To win, the Right must distinguish anti-Americanism from anti-racism.

The Institutional Origins of the Multicult

The legalists’ logic of proliferating special classes destroys their fantasy of social unity.

In his powerful essay, Ryan Williams describes multiculturalism as a “regime”—“Multiculturalism is a worldview—a regime, in the classical sense; a political and cultural way of life all wrapped up in one.” And what is a regime? In 1776, John Adams put it this way: “The foundation of every government is some principle or passion in the minds of the people.” Moreover, he added, “The noblest principles and most generous affections in our nature, then, have the fairest chance to support the noblest and most generous models of government.” The trouble with multiculturalism is that it is neither noble nor generous—and it is threatening to become the principle at the heart of modern American life.

By multiculturalism, Williams does not mean merely an embrace of or recognition of the “the presence of many cultures, races, or ethnic traditions” among American citizens. On the contrary, by “multiculturalism,” Williams means a particular understanding of what America is about, an Americanism which is perhaps best summed up by Al Gore’s famous “Kinsley gaffe,” declaring that E pluribus unum means “Out of one, many.” This idea threatens to balkanize America into a vast empire of warring tribes. It is an Americanism that regards “assimilation” as a “racist code word,” as a 2018 essay in Slate put it.

Responding to Williams, Peter Berkowitz calls this kind of multiculturalism a “heresy.” It is a misguided understanding of American pluralism. But I do wonder if the focus on doctrine is leading us astray, for the legal and institutional roots of the problem run deep. It is worth considering, on this score, the degree to which our warped multiculturalism grows not from a particular set of ideas but out of the orders and laws under which we currently live.

Here, John Fonte helpfully underscores the legal-administrative element of the story. “In 1977,” he writes, “the U.S. Census created five ethnic categories that established an official diversity paradigm within American administrative and bureaucratic law: Spanish surname persons who became Hispanics or Latinos; Blacks later called African Americans; American Indians (later called Native Americans) and Alaskan natives; Asians and Pacific Islanders; and Whites. All of these artificial categories consist of people from widely divergent cultural backgrounds.” As Fonte notes, these categories serve “the purposes of the diversity project by promoting victim group consciousness, fostering an ethnic-racial spoils system.”

All too true. Yet the source is deeper, and more problematic politically. Behind the rise of these identity/census groups, and the diversity bureaucrats and the identity industry, is the black letter of our civil rights laws. Because of the very real failures of America to live up to our ideals, the 1964 Civil Rights Act created an unprecedented intrusion into civil society. In essence, it made almost every business a “public accommodation” that was prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, sex, and other specific categories. Americans are still free to associate with whoever they want for whatever reason they want, except that we now have special restrictions and obligations that apply to members of “protected classes.” Since 1964, our bureaucrats have added to the list of protected classes. It is no coincidence that our “protected classes” are, roughly speaking, the teams we see in “intersectional” politics and culture. The law itself is a major cause of this ever deepening division in American life.

What results is an ongoing attack on individual merit and on the concepts of merit and achievement more largely, associating both with “racism” and, hence, associating opposition to them with civil rights.

Consider two examples from decades ago, and one from today. In the early 1990s I got a real estate sales license in New York state. For many years now, I’ve saved the information sheet, for it had a howler: “Numerical scores are not given to prevent possible discriminatory employment practices based on achievement levels.” Around the same time, Dinesh D’Souza noted in his Illiberal Education, someone on “the university planning committee” at the University of Pennsylvania mentioned her “deep regard for the individual and my desire to protect the freedoms of all members of society.” She was smacked down verbally, and told that her concern for the individual was “a RED FLAG phrase today, which is considered by many to be RACIST. Arguments that champion the individual over the group ultimately privilege the ‘individuals’ who belong to the largest or dominant group.” Both of these cases reflect the idea of “social” justice that our civil rights law teaches to this day by creating “protected classes” of Americans who get special protections. Today, executives in the New York City schools report diversity training now teaches that “White supremacy is characterized by perfectionism, a belief in meritocracy, and the Protestant work ethic.”

Where does this nonsense come from? “Disparate impact”—the idea that if the percentage of minority groups in, for example, a fire department is different from the percentage of minorities (members of “protected classes”) in the population at large then we should assume that the result grows from invidious discrimination—began as a way of enforcing the Civil Rights Act. In time it became an ideology of supporting group rather than individual rights—one of the main mechanisms by which civil rights was transformed into multiculturalism. This is what happened when the effort to prevent discrimination against “protected classes” met the administrative state in particular, and administrative bureaucracy in general. The institutions and the ideology reinforce each other.

All that helps us to see the dimensions of the challenge we face. When we combine the moral prestige of the Civil Rights Act, and Civil Rights movement, we see the reason for the moral passion this new multicultural politics generates. All conventions, in time, come to seem normal. I suspect that many Americans still understand that protecting individual rights, rather than multiplying group rights, is what America is about. And what, if not the focus on the rights and responsibilities of individuals has, over the centuries, made the case for the rights of all individuals, Black and White, male and female, if not the focus on individual rights? Most Americans, I suspect, understand that multiculturalism, defined as Williams defines it, attacks that idea, and threatens the rights of us all. Similarly, I believe most Americans still want us to assimilate to a common citizenship. But if the law itself, combined with our institutional apparatus, is teaching a contrary lesson, the challenge is indeed greater, for there is a legal undertow pulling our self-understanding in an unhelpful direction.

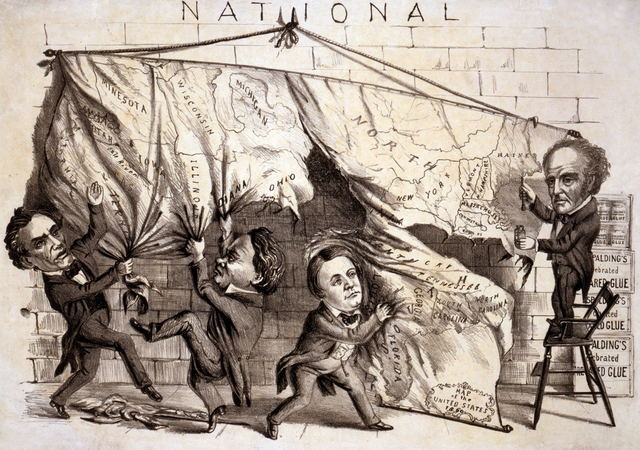

The “heresy” of multiculturalism is burrowing deep. I fear that many among the rising generation take identity politics as a given. The result is that those of us who wish to preserve the regime we have inherited from the Founders and Lincoln have a great challenge. Observing the Missouri Crisis, and the resulting compromise line, Thomas Jefferson foresaw a catalyst for Civil War. “A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated,” he wrote, “and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.” Multiculturalism presents us with a demographic line rather than a geographic one, and yet there is a parallel. John Judis and Ruy Teixiera’s Emerging Democratic Majority may or may not be an accurate political prediction. But if one of our political parties becomes the party of “protected classes,” it is likely to produce the kind of civil discord that the U.S. has not seen in quite some time, as each election, and each heated political contest, will drive the line between the two tribes ever deeper into American political, cultural, and social life.

One hopeful sign is that the myth that all who are not “White” are on the same “side” is under pressure. After all, multiculturalists already concede that not all “minority” groups have identical views and interests. As those of us following the scandal of discrimination against Asian-Americans at Harvard are well aware, their insistence that those views and interests are nonetheless “intersectional” is under considerable pressure. On the other hand, while I hope I am wrong, I sense in the younger generation there a cohort of Trump supporters who simply view the president as a vehicle to fight for their group in the complex scrum of identity politics, instead of viewing him as part of the fight to preserve the principles of 1776.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Militant evangelists for ruling-class values rotted our foreign policy out from the inside.

Today’s fraudulent multiculturalist faith fragments society—and fractures the psyche.

The multiculturalists know who they are and what they want. Do We?

Its ideologues are careful to conceal their transformation of higher education into an anti-Western, post-American seminary.

The progressive Left's cluster of demands is an ideological deformity, not a comprehensive doctrine.