To win, the Right must distinguish anti-Americanism from anti-racism.

An American Heresy

The progressive Left's cluster of demands is an ideological deformity, not a comprehensive doctrine.

Today, according to Claremont Institute President Ryan Williams, “multiculturalism and its politics of identity pose an existential threat to the American political order comparable to slavery in the 1850s or communism during the Cold War.”

The stakes transcend the future of liberal democracy in America: “If we do not reverse multiculturalism’s advance, it will continue to undermine our country and constitutionalism, destroying the possibility of a common good and a life of civic peace. Indeed, multiculturalism threatens to take down western civilization as a whole.”

Therefore, we must diagnose the scourge accurately: “This fight, equal parts intellectual and political, must start with comprehension of the nature and scope of the problem. We must understand what multiculturalism is, its effects, and what we ought to do about it, starting at home.”

The proper diagnosis, contends Williams, is that multiculturalism is an all-encompassing evil. It “is a comprehensive ideology, demanding obeisance to a rigid system of justice, vices, and virtues.” It “is a worldview—a regime, in the classical sense; a political and cultural way of life all wrapped up in one.” Whereas American constitutional government undertakes to make “out of many, one,” multiculturalism is a revolutionary doctrine that “seeks to divide and conquer Americans, making many groups out of one citizenry.” Consequently, “multiculturalism (and its politics of identity and political correctness) is anti-American.”

I welcome the determination of Williams and the Claremont Institute to protect the nation against the deleterious ideas and illiberal political aims of the purveyors of identity politics and political correctness. But I worry that the Claremont campaign proceeds from a flawed understanding of the ideas Williams hope to defeat and misconstrues the imperatives of prudence arising from the regime he wishes to preserve.

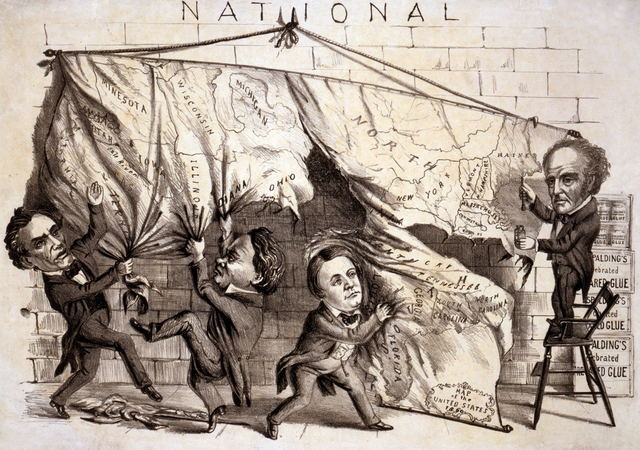

It is a theoretical and rhetorical error, I believe, to liken multiculturalism to slavery and communism. A brutal institution that in America acquired the force of law, slavery endured for more than two centuries and was only finally abolished by means of a terrible civil war that took more than 600,000 American lives. A form of totalitarian rule, twentieth-century communism swallowed nations whole, impoverished masses, and caused—through war, famine, and the relentless cruelty and repression of the routinized police state—approximately 100 million deaths.

In contrast, the ideas that Williams groups under the multiculturalism label present an incoherent cluster of demands for power by resentful members of the elite which masquerade as a quest for social justice by the disadvantaged.

The strange brew of multiculturalism and identity politics is not a comprehensive ideology. It lacks an account of human nature and a conception of human flourishing.

Nor is it a regime. When they bother to pay attention to who should rule, the structure of government, and the highest aims of politics, its devotees offer little more than infantile expostulations, naked preferences, and utopian platitudes.

And multiculturalism standing alone is not intrinsically anti-American, though many who parrot the slogans of identity politics do resent American power and have blinded themselves to America’s remarkable accomplishments.

It is better to understand the progressive left’s apotheosis of certain favored group identities as a deformation and radicalization of an integral element of America’s constitutional whole and therefore as an American heresy.

Many of those who fled England in the 17th century for the new world and who, in the 18th century, fortified the intellectual and political infrastructure of the fledgling nation, favored toleration in part because it would preserve group attachments. With the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, Americans formed—in accordance with what became the nation’s motto, e pluribus unum—out of many, one. This political unity was grounded in individual rights. And it was infused with the expectation that in exercising those rights individuals would maintain a diversity of associations that, provided their members observed laws that applied to everyone, would be free to pursue the good as they understood it.

America not only forms out of many, one. It also preserves within one, many.

I agree with Williams that it is urgent to learn from the Founders’ enduring wisdom and Lincoln’s magnificent prudence. I would begin with the “lesson of moderation” that Alexander Hamilton provides in Federalist 1 concerning the permanence within democracy of passionately held and painfully wrong opinions. I would stress James Madison’s shrewd observations in Federalist 10 about the inevitability in free societies of “faction”—that is, groups indifferent or hostile to particular individuals’ rights and to the larger public interest. And I would turn for inspiration to Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, which, after four years of devastating bloodshed, called the nation together “with malice toward none, with charity for all.”

The struggle in the United States against the dangerous delusions of identity politics is crucial. It should be embarked upon with the goal of persuading fellow citizens, not crushing adversaries.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Militant evangelists for ruling-class values rotted our foreign policy out from the inside.

Today’s fraudulent multiculturalist faith fragments society—and fractures the psyche.

The multiculturalists know who they are and what they want. Do We?

Its ideologues are careful to conceal their transformation of higher education into an anti-Western, post-American seminary.

The legalists’ logic of proliferating special classes destroys their fantasy of social unity.