Democracy and despotism in a digital age.

How to Take Back Your Soul

At the National Conservative Conference, a vision of Christian humanism.

In Rome, at the second National Conservative Conference, two speeches were dedicated to the defense of humanity from the onslaught of progressive ideology. This ideology has been best (and most succinctly) described by The American Mind’s own James Poulos as the Pink Police State.

The call to action was first articulated from an American perspective by the man who kicked off the proceedings, Rod Dreher. It was then reiterated in a very different French context by Marion Maréchal.

Comparing the two speeches and speakers, I was surprised that they should agree on so many points—I think Rod would agree as well, since he was impressed with Maréchal’s speech and talked to her about it privately. But then again, it’s surprising that they should have met at all. Rod is an American Orthodox—former Catholic—in favor of small communities, whereas Maréchal is a Catholic overflowing with visions of a Europe redefined as a French Empire!

But both see the same enemy—globalized Progress—and the same saving grace—Christianity. Both look toward a renewed interest in anthropology and ecology in order to save humanity from the trans-humanist future. Maréchal pointed to the late Sir Roger Scruton’s belief that conservatism is all about the oikos, the home, which should guide both ecology and economics. Only at that level can we develop an anthropology, an understanding of what makes us human, that shows what’s distinctive and irreplaceable about us.

Maréchal, interestingly, presented herself as a new Jeanne D’Arc, ready and willing to face off against a new enemy trying to destroy the French way of life. Her vision of change goes to politics through the culture and seems strangely religious—strangely because as she herself insisted, the French are anti-clerical, though Catholic. Her presence at the conference suggests she is indeed preparing to return to French politics at the highest level, and her politics will be one of national deliverance.

We may compare Maréchal’s Jeanne D’Arc with another figure from the Christian Middle Ages: Dreher’s own self-chosen patron, St. Benedict of Nursia, founder of the order that bears his name and of a kind of community that would prove essential to saving civilization in times of barbarian invasions. The two have this in common: their admirers would call them visionaries and their detractors fanatics. They are not normal politicians and they can only address abnormal times.

Rod discussed his upcoming book, about how Catholic Slovaks resisted Communist persecution by taking the “Benedict option”—organizing communities that could take strength from the catastrophe of the times. Here we begin to see what it might take to fend off the therapeutic-pharmaceutical Pink Police State: Communities that can educate, summon, and reward the courage to face suffering, to live uncomfortably, to be disciplined rather than lazy—that is, to have a transcendent purpose for which to live.

Refounding and Community

Both speeches were about some kind of founding and both carried the suggestion that what we now need is a change of character at the level of a renaissance. In Rod’s case, going back to the Middle Ages and pointing out that it’s been done before successfully offers great clarity about the model Christian conservatives should follow in order to live by prayer. They have to prepare to withstand persecution. To organize parallel communities that can offer jobs, education, fulfilling lives, as well as legal defense.

In Maréchal’s case, she described a revival of Christendom under new conditions, a way of life that would safeguard people and preclude the need for such hardship—or perhaps the outcome of a political conflict where such communities eventually prove victorious—but she was far more vague about what that community might mean. Despite talking about phenomena at scales as different as village and empire, they had the same idea about the need to redirect our attention from the abstract, vague, and universal to the concrete, particular, and knowable.

In philosophical terms, we call this love of one’s own. Without an interest in inheritance, even in the form of a renaissance, a taking into possession anew one’s long-lost or buried heritage, loyalty is not possible. Without loyalty, a community where people hold things in common is not possible either. The name for that kind of relationship is honor—the requirement that deeds should live up to speeches and the promise that people can rely on each other to be known and loved.

It is not, therefore, accidental that these two visionaries of a new Christianity should meet at a conference about nationalism. Inheritance has something to do with politics—with the requirements of acting on our political nature. Honor is a strange word in modern politics. If it were to find its way back into our everyday speeches, that would be an important sign that these speeches are right, that we are recovering what we have long been missing.

Accordingly, the big promise I see Rod and Maréchal make is: if you follow this new path, you get your soul back. You are no longer merely a patient of a new medicine that treats your interest in yourself as a disease to be cured—no longer the lab rat of vast experiments run by elites who neither subject themselves to the same dangers nor admit to any share in a common nature that would make consent and deliberation necessary.

But aside from the political use of the soul, there is another one, which is much more personal. The appeal of national conservatism, or of Christian visionaries, is at this point limited. But the appeal of other vague things that hint at similar promises, from Joe Rogan to Jordan Peterson, is wide, if shallow, and therefore points accurately at the great need so many young men and young women feel to redeem themselves.

This is why political change is underway. Though I cannot myself predict how it will turn out, I’m sure there’s a need now for this new form of Christian community and for this new Christian vision of bringing people together to complete their commitments and arouse their better aspirations. Maréchal’s statement that we need a new anthropology to fight off trans-humanism is the best statement the soul-searching so many people are engaging in. This might define our generation.

There’s some reason for hope in all this. Comparing the two speeches, it became obvious to me that the Christian commitment is the core of the confidence to face down the Pink Police State. Should you choose to disobey scientific-gnostic authorities that try to redesign your body and want your mind to be at peace through meditation and marijuana, how are you going to find another authority that will preserve your humanity? That’s the question now.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Debunking a contradiction in terms.

Libertarianism again fails natural right.

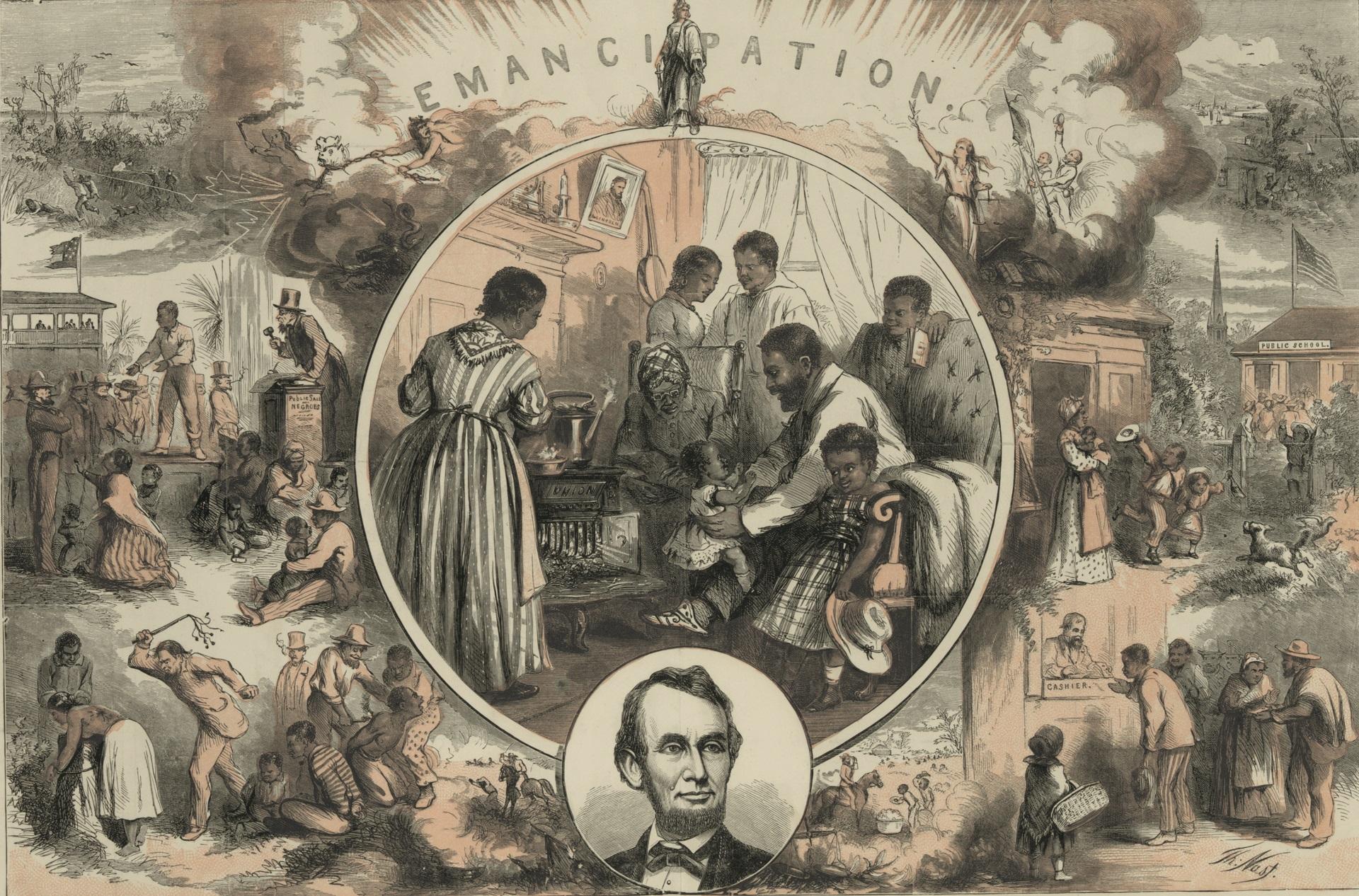

Revisionist Black supremacist history can't grasp our shared equality.

In a collapsing age, humor and spirit alone won’t do us justice.