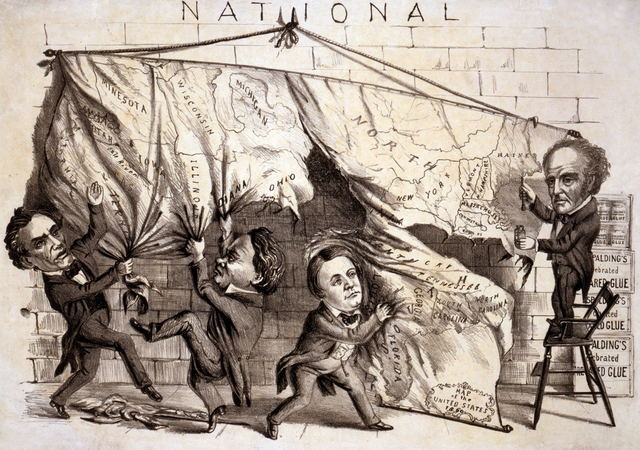

To win, the Right must distinguish anti-Americanism from anti-racism.

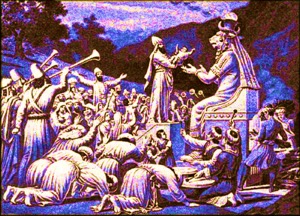

The Poisonous Religion of the Ruling Class

Today’s fraudulent multiculturalist faith fragments society—and fractures the psyche.

Multiculturalism has an unexpected connection to another of the great challenges to America’s civic order: social atomism.

Both the state and the ever-expanding market tend to reduce individuals’ reliance on the other human beings who are nearest to them. This is a good thing up to a point, but the solvent properties of big government and global markets have no natural limit short of society’s total decomposition. The natural and traditional ties between people are subjected to a constant acid bath.

Yet society does not completely dissolve because it is not bound together merely by ties of function. Affection itself counts for something, and a web of affections—which is one aspect of what social institutions such as families and churches and political units are—can find new functions for itself if it is deprived of the old ones. But this is where multiculturalism is most insidious: far from preserving such webs, it tears them to shreds at the psychological points of contact that matter most.

For decades now, conservatives have criticized welfare statism for its atomizing effect on society. Programs intended to aid single mothers, their children, and the poor, for example, have the effect of making society’s vulnerable more dependent on government and less connected to the men and institutions who would once have provided for them: husbands and fathers, faith communities, extended families and ethnic neighborhoods, and civil society writ large. As men are relieved of responsibility, they become more irresponsible, and the duty to care for their children comes to be enforced less by social sanction—once seemingly all-powerful—than by the machinery of the justice system.

Entitlements of all kinds, most of which are not aimed at the neediest Americans, similarly crowd out social capital. Material needs are met, and in some sense freedom has increased (freedom from commitments other than to the state), but the social and emotional supports of the intact family and woven community are gone. Outside the family, our culture of celebrity individualism is indistinguishable from underclass irresponsibility. And corporate America’s preference is for interchangeable workers and consumers, distinguished only by their specific mix of preconceived appetites. The result is a lonely, anomic country.

But multiculturalism surely can’t be part of the problem: after all, isn’t identity politics about belonging to a group rather than being a loose individual tied only to the state?

One might imagine so—except that multiculturalism is a fraud. Multiculturalism is a substitute for organic identities connected to neighborhoods, religion, and class: real friends, places, and economic conditions. The group identities with which multiculturalism is concerned are actually ideological identities in racial, cultural, or sexual disguise. Evidence of this is to be seen in the fact that white liberals are more devoted to multiculturalism than the non-elite members of any minority typically are.

Multiculturalism means more in the faculty lounge than it does on the streets, and its evangelists who proclaim the faith and condemn heretics hail overwhelmingly from the ranks of the educated. Multiculturalism unites and militarizes the members of an educated class whose education chiefly concerns their own fitness to rule—on account of their greater enlightenment and moral sensitivity, of course, but also their recognition of the fitness to rule in other rulers. They respect the right idols, the right kinds of authority for their class.

Multiculturalism is a class ideology, but not in a purely economic sense: it binds a group that is distinct in its position within the social hierarchy together and provides it a common spirit. It is the religion of the ruling class. Google provided a telling illustration of this when it tried to suppress the Claremont Institute’s criticism of multiculturalism. Google is not weak, oppressed, or lacking in power, wealth, and social standing—just the opposite.

The U.S. has a highly democratic society with an expansive view of social equality. A religion or group ideology that emphasizes hierarchy is therefore bound to provoke outrage. Multiculturalism avoids that by being a belief system which Google executives and university administrators, government officials and millionaire celebrities alike can enforce in the name of the weak, rather than a transparent assertion of their own social superiority. More specifically, multiculturalism uses racial and sexual identities as weapons in a war against class enemies: the historically guilt-ridden Protestant middle, which remains guilt-ridden whether or not it’s Protestant anymore; the uneducated (and therefore deplorably uncatechized); and the dwindling number of elite Americans who remember what self-governing liberty is supposed to be.

Beyond supplying a mythology of justification for power and camouflaging class warfare, multiculturalism, crucially, identifies an enemy. The enemy is white, Christian and Jewish, heterosexual, “cisgendered,” bourgeois, and consciously or habitually conservative. In short, the enemy is what were once the country’s mainstream and typically majority identities—and in fact, still are. This definition of the majoritarian enemy makes sense if multiculturalism is understood as a small and elite class’s effort to assert and maintain power over a larger populace that would otherwise resist its rule.

The multicultural clerisy—the intellectuals and media figures, including social media activists, who formulate and propagate the doctrine—is not by itself the country’s ruling class. The spiritual power it wields has to be employed in tandem with the temporal power of the plutocracy and the administrative class. Those temporal elites rest their claim to rule on technical expertise and a supposed natural relationship to wealth-creation. Yet such claims, widely believed though they may be, are lacking in the moral dimension. The clerisy supplies the ruling classes’ missing moral legitimacy.

“Woke capitalism” should thus not be a surprising phenomenon—it’s a logical formula for aggregating and legitimizing power. Its multicultural component softens the moral case against plutocracy (Google and Facebook are on “the right side of history”), and it demonizes the older middle class and Protestant patrician alternatives to the present system of power.

Herein lies the greatest harm that multiculturalism inflicts. That a self-serving elite would devise an ideological weapon with which to enforce its rule may be lamentable, but it’s not at all exceptional in human history. What is exceptional is the collateral destruction caused by this particular weapon: it splits not atoms, but the psychological bonds of human society.

A well-ordered political community consists of many “little platoons,” chiefly families and localities, which tend to their own affairs to a large degree—rather than being dependent on a remote tutelary power—and are wellsprings of moral and political strength for the nation as a whole. These groups can act as a check on abusive power from above, to be sure, but they also stabilize higher levels of power by keeping the responsibilities of those upper levels limited and manageable. Legitimacy is threaded throughout the system, from the family itself to the local informal powers of society to government at each level.

Churches, neighborhoods, families, and local institutions of all kinds might be besieged by competing institutions like the welfare state or the global market, but they are not without defenses derived from their members’ loyalty. What multiculturalism does is to delegitimize that loyalty by recasting it as simply a form of white supremacy or religious bigotry. Almost all subsidiarity loyalties have to fall into such categories, for the simple reason that the country has always been majority white and Christian.

Even traditional left-wing working-class politics is now delegitimized in this way. More than a few woke Twitter personalities have claimed that the very term “working class”—even when Bernie Sanders uses it, and certainly any time Trump does—is really code for “white.” Working-class solidarity is therefore suspect, and a fortiori religious liberty and federalism and everything else that might organize and protect the wrong sorts of minorities and non-ruling classes is illegitimate. Borders too, of course: the principle of having loyalty to the people near you with whom you interact regularly and share a bond of citizenship must be replaced with distant and abstract loyalties—to humanity, to multiculturalism, and to maximally efficient global markets. The nuclear family itself can no longer be a nexus of loyalty and solidarity—it is only a collection of individuals who express ideological identities, not intimate natural relationships.

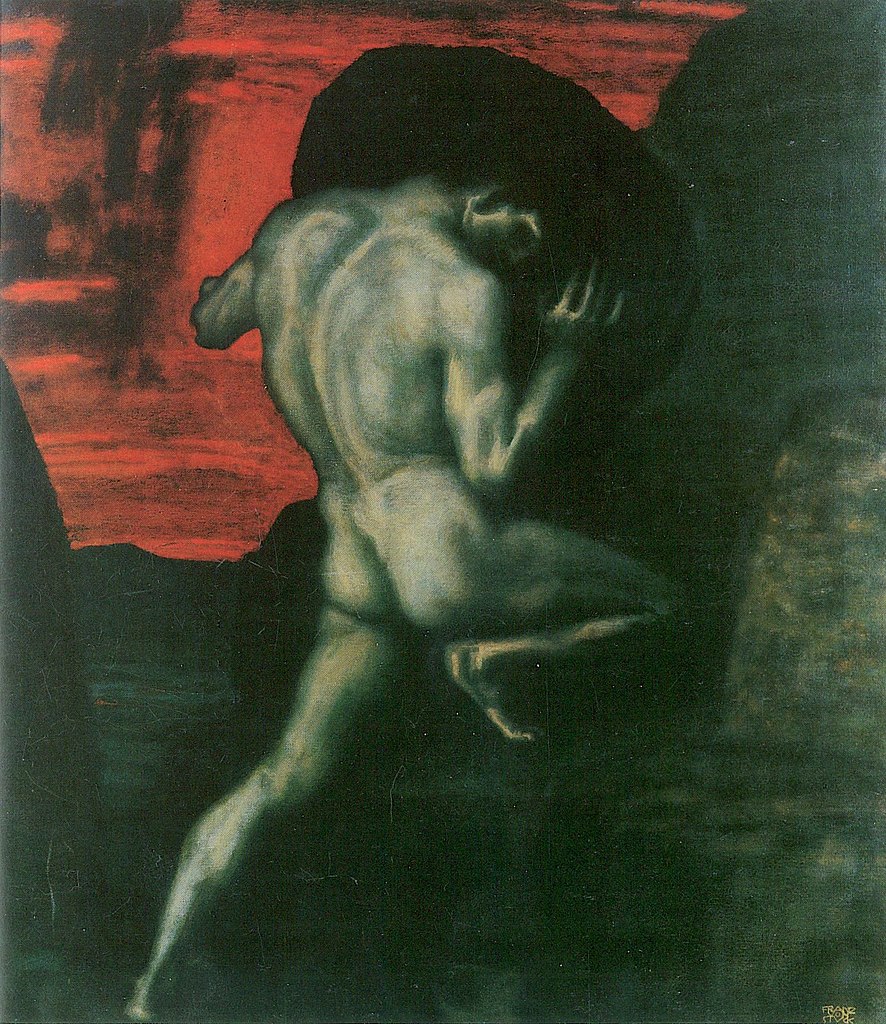

Smash an institution, take away its function, and still its ghost may haunt you—many a people conquered, scattered, or enslaved has reconstituted its way of life after the burning of its temple or the sack of its cities, as long as the nexus of affections and loyalties remained intact, in memory if nowhere else. Multiculturalism, which is a petty ideology of power, does graver damage than its adherents may intend when it deprives Americans of the psychological as well as social context in which human beings and citizens are formed. With affections no longer bound to traditional, natural, and proximate relationships, the individual is left to attach feeling to almost anything, including nihilistic violence and ideological extremism.

But most often the unmoored feelings attach to nothing at all—leading not to a situation in which plutocracy and clerisy enjoy uncontested authority, but to one in which there is no legitimacy to be had anywhere. Tocqueville’s Old Regime and the French Revolution warns of what happens when the intricate structure of authority dissolves and society is atomized and administered from above. Sooner or later this entropy consumes even the plutocrats and ideologues who brought it into being, and a new, possibly crueler form of rule emerges.

Ideology and power are in the end simply no substitute for real human relationships of place, faith, work, and love. Yet by poisoning those relationships at their psychological wellsprings, multiculturalism destroys what it can never create: the clusters of affection necessary for the well-ordered and good society.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Militant evangelists for ruling-class values rotted our foreign policy out from the inside.

The multiculturalists know who they are and what they want. Do We?

Its ideologues are careful to conceal their transformation of higher education into an anti-Western, post-American seminary.

The progressive Left's cluster of demands is an ideological deformity, not a comprehensive doctrine.

The legalists’ logic of proliferating special classes destroys their fantasy of social unity.