Marcuse, the American Philosopher

Radical Left currents run deep here at home.

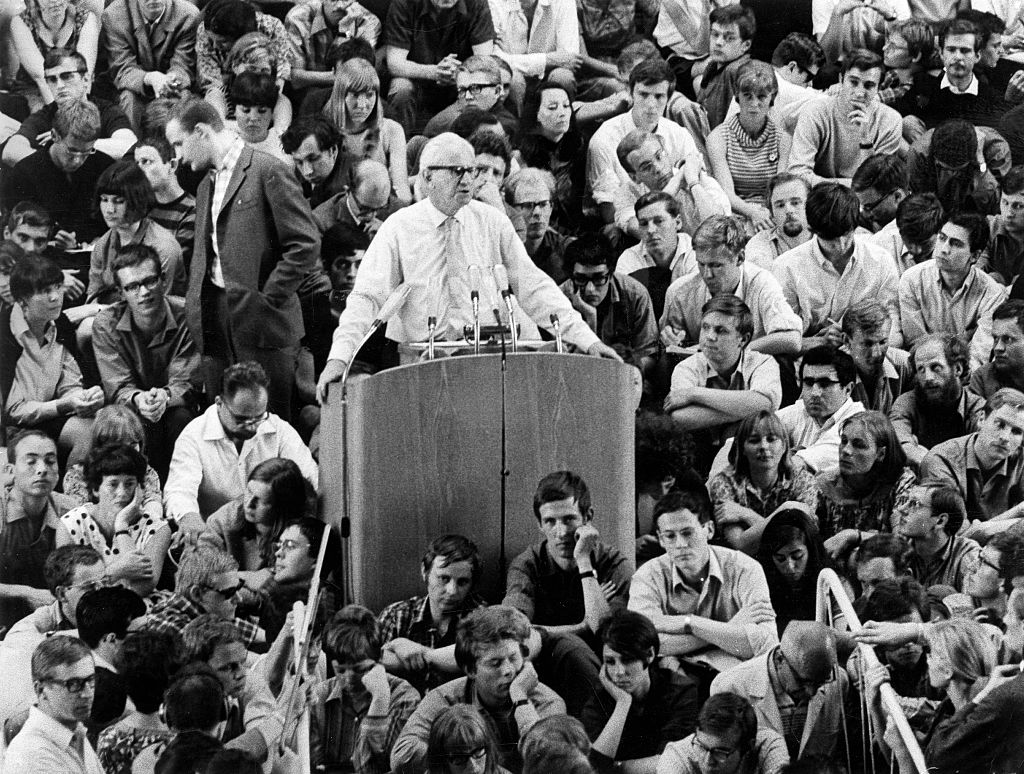

Christopher F. Rufo recently published a bestseller on the impact of predominantly foreign leftist ideas on American politics and culture. In his review of the volume for the Washington Post, Hugh Hewitt compares Rufo’s considerable work to such examples of “intellectual history” as the political tracts of George Will, Matthew Continetti, and Jonah Goldberg. As a trained intellectual historian, I raised an eyebrow when I encountered Hewitt’s idea of historical studies that are “well done” and “full of illuminating ideas.” Also, Hewitt used the space allotted to him to attack my favorite graduate professor, Herbert Marcuse, a large photograph of whom graces his review. My former mentor functions in Hewitt’s account largely as a whipping boy.

According to Hewitt, Rufo focuses on Herbert Marcuse, “whose Marxist- and Freudian-inspired critical social theories had an astonishing lasting impact on the American left.” Among the notorious activities of this German refugee scholar, who came to the U.S. in the thirties, was training Angela Davis, the black radical Marxist, and this relationship (as we are not told) came during the twilight of Marcuse’s career, at the University of California at San Diego. Hewitt believes that though Davis was a “marginal figure in the violent upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s,” her complicity in the attempted escape of murder suspects in a courtroom drama in Marin County, California, which resulted in four deaths, was somehow related to Marcuse’s teachings. Hewitt, like Rufo, does mention homegrown radicals like Derrick Bell, the first black law professor at Harvard, but the major focus for both the author and reviewer is the poisonous fumes of foreign ideologies, particularly the radical revolutionary doctrines of Marcuse.

Although it is not my intention to deny such influences entirely, I believe the American conservative establishment has focused excessively on foreign contaminants while denying the extraordinary receptiveness of American political culture to certain European fashions. Works by conservatives attacking Marcuse and his followers as “termites” eating away at the otherwise sound structure of American democracy go back to Eliseo Vivas’s Contra Marcuse in 1971. This work by a prolific Colombian American aesthetician, which offers a penetrating critique of Marcuse’s social theory, gives the impression that nothing essentially American was responsible for the spread of Marcuse’s ideas. We were taken unawares, runs the argument, by dangerous foreigners whom we let into our country out of misplaced generosity.

Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, which became a conservative bestseller in 1986, does not dwell on Marcuse, but Bloom looks critically at other alien ideas that he believes polluted the real America. These ideas entered our culture through “the German connection,” and apparently college students, according to Bloom, were becoming radicalized after devouring Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger. Though Bloom’s central argument seems to beg for evidence, it had the indisputable advantage of not blaming what was indigenously American for the straying of American political culture. A patriotic reader could deplore our radicalization without having to believe that what was taking place was owing to things originating at home.

My own view in this matter, to which I devoted several books, argues the opposite position, namely that there were already developments in the U.S. that led to the breakdown of our traditional social and political institutions. There is no need to point to foreign contaminants to explain our condition. Frankfurt School theorists like Marcuse, Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer acquired fame and fortune in American exile. They only acquired comparable status in their native Germany with the American post-World War II occupation, when the American government sent critical theorists back to “reeducate” the Germans.

In the U.S., as Christopher Lasch argues persuasively in The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics, what were considered radical social ideas in interwar Germany, e.g., massive social engineering, the imposition of gender equality, the acceptance of homosexual relations, and a continuing crusade against the “fascist” mentality, resonated nowhere else as well as they did here. The Authoritarian Personality, which Adorno and Horkheimer coedited in 1950 and which was published by the moderately left-of-center American Jewish Committee—which, by the way, also put out Commentary—became a standard work in the social sciences. The F-scale devised by Marcuse’s friend Adorno for determining “pro-fascist” attitudes was adopted in both the U.S. and Canada as the basis for testing the mental soundness of students and public administrators. The highly respected social scientist Seymour Martin Lipset viewed The Authoritarian Personality as a valuable guide not only for understanding the fascist danger but also for mobilizing Western democracies against Soviet Communism.

By the time Lipset offered this judgment, members of the Frankfurt School had run afoul of the House Un-American Activities Committee for having leaned too noticeably toward the Soviets during the Cold War. This however may be less relevant for our consideration than the widespread cultural and social acceptability in the U.S. of what in interwar Germany had been considered “cultural Bolshevism.” In the U.S. the founders and early members of the Frankfurt School, including psychologists Eric Fromm and Karen Harney, found an enthusiastic home.

By 1968, when Angela Davis was studying with Marcuse in San Diego, her teacher had become much more of a political activist than he had been when I first encountered him five years earlier. In the intervening time, events occurred which may shed light on this change. Brandeis University had refused to extend Marcuse’s professorship beyond the fixed age of retirement; and Yale, while I was studying there, turned down the plan to offer this dignitary a special chair in the history of Marxism. I suspect Marcuse took the offer from San Diego because nothing better came his way. It is also hard to recognize from Davis’s descriptions my own professor, although I have no doubt that after my relationship with him, he became more negative about Western “repressive capitalism.”

In one of Marcuse’s classes I attended, many of his students were patriotic anti-communists. I myself have not changed my political opinions significantly since that time, but I don’t recall Marcuse ever trying to censor or cancel any of us in class for not parroting his political convictions. We assumed what his opinions were since he never stated them explicitly. To my surprise Marcuse liked Joseph de Maistre’s profoundly reactionary dialogues, Soirées de Saint Pétersbourg, which he could quote from memory, while naming different editions of that work. Compared to my other professors, who were mostly pedestrian liberal Democrats, Marcuse stood out as an old-world scholar.

In the sixties, the U.S. underwent enormous political ferment, which likely would have been the case even if political activists were not reading Marcuse, Franz Fanon, and other non-American radicals. The antiwar and civil rights movements and the burgeoning of the feminist rebellion against a male-dominated society were all taking place simultaneously. Meanwhile the administrative state was assuming a larger and larger role in fighting “discrimination” and righting what were perceived as historic wrongs. There was also a movement in the counterculture that rejected bourgeois standards of social conduct, and which was open to both sexual promiscuity and psychedelic experiences. European thinkers like Marcuse definitely influenced those fashions, but they were not necessary for their flourishing. It is quite conceivable that most of these developments would have transpired even without the effect of European radical thinkers. There was enough combustible energy in the U.S. to have produced these results without foreign stimulants.

Moreover, Europeans were reading American progressives like Betty Friedan, Paul Goodman, and C. Wright Mills while Americans were reading European radicals. The radicalizing influence was certainly not all in one direction, as I noticed from visiting European bookstores in the sixties and seventies. Rufo’s subject, Marcuse, became in some sense an American author. His books were published in English for American readers from 1941 onward, which was the date of the appearance of Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory. (A German edition of this work did not exist until 1962.) Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud came out in English in 1955 and was then translated for German readers two years later. One Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society was also first produced in English, for a predominantly American readership, in 1964, and wasn’t available in German translation until three years later. Marcuse’s An Essay in Liberation was likewise published first in English in 1969, although the German version Versuch über die Befreiung came out shortly afterwards.

I mention these publication dates to indicate where Marcuse’s primary audience was found for decades. No one would deny that he came from a German cultural world and spoke with an accent. But he found a fervent fan base here long before he became a rockstar in Europe. Already by the seventies, I no longer thought that the U.S. was being transformed by an invasion of foreign authors. I realized that the cultural and social changes that we were experiencing were mostly internally generated. European radicals resonated with American academics, journalists, and college students because they fitted in with what this country was becoming. The success story of the “American” Herbert Marcuse is a case in point.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Root, root, root for the electors. If they don't win it's a shame.

Part I: Unfettered reason cannot conserve anything.