Elites dissemble, but people are hungry for a new, fully free university.

Remake Higher Ed—Before it Unmakes America

Our academic institutions are rotten to the core. It’s time to replace them.

The problem of American higher education is no longer the proper subject of fusty jeremiads or partisan clickbait. It now raises an irrepressible regime-level question: and whoever addresses it successfully will re-form American government and establish corresponding ways of life over the next century.

The problem of higher education in our era is now institutional. It can only be finally resolved by re-forming and remaking our educational institutions—or by founding and building anew. As Peter Berkowitz recently suggested, “the restoration of liberal education—either through reclaiming it on campuses from the illiberal forces that dominate there or by creating outside of established colleges and universities supplemental programs and alternative institutions—is crucial to healing our frayed republic.”

Our Form of Government Is In Question

Whatever one thinks of the reasons Patrick Deneen gives in his book Why Liberalism Failed, concerned citizens of the western democracies increasingly agree that “liberalism,” at least considered as the governing political ideology post-Second World War, is failing. Younger conservative and religious intellectuals and social justice warriors alike consider “illiberal” options instead. This increasing recognition that our ruling class’s understanding of politics is inadequate to resolve the political strife of our era—and may instead be causing it—is resulting in a corresponding dissatisfaction with the very form or structure of our political system.

What unites the young in dissatisfaction is a clear-eyed understanding of the failure of previously settled ideological assumptions on both Right and Left to meet the growing challenges of lived reality. The basis for their dissatisfaction is not merely ideological but arises in large part from grappling with their lived reality of our current societal challenges. Despite the fact that we are wealthy and technologically advanced in comparison to the rest of the world, virtually all of our major institutions, civic and otherwise, have lost or are quickly losing the trust of the public. This dissatisfaction runs so deep, and the responses of our current leaders on the Right and Left to these challenges are so thin, that the very kind of government currently established in the West is increasingly in question.

So it is that aging baby boomers running our unpopular and unsuccessful civic and social institutions struggle to understand the discontent swirling around them, and bright young people on the Right and the Left speak of regime change. Surveying the current state of American politics, they fault the principles of American government as they understand them, quietly but firmly consider sweeping measures for change, and rally around alternative accounts and forms of government.

On the Left, progressive liberalism has metastasized into a multiculturalist vision of identity politics condemning the “systemic” oppression of the American political structure. This vision is increasingly enforced by political correctness, which is now actively remaking our systems of justice. Changes to the Constitution are frequently and openly discussed by mainstream figures, and the Democratic Socialists of America are quickly gaining political ground.

On the Right, young intellectuals express distaste for reigning libertarian-leaning understandings of liberalism, and the very notion of individual rights. They decry the Right in previous decades for its fecklessness, and increasingly discuss the need to wield governmental power for the sake of the common good. Those who are Christian look to older notions of religious political power.

Since the idea of constitutional change is anathema on the Right, and most of its institutional leaders refuse to rethink the intellectual framework of policy even in the wake of President Trump’s victory, discussions among the young about what ought to be done to save our dying Republic are pushed underground. This exacerbates an increasingly radical generational disjunction in thought that will soon lead to even more sudden and radical breaks in political practice than those that have erupted so far.

Rising young leaders are earnest when they discuss the depth of what must be changed, yet they’re often smug when it comes to the deficiency of our regime form, even if the cause of these deficiencies is in much dispute. They are united in the vague but deep conviction that governmental power of the Right needs to be used to re-form government itself, and to retake and shore up our civic institutions. What unites them when they look for more particular solutions, however, is not “privilege” but shared ignorance. They are largely unaware of older American principles and purposes and the available options that might otherwise be open to them in their effort to repair the failure of liberalism at home and abroad.

This state of affairs ought not be shocking. It is a direct effect of the conservative movement’s failure to retake our educational institutions. We have already passed the point at which a large part of the 330 million people living in America have little to no idea of the basic operation of the regime form in which they live, never mind its original philosophical underpinnings. But our educational system has also failed the potential leaders who could save America in the coming years.

Education Forms Government

We are naturally political beings, yet we are also naturally rational beings. It is natural for human beings to live in political communities, but governments don’t grow on trees. We form the political structures that form us. We do so according to our understanding of what we are and ought to become: according to what we understand of our own nature.

But education forms our habits of mind and what we think human beings are and ought to be, and thus education shapes the way in which we think about what sort of government we ought to make and maintain, or how to order the communities in which we live. Over the last century and a half, America shifted regime forms, moving from a predominantly Christian constitutional republic to a secular regulatory administrative state that is increasingly hostile to both the Western tradition’s religions and its understanding of natural justice. This change would have been impossible without the corresponding change in education that preceded it at every turn. American higher education has achieved much in terms of technical accomplishment since these changes began, but it has increasingly ignored and ultimately rejected the core principles, elements, and purposes of the education of the Founders that made these men, and hence America, great to begin with.

Charles Kesler summarized “the wisdom of the Founders’ view on education” thus: “without citizens, no republic; without republican education, no citizens.” As Peter Wood points out, “Republicans need to understand a cardinal principle of republican government: the purpose of education is to train the next generation of citizens on behalf of the public welfare. There are other secondary purposes, such as credentialing the workforce, but fostering citizenship is the fundamental reason for state involvement with the institution.” Our educational system today rejects the very notion of republican citizenship, and, as Wood suggests, it often does so by teaching the concept of “global citizenship”—a phrase that equivocates on the very meaning of citizenship, which implies membership in a given political community.

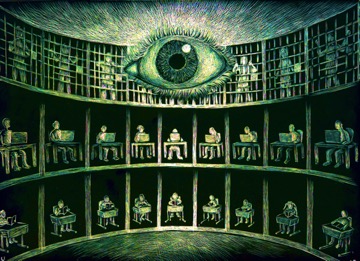

But, as Angelo Codevilla once wrote, “few in Washington or academe even know what the word ‘regime’ means.” Long since ceasing to provide “republican education,” our educational system fails to teach anyone what a “republic” is. This failure runs deep. As Patrick Deneen argues, our higher educational institutions used to believe that “a civilization must protect liberty through the cultivation of principles of Justice and Right.” At the heart of early American education were “classic and Christian texts” that informed American statesman and leaders from the time of the founding to modern figures such as the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. Such texts taught students “norms of justice, variously developed in the classical tradition based upon appeal to reason, or, in the Christian tradition, supplemented by appeals to faith but also fundamentally based in rational knowledge of the natural law.” These appeals to the standards of nature knowable by means of reason and faith were “understood to be the ultimate forms of limitation upon the tyrannical exercise of political power.” Having rejected this education, our institutions “are today in the forefront of advancing new principles of despotism.”

As modern education rejected the traditional classical and religious understanding of human nature, morality, and politics, it yet took on the role of religion in forming morality. “From the late nineteenth century onward,” Bill Allen argues, “American higher education assumed the role of moral arbiter previously performed by the church,” leading to the “new Salem” developing at colleges like Oberlin—each with its own “pursuit of devils and witches.” (In a recent essay for The American Mind, Joshua Mitchell ably describes the theological and political origins of this new woke religion.)

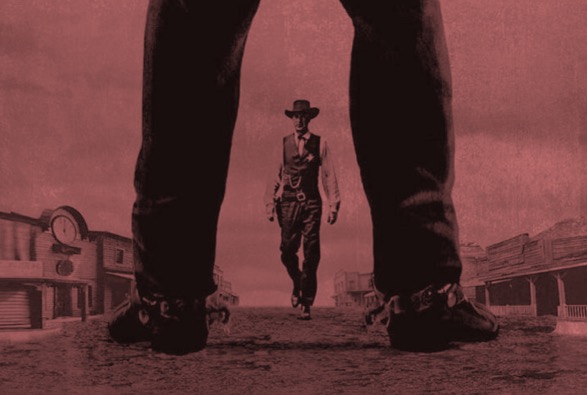

As Colleen Sheehan rightly says, the root of the cold civil war currently unfolding in America “is not, in its essence, about this or that policy; it is over what it means to be human and how we should live our lives.” Far exceeding the bounds of inherent, routine political disagreement about how best to secure the common good, today’s “disagreement could not be more fundamental. This is the stuff revolutions are made of.” This is why, as she boldly asserts, “it is High Noon at the American Academy.”

Sheehan is quite right that on one side the Left, and the vast majority of our educational institutions, “rejects the phenomenon of nature, including human nature and the idea of ahistorical rights and responsibilities.” Yet, on the other hand, it isn’t altogether clear how much the Right “wants to preserve the traditional American character and ethos, including the idea of a standard maxim grounded in human nature and equality, and the natural rights and duties derivative from it.” Now is the time to establish some clarity.

The Blindness of the Right

Nearly 70 years have passed since William F. Buckley launched the modern conservative movement by publishing God and Man at Yale, castigating the atheism and the flirtation with communism so prevalent at his alma mater. In the intervening years, conservatives have spent a lot of time yelling stop, and our colleges and universities have nonetheless worsened. For all the books decrying the failings of higher education, to this day most on the Right still send their dollars and their children to the same institutions they love to castigate in speech.

As Michael Anton pointed out in The Flight 93 Election, conservatives talk about our “disastrously awful educational system that churns out kids who don’t know anything;” but “if they are right about the importance of education to inculcate good character and to teach the fundamentals that have defined knowledge in the West for millennia…then they must believe—mustn’t they?—that we are headed off a cliff.” This is partly why it was puzzling that “conservative thought over the last decade at least” could be characterized by “the unwillingness even to entertain the possibility that America and the West are on a trajectory toward something very bad.”

This contradiction is resolved, however, when one considers that the Right, no less than the Left, has been predominantly composed of leaders educated in the same desiccated system it decries. If it is not now clear to right-leaning leaders and donors that our educational institutions seek to unmake America—not only by teaching it should be despised and deconstructed, but by transforming its political, legal, cultural, and familial structures into something else entirely—they are willfully blind and will deserve the tyrannical consequences of inaction.

Contrary to what donors might prefer to believe, the failure of our educational system is not merely procedural, or a matter of flawed means, but structural, or a matter of purposeful ends. As Wood says, “when colleges teach multiculturalism, they teach students to disdain America.”

Looking at their form and content in terms of their often explicit goals, our educational institutions are not badly designed; they are ordered to achieve precisely what they are systematically accomplishing: the rejection of the original American understanding of natural rights, equality, justice, and deliberative, representative government; the purposeful Balkanization of America into racial and other identity groups; the destruction of the traditional human family; and, ultimately, the despotic imposition of a radical vision of global transhumanism that reorders society.

In 2001, historian Charles Dew wrote a book entitled Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War. In their reckless denigration of American principles and purpose and encouragement of a new form of segregation, our higher educational institutions have become modern day Apostles of Disunion. In a sense, our educational institutions are now worse than the secession commissioners in that they teach the whole nation, not just a part. As Claremont Institute President Ryan Williams recently stated, “multiculturalism has transformed the American educational system from a vehicle for the cultivation of an informed and responsible citizenry and the assimilation of immigrants into a seminary of anti-Americanism.”

This is, in Wood’s words, “a political problem,” and the solution in large part will be found only by political action in opposition to the higher education establishment. The problem will therefore not be sufficiently addressed, as Frederick Hess warns, by “well-meaning efforts to protect free speech, establish speaker series to bring diverse voices to campus, create campus outposts of heterodox thought, and foster civil debate.” Such efforts are, as Hess says, “primarily defensive actions” which “are helpful but ultimately insufficient.” It is worth noting that William F. Buckley’s subtitle to God and Man at Yaleback in 1951 was “the Superstitions of Academic Freedom.” While such defensive actions have been increasingly necessary for decades, our current Republican leaders are so worthless they give only lip service them, as Rachelle Peterson rightly laments.

The Way Forward

In the coming weeks, The American Mind will further explore the cause of higher education’s failure to produce the right kind of civically-minded leaders, the core problem of the modern curriculum, and what it will take to re-establish the kind of educational system our nation so desperately needs.

We must remember that, as Berkowitz advises, education “is where culture warriors…should concentrate their fire. It is in the domain of education—for all ages and in America particularly at the state and local levels—that liberal democracies, consistent with their foundational commitment to securing liberty by limiting government, can most effectively promote public morality.” But if we and others are to successfully do so, and so save our decaying Republic, the conservative movement and its donors are increasingly going to have to put their time, money, and action where our mouths have been for the last 70 years.

If we do not, we will continue our slide into irrelevance, moving from what little influence we have on today’s tidal political changes—to having none at all.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The cradle of multiculturalism has been sprung.

The longing to universalize the college lifestyle has turned academia into a church of hypocrisy.

Today’s power struggle is the stuff revolutions are made of.

Our universities have replaced justice with despotism.

The era of wisdom on campus is over.