Eighty years of diversity and equity have destroyed a nation.

Breakfast for the Kids

From the Black Panthers to Hamas, the radical Left loves to lie about terrorist groups.

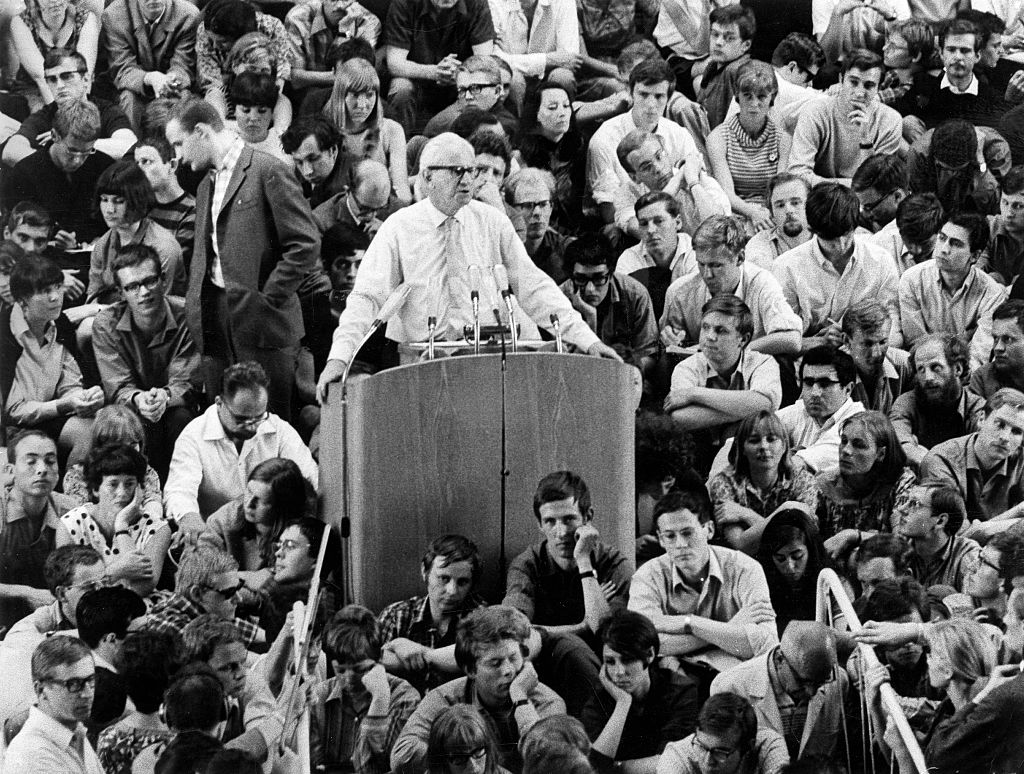

One of the most intriguingly depraved of the many insanities of radical college faculty in our time is the effort, now ongoing for decades but increasing in intensity and expanse in recent years, to rehabilitate the Black Panther Party (BPP). For a good while in the wake of the demise of the BPP in the early eighties, they were anathema even to much of the Left, as the outspoken embrace of violence by this Marxist-Leninist criminal youth gang masquerading as a political movement was seen as beyond the pale even to staunch progressives. As we got farther away from the BPP, though, the radicals began an attempt to establish respectability for them, in the popular culture and especially in higher education, confident that nearly all the students they teach today will be wholly historically uninformed about the BPP story and too lazy to do any research on them.

The BPP or one or another of their central “thinkers” (Huey Newton, George Jackson, Angela Davis) are now the subject of many courses in universities and colleges. Even at the small liberal arts university that employs me, there is a growing collection of such courses being taught, mostly in Critical Black Studies and History.

One popular narrative under construction on the academic Left at present about the BPP involves their efforts to set up “free medical clinics.” As I was walking around near the History Department the other day, I came across a poster for a course that evidently engages with just that piece of BPP history.

The line in such courses, as evident from the image the poster for the course reproduced from a BPP document of the 1970s and from the course’s assigned reading, is that a significant part of the group’s political work was in the form of providing free medical care to needy blacks, which they could not obtain from racist America. And, the narrative goes on, this program was a remarkable success, bringing competent, quality medical care to a community that could not otherwise get it.

One of the books frequently used in courses that treat this topic, which is assigned in this course, is Alondra Nelson’s Body and Soul, a stellar example of the de facto propaganda that is produced by academic Black Studies. In a thin book of less than 200 pages, including notes and bibliography, Nelson provides remarkably little on the actual details of the BPP’s health clinics. Only part of one chapter gets to any degree into these details. There is an obvious reason for this absence, and it is that what these clinics did in the way of significant health service for the communities in which they briefly existed was next to non-existent.

As Nelson herself admits, much of what went on in these “health clinics” was political propagandizing, essentially a full-court effort to introduce volunteers and patients at the clinics to revolutionary communist thought: “The Party…sought to ‘reeducate’ the medical professionals who partnered with them by exposing them to the ideas of Mao Zedong, Frantz Fanon, and other political thinkers…. The political reeducation that the Party required of its expert collaborators was intended to build a bridge of understanding.”

What was done in the way of real medical services in these clinics, and who provided the services? The answers are both underwhelming and concerning. Most of the staffing, Nelson acknowledges, was provided not by volunteers with any medical or nursing training, but by existing BPP members. The level of volunteer participation by those with any medical expertise at all was tiny from the beginning, and it shrank to virtually nothing after the brief enthusiasm at the opening of the first clinics. Most non-BPP member volunteers were untrained progressives and radicals from the surrounding communities who agreed with the Panther’s politics but had no knowledge of medicine or health care. “We would train them to work to some extent like paramedics or physician’s assistants,” explains one former BPP member. “We actually trained some of the women to do pelvic [examinations] and gonorrhea screening…. You had a lot of sharp people who learned things very quickly.” In other words, what the BPP clinics were providing was “health care” by people off the street with no formal training.

The level of services provided was, for this obvious reason, greatly restricted. At their most advanced, the clinics took blood pressure readings, checked lead levels in blood, screened for diabetes, provided basic treatment for colds and flu, and gave a few basic immunizations. We do not know how frequently these ill-trained non-doctors and non-nurses made mistakes in these basic services and harmed patients, but the former BPP members Nelson interviewed admitted they “couldn’t handle anything very serious.” The rhetoric about the marvels of the BPP clinics is nonetheless unrestrained in radical circles today.

In addition to their difficulties recruiting actual medical professionals, the BPP also had trouble procuring equipment needed for even their minimal level of operation. This equipment “was begged, borrowed, purchased, scavenged, and sometimes just appeared on the doorstep.” Left out of this litany is “stolen or strong-armed.” The BPP was notorious among neighboring businesses for their ability to extort “donations” to their operations under implicit threats of vandalism and violence.

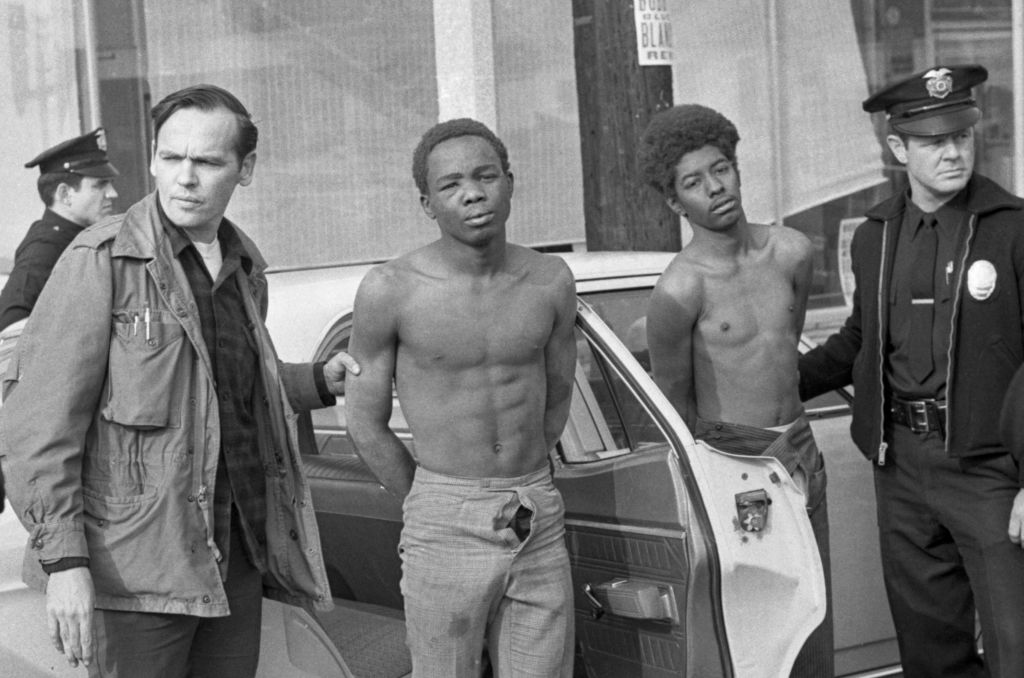

Even sources advocating the lie of the great contribution the clinics made to health in the communities affected occasionally provide insights into the truth, albeit mostly under their breath. Here, for example, an advocate admits: “Unfortunately, [Party Free Medical Clinics] were often harassed by city health inspectors, subjected to police raids, and had difficulty maintaining consistent volunteer medical staffing. These multiple problems led to the gradual closure of all PFMCs except for Seattle’s clinic.” Why might health inspectors have been harassing the clinics, and why were the police raiding them? The answer is because the clinics were typically an unsanitary mess. In order to avoid being recognized by authorities as the health threat they posed to the people who came to them through possible exposure to infection and disease, the BPP refused city and state inspectors access to the clinics.

Nelson admits, though fleetingly and without much elaboration, that the clinics “refused to apply for a license from the health board to dispense healthcare services because doing so would have permitted city [health] inspectors to make at-random checks at the clinic.” Police raids were certainly tied to the array of criminal activities that the BPP was operating, from extortion from local communities to drug dealing, frequently under the aegis of its “breakfast programs for children” as well as that of the medical clinics, as the BPP leadership calculated that such innocuous-sounding programs might be more likely to be overlooked by law enforcement.

Baseless propaganda about the BPP as a liberatory and successful alternative method of health care for the black poor is what is being taught as “history” in our colleges and universities. And the mainstream press takes every opportunity to spread the lies beyond the halls of the ivory tower. Time cites Mary Phillips, a professor of Africana Studies, explaining that “many people think of [the Black Panthers] as criminal thugs, and that’s far from the truth. The Panthers were not about violence. They were actually about restorative care. They were actually about healing the community—mind, body and soul.”

The concern for restorative care must be why Huey P. Newton, the co-founder and leader of the Panthers, was seen by witnesses as he shot and killed Oakland police officer John Frey, only later to have the conviction overturned on a technicality; and it’s why Newton later killed a prostitute who called him a name he didn’t like, and also tried to murder a witness in the case; and it’s why Newton talked endlessly about the necessary role of violence in the revolution he desired. “And people say, well Huey you’re so violent. Why are you so violent, Huey? You engage people in such violent rhetoric. You sit up talking about spears and penetration and stabbing people with toothpicks. And I say, well hey, existence is violent; I exist, therefore I am violent in that way.”

And the desire to “heal the community” is what drove Bobby Seale, the other BPP co-founder, to orchestrate the torture and murder of a fellow Panther, Alex Rackley, and it’s why he, like Newton, spoke constantly about guns and violence as an essential part of his revolution, e.g.,: “It’s damn near time we picked up the gun to try to begin to get some peace.”

And “healing the…mind, body and soul” is why Eldridge Cleaver, another Panther leader and a convicted violent felon, set up ambushes of police officers as a systematic practice of the Panthers, and gave birth to the Black Liberation Army, a still more radical group that targeted police for assassination, and it’s why he, like Newton and Seale, talked incessantly about violence, even claiming that his serial raping of white women, for which he did time in prison, constituted “an insurrectionary act.”

And this is why George Jackson, another important figure in the Panther pantheon and, like Cleaver, a convicted violent felon, spoke constantly of violence, writing, among other gems, the following paean to murder: “There are many thousands of ways to correct individuals. The best way is to send one armed expert. I don’t mean to outshout him with logic, I mean correct him. Slay him, assassinate him with thuggee, by silenced pistol, shotgun, with a high powered rifle shooting from 400 yards away and behind a rock. Suffocation, strangulation, crucifixion, burning with flamethrower, dispatch by bomb.” And it’s why Jackson died trying to escape from prison after being smuggled a gun by his radical attorney and killing numerous guards and fellow prisoners before falling himself from a prison sniper’s bullet.

And it’s why the Panthers had children singing songs with lyrics like “Pick up the gun and put the pigs on the run!”

And it’s why Panther rallies often chanted things like “The Revolution has come, off the pig!, it’s time to pick up the gun!”

Because they were not about violence, even though they said and did all these tremendously violent things. Because they are “actually about restorative care.”

This is what the radical professors ask their students to believe today.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Radical Left currents run deep here at home.

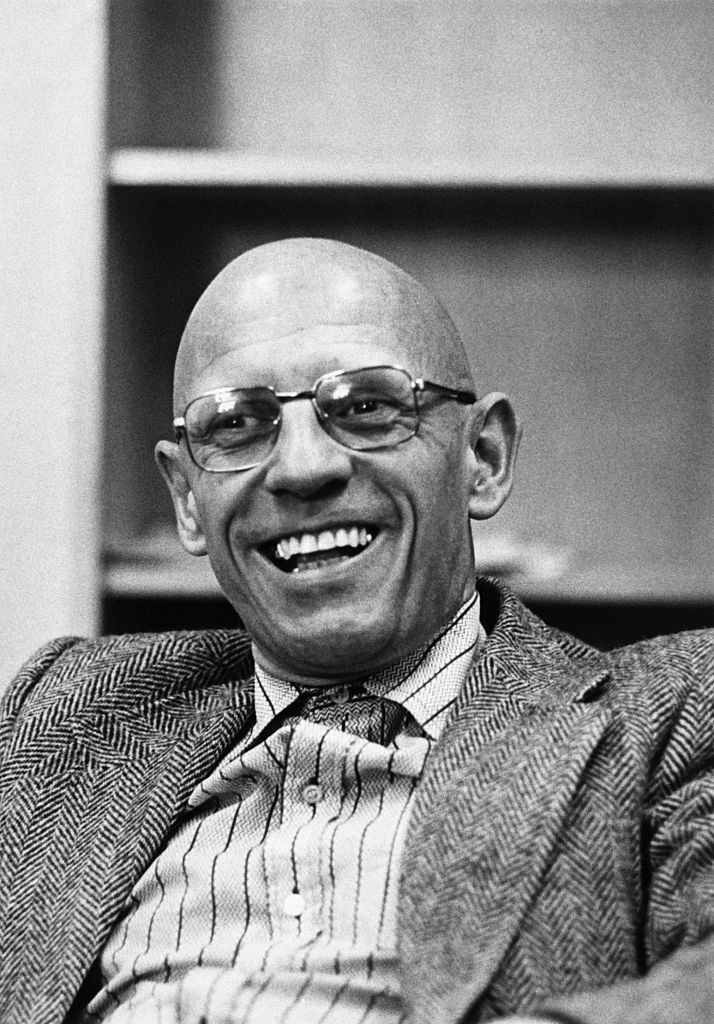

On the crazy French origins of today’s crazy academic ideas.

The dark history of the radical Left's enforcement arm.

The collapse of academic standards is a function of racial preferences.

If they don't act, white Americans will soon be subsidizing their own destruction.