eligion for them was like the promise and guarantee of finding something that would radically change their subjectivity.

Incredibly, he imagined that what was happening in Iran in 1978 and 1979 was the “first great insurrection against…the weight of the entire world order.” The great communist revolutions of the twentieth century had failed to bring utopia, but Foucault believed perhaps the Islamists would correct the errors of the Leninists, Stalinists, and Maoists.

When I was a graduate student in the 1990s, familiarity with the work of Foucault and Deleuze was de rigueur for membership in and interaction with the circles of the academic left. This was true across disciplinary boundaries. I was trained as a social scientist, but I knew many Ph.D. students in humanities disciplines who were similarly immersed in these ideas. They are now taught to undergraduates. Still more commonly, their ideas are presented in slightly revised forms by those same graduate students of a generation ago who are now doing the undergraduate teaching.

Here, then, is a brief on the derangement of the moral and political frameworks presented in the work of two of the most influential European radical thinkers of the late twentieth century and a case that those frameworks were rooted in lives of alienation and psychological suffering. Their ideas survive and are taught in many of the college courses, by many of the college professors, who today, long after the deaths of Foucault and Deleuze, adhere to the same distorted view of human life and society. Those who flippantly refer to these ideas as “crazy” are on to far more than they know.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Radical Left currents run deep here at home.

The Left has always worshipped violence, so its recent exuberance is no surprise.

From the Black Panthers to Hamas, the radical Left loves to lie about terrorist groups.

The suicide of Aaron Bushnell indicates that the military has not purged itself of dangerous ideologies.

Professional, ideological, and even familial ties connect American institutions in a web of leftist influence.