Elites dissemble, but people are hungry for a new, fully free university.

Yesterday the Faculty Lounge—Today the World

The cradle of multiculturalism has been sprung.

“A seminary of anti-Americanism” is Ryan Williams’ striking synopsis of American education. This nicely captures the frequency with which the contemporary campus raises a middle digit to love of country. The orthodoxies of the academy today are that the United States was built on a foundation of slavery, genocide, and myriad forms of oppression. Moreover, they contend, the nation’s founders were hypocrites of various stripes, slaveholding being only the foremost of their transgressions. American institutions of education today teach that the founders left us with a nation designed to preserve the privileges of wealthy white males at the expense of everyone else.

These premises are put forward in an attitude of superior wisdom. The cosmopolitanism of the professoriate (and of many school teachers as well) holds that their truths are self-evident, and only the willfully ignorant could believe otherwise. Americans are supposed to simply know that behind the pieties of freedom and justice for all, the United States is and always has been an enterprise of ruthless exploitation in which the rich and powerful have extracted what they pleased from the weak and submissive.

This amounts to the progressive left’s credo, now established as something approaching the baseline understanding of American history, economics, and politics. All else is detail. We can have scholarly disagreements about the exact balance of racism, sexism, militarism, capitalism, and so on, but it is generally now out of bounds to seriously consider that America might be understood to be about the pursuit of human equality, the love of liberty, or the formation of a unified nation. Still further out of bounds is the concept that America, despite its ethnic and religious variety, possesses a vibrant common culture.

Multiculturalist Education is a Political Problem

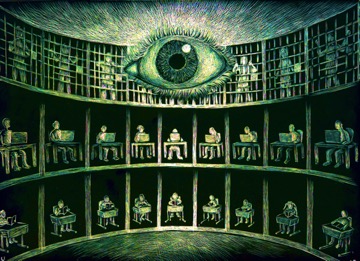

Essential to the higher education establishment’s governmental funding stream, and the electoral politics behind it, is the establishment’s ability to deflect the criticism that it mainly teaches outright disdain for America.

I have spent many years revealing the true state of higher education. In a previous essay, I responded to the objections and obfuscations that defenders of the system typically make when confronted with accurate characterizations of its multiculturalist status quo. But Americans as a whole have not yet been persuaded that higher education is thoroughly turned against the general welfare of the country. Academic doubletalk, institutional prestige, the sturdy respectability of the sciences, the lure of gainful employment via recognized credentials, and fondness for alma mater have all blurred away a widespread recognition of the obvious: colleges and universities are now engines of alienation for students and large-scale propagandists for post-national sentiment.

This is a political problem.

American higher education as we know it today is largely run on funding that comes directly (grants) or indirectly (student loans) from the federal government. The left’s dominance of higher education is possible because Democrats are eager to subsidize it and Republicans are afraid to say no, or to involve themselves in education as anything more than a jobs-preparation utility.

Democrats intervene and Republicans stand pat, reluctant to counteract or undo liberal and now progressive interventions because they believe intervention of any sort is off limits. Intervening, after all, would concede that the government has a legitimate role in shaping higher education, and it might also create new powers of government that the left would sooner or later abuse. These considerations amount to self-imposed rules that Republican office holders play by. Few stop to ask how and why those rules exist or when they might lose their applicability.

It might, for instance, have been a good idea once upon a time to keep the federal government out of higher education, but at least since 1944 (the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act—the G.I. Bill) the federal government has played a large and ever-expanding role in funding and steering higher education. Sitting on the sidelines in petulance or apathy does nothing to change that. It merely ensures that the left has free sway.

Republicans need to understand a cardinal principle of republican government: the purpose of education is to train the next generation of citizens on behalf of the public welfare. There are other secondary purposes, such as credentialing the workforce, but fostering citizenship is the fundamental reason for state involvement with the institution. It is the job of the federal government to ensure that the states and private sector fulfill their responsibilities to sustain an educated public capable of the task of self-government.

When colleges teach multiculturalism, they teach students to disdain America instead.

The Consequences

Generally, colleges do understand themselves to be teaching the next generation of American citizens but they think American citizens are best conceived of (and therefore taught) as “global citizens.” Though that term is immensely popular on campus these days, it is intentionally vague. It belongs in a word cloud with sustainability, diversity, and a host of other terms that evoke a world of international norms that transcend national identities. It is a borderless world, but not lacking in distinct traditions.

Global citizens, for instance, are tolerant of Islam and most other religions with the conspicuous exception of Christianity. The hostility of multiculturalism to traditional Christianity might seem at first puzzling, since Christianity is itself a cosmopolitan, egalitarian religion. But Christianity is also, of course, the predominant religion of America and the West. And because multiculturalism is essentially an attack on American identity, Christianity is seen as an obstacle, worthy of neglect and derision the academy gives other American institutions.

The consequences of our multiculturalist educational system for American political and cultural life are direct and profound. Such multiculturalism authorizes a cultural and political elite that rules by means of its triumphant versatility in negotiating all the sensitivities of a multicultural society. Its elite status is reaffirmed each time it can identify a supposed transgressor.

In the political realm, Brett Kavanaugh was a transgressor par excellence: a white, male Christian raised in affluence and educated at prestigious schools who stood accused of sexual assault. Those who arose in high dudgeon against Kavanaugh had no need of evidence because in these realms accusation is self-validating.

The Kavanaugh hearings took many ordinary Americans by surprise. They lacked previous experience with trial by accusation. But no one familiar with Title IX cases on campus or academic feminism was caught off guard. I wrote of it at the time under the title “Accusation Studies,” and the incident serves as a key link between the multiculturalism of the academy and multiculturalism as it reverberates through America as a whole. Within the academy, accusations are now deployed not out of an attempt to expose malefactors or advance justice, but rather to heap opprobrium on supposed enemies. Shredding reputations—“canceling” people—is the goal, not finding the truth.

This isn’t incidental to multiculturalism; it is the basic rule of the game. Seeking justice or truth would imply the external existence of standards, and an epistemology that allows for commonly understood ideas of what counts as evidence. In the multicultural universe, justice vanishes in favor of “social justice” and evidence becomes whatever one experiences as “one’s truth.” Professor Christine Blasey Ford exemplified the “my truth” approach to social justice, and the “I believe all women” tag line voiced in the underlying epistemology. Why believe anything in particular? One possibility is to believe those whose “social position” most closely coincides with your political interest.

Such views are profoundly incoherent. Incoherence, however, has its cheerleaders in the academy: the proponents of various forms of postmodernism, who hold that reality itself is fragmentary and discontinuous. In their view, imposing a coherent “narrative” atop the buzzing chaos of everyday life is an act perpetrated by power-hungry patriarchs and their intellectual adjutants. The honest response to the world is to embrace its disjointedness and rejoin the pieces ad hoc as part of the new social justice.

This is perhaps no more than another way to describe multiculturalism at the moment when it has drunk too deep from its own well at the faculty club. But what was once said almost exclusively at the faculty club is now integrated into mainstream political practice throughout the nation. The only difference is most multiculturalists couldn’t carry the conversation as far. They would simply get indignant, and say something intemperate such as “I am Spartacus.”

A Disease of Republican Virtue

The link to political drama is one of the ropes that ties higher education to Williams’ larger thesis that multiculturalism poses an “existential threat to the American political order” and to “Western civilization as a whole.” Those are large claims indeed, and one wants to avoid hyperventilation. Something can be a threat, even a dire threat, without raising alarms so loud. Are “the common good and a life of civil peace” at risk? I am reminded of Tacitus excoriating his fellow Romans in Germania about their loss of civic virtues. “No one in Germany finds vice amusing, or calls it ‘up-to-date’ to seduce and be seduced.” He warns that the German tribes’ love of freedom makes them a great potential adversary to Rome. On this, of course, Tacitus was eventually proved right.

Take it from a quondam professor of anthropology: the idea that America is really a multicultural society is absurd. One can find such places, in some nations in sub-Saharan Africa, in New Guinea, in India, and a few other locations. Multicultural societies in the real world are the result of long-isolated enclave populations, mass immigration, or imprudently drawn colonial borders. The results are political instability and typically suppression of minorities. I know of no instances in which a relatively happy and stable multicultural dispensation has emerged. The United States can be grateful that assimilation to republican ideals has so far prevented our becoming multicultural in a literal sense. We have pressured and sometimes bullied immigrant populations into assimilating, but the general rule has been that immigrants have been eager to get on the train. It isn’t pre-ordained that immigration will always fall into such a benign pattern for us. Attempting to assimilate immigrants is bound to be a great deal more difficult when our cultural and political elites treat the ideal of assimilation as an offense against cultural authenticity.

Multiculturalism is really a form of decadence, a disease afflicting the norms of republican virtue, by an extreme extension of a few of those norms at the expense of the rest: a social hypertrophy. In this case, the republican ideal of tolerance of differences has grown into the hypertrophied form of hatred for superintending ideals of shared identity and the common good. Such inflated notions of cultural division can be played for partisan advantage, at least in the short term, but they permit no sustained loyalty to the larger enterprise of sustaining a free and self-governing republic. The Germans may not be at our border, but the world is a dangerous place, and we don’t lack for enemies who are unhampered by multiculturalist illusions. Claims of equity, inclusion, and diversity are empty words to those enemies, who can only admire their good fortune that we are so intent on cultural disarmament.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The longing to universalize the college lifestyle has turned academia into a church of hypocrisy.

Today’s power struggle is the stuff revolutions are made of.

Our universities have replaced justice with despotism.

The era of wisdom on campus is over.

Our academic institutions are rotten to the core. It’s time to replace them.