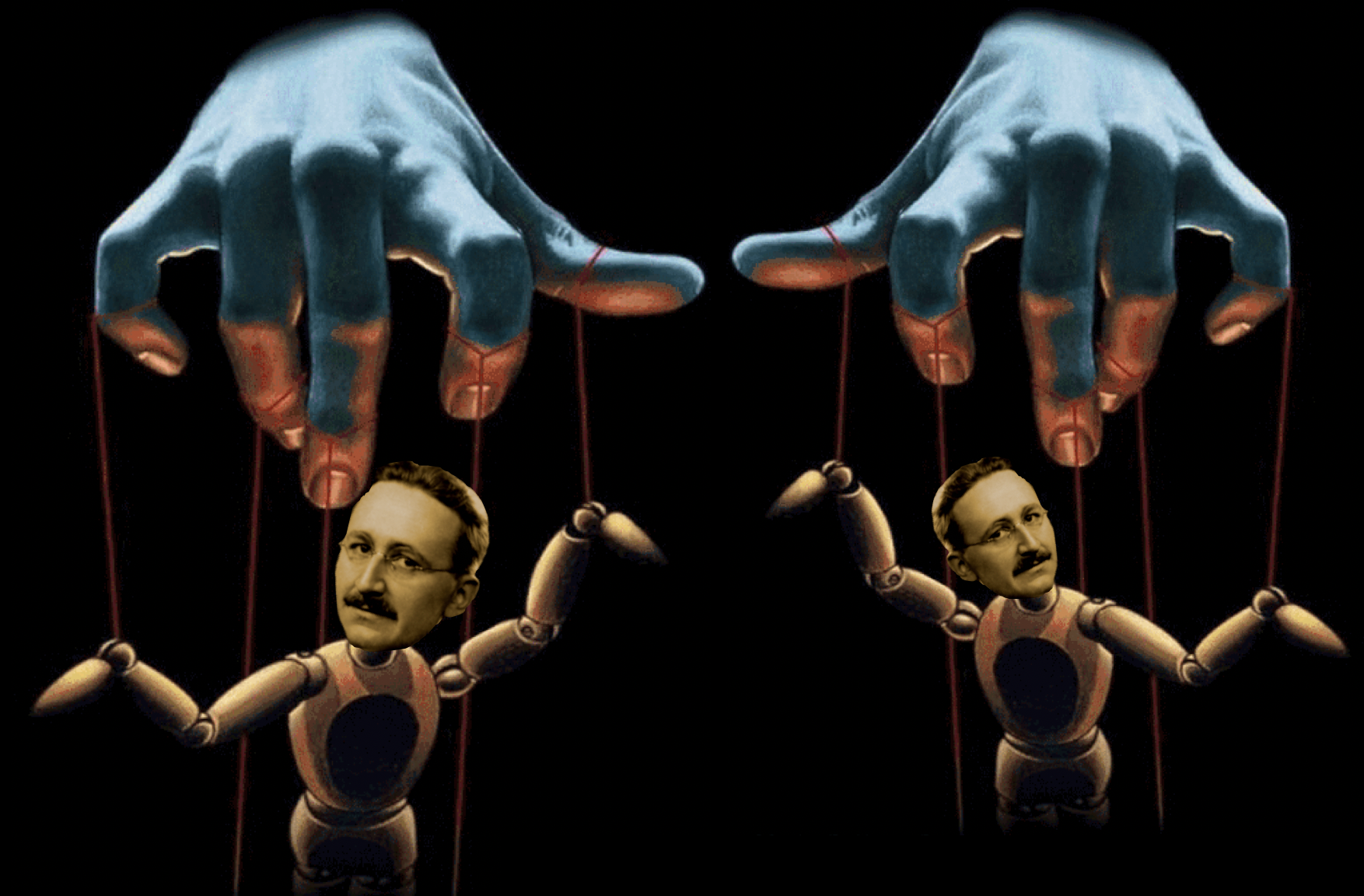

Democracy and despotism in a digital age.

Hayek’s Broken Promise

“Balanced” trade hasn’t worked out so well.

It is a tragedy that Friedrich Hayek’s excesses, invested with the authority of his (deserved) reputation, became the unexamined default for right-of-center economic thinking in America.

The resulting orthodoxy too often combines a Panglossian insistence on defending market outcomes regardless of their quality with a reflexive belief that policy intervention can only be distortive for the worse.

But when it comes to international trade’s effect on the American economy, a knowing assertion that nothing should be done, followed by yet another “analysis” working backward to an argument that nothing needs doing, will no longer do.

Hayek’s Faith

In his 1960 essay, “Why I Am Not a Conservative,” Hayek placed a falsifiable claim at the heart of his philosophy. It has proved false.

Conservatives, he began, “lack the faith in the spontaneous forces of adjustment which makes the [classical] liberal accept changes without apprehension, even though he does not know how the necessary adaptations will be brought about. It is, indeed, part of the liberal attitude to assume that, especially in the economic field, the self-regulating forces of the market will somehow bring about the required adjustments to new conditions, although no one can foretell how they will do this in a particular instance.”

Hayek’s honesty is admirable.

He “does not know” how adaption will occur. He “assume[s]” that “self-regulating forces” will “somehow” perform their critical functions. And he provides a testable example: “There is perhaps no single factor contributing so much to people’s frequent reluctance to let the market work,” he continued, “as their inability to conceive how some necessary balance, between demand and supply, between exports and imports, or the like, will be brought about without deliberate control.”

Balance between exports and imports—an interesting example. It is interesting partly for Hayek’s assertion that some balance between exports and imports is in fact necessary, a view not often ascribed to him. More importantly, it is interesting because he predicts that this balance will be achieved if we “let the market work.” Indeed, for Hayek, “faith” in the requisite spontaneous adjustment distinguishes and marks the superiority of his economic approach.

When an Era Ends

Hayek was describing the world around him. He wrote midway through two decades of a small and consistent trade surplus for the United States, which in 1969 came to rest at $91 million on almost $100 billion of exported and imported goods and services (an imbalance of less than 0.1%). No wonder faith in spontaneous and benevolent order was riding high. More generally, as economic liberalization marched in lockstep with rising prosperity through the middle of the 20th century, the bet on self-regulating forces must have seemed a safe one.

In hindsight, this faith in balance was the product of an era, not of a timeless and universal truth.

By the mid-1980s, U.S. trade deficits exceeded $100 billion annually (16% of trade); by the mid-2000s, $700 billion (22%). The argument for “free trade” shifted from faith in the miraculous materialization of balance to the claim that deficits did not matter, or were outright advantageous. Only rubes believed some balance necessary (as Hayek had himself).

If the mark of the Hayekian liberal is his confidence that required adjustments to new conditions will occur somehow, and that confidence proves misplaced; if the conservative’s reluctance to let the market work reflects his inability to conceive how necessary balance will be brought about by some undetermined means, and that reluctance is vindicated; well, what then?

Hayek forswears description of concrete mechanisms whose failures in this case might be evaluated, the better to modify and strengthen his theory. He posits the beneficial outcome as inherent in the system.

If reality refutes the system, what remains?

Analysis or Enthusiasm?

Much remains.

Hayek is among the 20th century’s most important thinkers, not for the simplistic absolutisms celebrated by blogs and Twitter accounts bearing his name, but for the serious and sophisticated analyses he offered on subjects including the operation of markets, the role of prices, and the pitfalls—economic, social, and political—of allocating resources by central diktat. Policymakers can apply those insights to real-world problems, identifying both situations where intervention by government is unwise and also those where it might be necessary.

In “Why I Am Not a Conservative,” he went too far. The telltale sign is his acknowledgment that his enthusiasm for market forces was outpacing his ability to describe them analytically. Analysts have been too quick to accept his overconfidence uncritically, and without acknowledging the assumptions they make in doing so.

An illustration of this phenomenon is Nicholas Eberstadt’s fine essay in the most recent issue of the Claremont Review of Books, which discusses in part my 2018 book, The Once and Future Worker.

I take Eberstadt as an example not because he is an easy mark but because, to the contrary, he is a political economist who brings a uniquely nuanced and thoughtful approach to the critical question of why so many Americans have been left behind by their nation’s economy. The essay brims with insight and he emphasizes a number of important themes that I too often overlook.

All of which makes his dogmatic deference to markets more remarkable—and representative of the posture typically adopted on the Right today.

Eberstadt takes issue with my “misguided notions about managing trade to revitalize employment,” the “all-too-predictable impact of [which] would be a poorer America—and one with less demand for work thrown into the bargain too.”

Why? Eberstadt doesn’t say. Which misguided policies? Eberstadt never describes one.

He offers nothing to support his criticism, only a conclusory dismissal that, “more generally, … the very best state-directed trade policy for the U.S. economy and the American worker would be one that never gets off the drawing board.”

In lieu of an argument, Eberstadt proceeds through thin rationalizations for our woeful status quo:

First, he says that “structural transformation” accompanying modern economic development makes the declining role of manufacturing employment inevitable.

Second, he suggests that service jobs are just as good as manufacturing jobs.

Third, he claims that with less foreign investment we might not have Nissan and Volkswagen manufacturing States-side.

All three are incorrect on their own terms; none provides evidence that managing trade is misguided per se, reduces jobs, or should never get off the drawing board.

“Structural Transformation”

Of course, economic development does lead to a decline in manufacturing jobs as a share of employment. From 1970 to 2000, that share fell from 26% to 14%.

But the level of employment is another matter. In both 1970 and 2000, 17 million Americans worked in manufacturing. From 2000 to 2012, as the share fell from 14% to 10%, 5 million manufacturing jobs disappeared.

An economy undergoing structural transformation can become more services-intensive while maintaining a robust manufacturing sector, with each job in the latter category helping to support many in the former. What does not work, and is by no means preordained, is an economy in which the service sector’s rise is accompanied by a manufacturing collapse: we cannot all cut each other’s hair.

The excuse of “structural transformation” is doubly inappropriate when the topic of concern is imbalanced trade. The issue is not that Americans ceased demanding ever-more manufactured goods, but rather that their voracious appetites are being met by workers overseas instead of creating new demand for domestic production.

Both the American trade deficit in goods and surplus in services are reminders that our “structural transformation” has occurred much faster in the labor market than would be necessary (or even possible) if the domestic supply of goods and services sought alignment with domestic demand. In a world where work done in America is dictated by what Americans wanted to buy, there would be much greater need for American manufacturing workers and less of a need for financial-services providers.

The U.S. market for investment banking services isn’t big enough for our MBAs, and our manufacturers don’t produce enough electronics. Perhaps investment bankers should apply their talents toward building productive new manufacturing enterprises. Some might even call this a spontaneous force of adjustment.

Those who dismiss the effects of trade as a consequence of structural transformation have their causality backward: trade has enabled and accelerated structural transformation.

But does this transformation matter?

Service Jobs ≠ Manufacturing Jobs

Eberstadt second defense is that “on a mean hourly basis, U.S. service sector jobs actually pay slightly better than manufacturing work.”

This is unpersuasive.

Taking the mean across all jobs allows high-paying ones at the service sector’s top end to skew the depiction of the labor market that the typical manufacturing worker might actually access. If we look instead at the mean for production and nonsupervisory workers, we find that the average hourly wage for “goods-producing” sectors is $1.50 higher than for “services-producing” sectors. Dig deeper, and the $22.14 per hour wage in manufacturing lags behind $33.85 in the information sector and $27.78 in professional and business services, but runs well ahead of $16.61 in retail and $14.50 in leisure and hospitality.

The real question here is which jobs are the likely substitutes for ones in manufacturing?

In The Once and Future Worker, I provide the concrete example of Pittsburgh, “sometimes cited as a poster child for postindustrial transformation from heavy industry to health care.

From 1990 to 2016, the Pittsburgh area lost forty-six thousand manufacturing jobs while gaining sixty-seven thousand health care and social assistance jobs. But while ‘production’ jobs in the area paid a median hourly wage of $18 in 2016, in line with the area’s median for all occupations, ‘health care support workers’ earn $14 and ‘personal care and service workers’ earn $11.” Comparing overall averages makes sense only if the former manufacturing worker has as good a chance as anyone of finding his next job as a surgeon.

Nor should we accept current manufacturing wages, reflective of years of underinvestment and low productivity growth, as somehow inevitable. In countries like Germany and Switzerland, which make robust and globally competitive manufacturing sectors a priority, compensation is 30 to 60 percent higher.

Less Foreign Investment?

Finally, Eberstadt worries that an effort to rebalance trade would mean less foreign investment in the American economy.

This is, mathematically speaking, correct.

A trade deficit does not leave the importing party with a free lunch. A “trade” must still occur, and if we do not send our goods and services abroad in exchange for the ones we receive, we must instead send our assets—U.S. Treasury bonds (IOUs to pay later for the things consumed now), corporate debt and equity (a claim on the future profits of our businesses), real estate. When foreigners buy these things, they are “investing” in America.

We should not celebrate such a mortgaging of our future.

Eberstadt highlights a form of investment that does seem desirable—the “foreign direct investment” (FDI) that occurs when foreign auto companies build manufacturing plants in America. Such investment is a rounding error. In 2018, of $287 billion in FDI, less than one percent went toward the establishment or expansion of manufacturing facilities. Almost 97 percent went toward stock purchases.

Recall, incidentally, what spurred Japanese car manufacturing to American shores in the first place: President Ronald Reagan’s “state-directed trade policy.” As the New York Times explained the 1985 opening of Nissan’s plant in Smyrna, Tennessee, “Instead of flooding America with cars made at home, and risking new protectionist measures, the Japanese are ‘going native’—opening up American plants.”

The China Challenge

I have not yet mentioned China.

That’s because Eberstadt, like many others, refuses to grapple with its implications. Instead, he calls China a “card” that I “play,” and reduces China’s misbehavior to intellectual property theft, which is already illegal and so requires no new policy, “just an elected government with the courage to confront Beijing about its criminal behavior.”

How one “confronts Beijing” without “state-directed trade policy” is unclear.

Why we should care about China’s behavior, if the lost manufacturing jobs were inevitable, new services jobs are just as good, and trade-deficit-driven “investment” is downright desirable, he does not say.

And yet, he is open to “systematically excluding China from our international supply chains” on national security grounds—a proposed disruption far beyond anything I have ever suggested.

China is not a card for playing. It demonstrates a fundamental property of our global economy, which is that countries pursue strategic economic policies that affect markets beyond their borders. China is an especially large country.

But Germany and Japan are quite large as well—their combined manufacturing output is similar to America’s. And, as Eberstadt notes, their policies seek to distort economic outcomes too.

The Hayekian enthusiasm for self-regulating forces and spontaneous adjustment, even stipulating their efficacy in a free market, does not translate to the modern international system. Perhaps it is a defense of Hayek to say that he was not contemplating how nations now behave. That would still leave his conclusions inapplicable.

“Should our moral beliefs really prove to be dependent on factual assumptions shown to be incorrect,” Hayek observed in his essay, “it would be hardly moral to defend them by refusing to acknowledge facts.”

Any particular proposal to address the challenges of a malfunctioning market deserves scrutiny and criticism, but each must be met on the merits.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Part I: Unfettered reason cannot conserve anything.

One dose will erase your whole political mind.