How our political leaders lost our trust…and how we enabled it.

A New Birth of Leadership

Recovering statesmanship in an age of mediocrity.

An earlier version of this essay was presented on July 28, 2023 at the Colloquium on the Modern View of Leadership in Washington, D.C.

The competent leader of men cares little for the interior niceties of other people’s characters: he cares much—everything for the external uses to which they may be put…. Men are as clay in the hands of the consummate leader.

Such are the words of Woodrow Wilson in his pathbreaking 1890 lecture and essay, “Leaders of Men.” As a thoroughgoing Progressive, Wilson propagated an idealism in a new kind of “leader” in society who possessed both empathy and vision. In his view, the modern leader must know the people’s needs and then, like an Old Testament prophet, cast a vision for a better future in line with the Progressive view of History, which propels man’s political and social advancement.

The impact of Wilson’s teachings cannot be overstated. One can hardly imagine any book, workshop, or seminar on modern leadership today that does not emphasize these qualities, among others. Literally thousands of publications promulgate an almost infinite array of leadership laws, rules, values, guidelines, and platitudes. In one contemporary college textbook, students even learn the importance of avoiding microaggressions as key to successful leadership. Forbes has reported that, overall, the global “leadership development” industry has raked in $366 billion.

To understand the abiding influence of Wilson’s teaching on leadership, we must first understand why it proved so revolutionary in the first place. Why was Wilson’s understanding of leadership—which was folded into a larger critique of the entire constitutional system crafted by the American Founders—so novel?

The Founders and Leadership

Leadership as a term is not new, of course, but its modern celebration as an unqualified good is peculiar.

Though often viewed today as “leaders,” the American Founders did not refer to themselves in that way. In fact, they looked askance on the concept of the “leader” and “leadership” in the political realm. Interestingly, the words “leader” and “leaders” appear almost nowhere in the major writings of the Founding period. As Charles R. Kesler has noted in several places, The Federalist mentions “leader” and “leaders” only 14 times, all but twice pejoratively. (The two approving mentions relate to war scenarios, praising “the leaders of the revolution” and the “patriotic leaders” of the Revolutionary War.) Publius generally associated leaders with fostering factions, practicing demagoguery, and modeling vice.

The Founders’ government eschews the need for popular leadership, which may capitalize on the people’s passions and lead them astray from their better, more permanent interests. Moreover, such leadership immediately raises a challenge to what Abraham Lincoln referred to as the “sheet anchor” of American republicanism—human equality—as it labels some as “leaders” and others as “followers.” (A more nuanced, and true, teaching on equality by Lincoln is provided below.)

As mass democracies and political parties grew in the 19th and 20th centuries, the call for leaders emerged with greater alacrity. Mussolini styled himself il Duce and in Nazi Germany, Hitler as de Fuehrer—both titles translating directly as “the leader.” These men understood the power of leadership, and they serve as glaring examples of the kind of “leader” the American Founders greatly feared.

Though Woodrow Wilson’s impulses kept him anchored to the people, emphasizing the importance of gaining what he called “sympathetic insight” into their needs, the Wilsonian leader could nevertheless in theory use rhetoric to rouse people to see their common struggles and move them forward to a better, brighter day. It was in fact through Wilson’s influence that the leadership virus was firmly released into the American public, taking little time to infiltrate almost all sectors of American society.

In contemporary politics, American leaders of various political persuasions clearly demonstrate the concerns that the Founders held, especially given their permanent view of human nature, which Wilson and other Progressives deemed archaic. The Founders thought there were permanent standards found in nature—the “laws of nature and of nature’s God”—which necessitated a permanent form of government. By contrast, the Progressives saw not nature but History as the guide for assessing the evolving standards of moral and political life. Thus, the Wilsonian leader proves necessary to unite the disparate strands of American politics and lead the nation forward given the dictates of History.

America has avoided true tyranny in large part because of the prevailing—though attenuating—strength of the American constitutional system and the people’s veneration of its governing documents. Yet, one questions just how long the Founders’ constitutional system can endure given current leaders who, at best, see it as an antiquated stumbling block to their political desires or, at worst, as a system to be overcome by their own towering genius. The tyrannical leader—the one from “the family of the lion, or the tribe of the eagle” as Lincoln put it in his Lyceum Address—may yet spring from the Wilsonian model.

A Pseudo Aristocracy?

One finds an alternative to the contemporary approach to producing “leaders” in assembly line fashion in the writing of Thomas Jefferson. Writing in 1813 to his former rival John Adams, Jefferson identified the success of the future American regime as tethered to the emergence not of an artificial aristocracy based on “wealth and birth” but of a natural aristocracy based on “virtue and talents.” For Jefferson, “The artificial aristocracy is a mischievous ingredient in government, and provision should be made to prevent its ascendancy…. I think the best remedy is…to leave to the citizens the free election and separation of the aristoi from the pseudo-aristoi, of the wheat from the chaff.”

Inherent in Jefferson’s promotion of a natural aristoi is a teaching about equality that is often misunderstood. That is, all men are created equal and deserving of the dignity that equal natural rights bestow; however, at the same time, they are unequal in their individual virtue and talent. In this respect, man can be both equal and unequal. In his debates with Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln noted that the Founders “did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects.” In fact, they “defined with tolerable distinctness, in what respects they did consider all men created equal…equal in ‘certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’”

Jefferson saw classical education as the means through which men of virtue and talent would distinguish themselves in society. One finds a blueprint for propagating this kind of education in Jefferson’s plans for the University of Virginia. Commenting on these plans, Harry V. Jaffa stated that it “would assist the people in a democracy to recognize their true representatives, and defeat the plots of the scoundrels posing as aristocrats.”

Yet, and ironically, the modern proliferation of leadership programs and degrees—combined with the Woke regime and the desire by many to elevate individuals to positions based almost exclusively, or even solely, on their minority status—has engendered something like a contemporary “artificial aristocracy.” This artificial aristocracy is not based so much on wealth or birth but perceived leadership credentials, degrees, race, gender, and sexual orientation. If you have a leadership degree from a university, then voila!—you must be prepared to lead. Combine that with a particularly exotic minority status and you are likely to be elevated to even more prestigious leadership roles.

This is a kind of leadership intersectionality. Such individuals may have virtue, prudence, courage, ambition, and justice in their souls, but their selection may not be contingent on demonstrating such qualities. A review of advertisements for open executive positions at universities and Fortune 500 corporations (as just two prominent examples) clearly highlights that this is the new type of “leader” they wish to bring on board.

With this in mind, can a natural aristocracy—a true leadership class—exist in 21st century America?

Back to the Future

The development of our leadership-obsessed culture has been largely unsuccessful in producing a natural aristoi of any note in the political arena. It could even be argued that the more we attempt to produce “leaders,” the fewer individuals of leading distinction exist. If one examines the major party candidates for president over the past 100 years, it is questionable if any would qualify for a chapter in an updated version of Plutarch’s Lives.

Yet, such clarity on our present discontents can help in sorting through the brush of modern leadership theory to identify what the Founders themselves understood as necessary for true leaders in the making.

The Founding generation embraced an archetype in the “statesman,” that individual who—going back to at least Aristotle—combined a commitment to principles with the prudence to implement them in changing circumstances. As Clifford Humphrey has argued at The American Mind, “The character of any regime is provided by its statesmen, its leadership class, since they embody and maintain the prevailing standard of excellence toward which the rest of the regime is oriented.” It is notable that the title of “statesman”—which suggests moral seriousness—is so infrequently bestowed today, while “leader” is peddled so frequently and so thoughtlessly that it is increasingly emptied of enduring meaning.

One can see how statesmanship stands in contrast to modern leadership, which promotes sympathy with the people and articulating a vision of the future. Of course, the morally right action in any circumstance may require standing against popular views, a position that proves difficult when one’s touchstone is the people’s shifting opinions or attempting to divine an unknown and unpredictable future.

To dissuade citizens from their overwhelmingly positive view of “leadership”—a word that now manages to simultaneously be both morally barren yet culturally ubiquitous—proves daunting. There is no question that dislodging the term “leadership” and replacing it with “statesmanship” will require playing the long game. It will require statesman-like prudence, not to mention patience. Yet, one should not despair, for, as William F. Buckley once put it, “the wells of regeneration are infinitely deep.”

Two steps can initially be taken.

First, we should teach a concept of leadership that will pave the way for statesmanship. One finds a roadmap for the education of such a leadership class in the writings of George Mason. In 1776, Mason drafted Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, whose 15th article reads as follows:

That no free Government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue, and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.

The country is in desperate need of individuals who possess such fundamental qualities, along with a rich understanding of the “principles of the revolution,” as The Federalist puts it. From here, we must engage in the hard work of cultivating—in the individual soul, in the home, in the schools, in the churches—the qualities Mason listed that prove necessary for the education of statesmen and the perpetuation of republican government.

Second, those natural aristoi who could succeed in largely any endeavor must understand why their virtue and talents should be marshaled in the service of their country. This will require, in part, making America respectable and defensible in the eyes of rising generations. That will prove no easy task.

Though Glenn Ellmers has convincingly argued that there is much work being done to deconstruct America, future American statesmen must understand why the country is good and worth preserving. They must understand why they may even need one day to sacrifice their “sacred honor” to defend it. Virtually all K-12 schools and universities in America have either proven inept at such a task or have wholly rejected it. Moving forward, the education of such an informed patriotism will increasingly need to be facilitated by what Edmund Burke called the “little platoons” of civil society such as the family, church, and civic associations. Compared to almost all K-12 schools and universities, such entities are more immune from partisan political forces, fears of political correctness, and, of course, contemporary leadership teaching.

The time has come for citizens to begin the important work of recovering these ideals and teaching them to the next generation, a generation who—through their conduct and example—can ensure the blessings of liberty for themselves, their families, their community, and their nation. It is through this noble cause that we may achieve a new birth of leadership that, through a process of sanctification, can mature into true statesmanship.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Postcolonialism rivals Jacobinism and Bolshevism in its systematic destruction of civil society.

Don't lose hope!

Is California turning on its Jews?

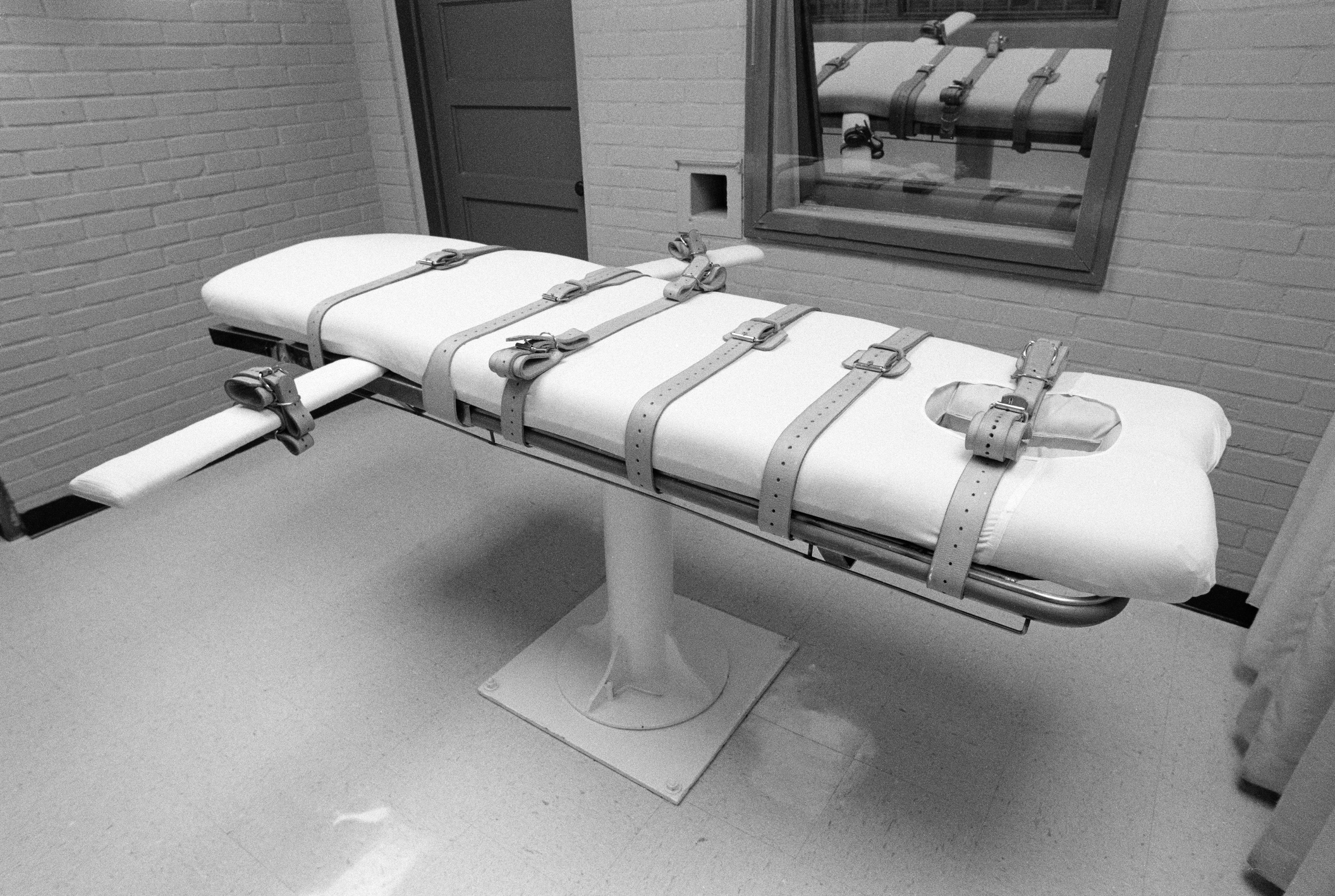

The new direction in anti-death penalty activism.

Delegitimization of the justice system is a key step toward progressive domination.