To win, the Right must distinguish anti-Americanism from anti-racism.

From Global Cop to PC Police

Militant evangelists for ruling-class values rotted our foreign policy out from the inside.

Ryan Williams’ essay on multiculturalism, identity politics, and political correctness makes a significant connection to America’s past several decades of foreign policy failures. I was reminded of a turn of events that, in one sense, started it all. In late 1990, the U.S. military shipped soldiers—female soldiers—to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in response to Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. According to a biography written by Omar bin Laden, Osama bin Laden’s son, the presence of female soldiers in Saudi Arabia represented, to Osama, a complete humiliation of the country and its Muslims.

For Americans, this reaction comes off as completely bizarre. Why should the mere presence of female troops matter? But the question of why this might matter rationally speaking is irrelevant when considered from the perspective of a rival value system with a different conception of the right ordering of society. And as it happened, this seemingly insignificant incident put Osama bin Laden, who had worked with the Americans just a few years earlier to oust the Soviets in Afghanistan, in deep conflict with both the Americans and the Saudi royal family. His outrage spiraled into a decision to flee the Kingdom and set him on a trajectory to mastermind the anti-American plot that would upend the Western world on September 11, 2001.

After 9/11 came the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Top U.S. officials appeared to sincerely believe not only that American values should be universalized, but that they actually already were universalized. Others abroad needed only to be encouraged, or forced, to recognize the truth. If one looked closely, they argued, at the souls of Iraqis and Afghans, one would find the American spirit gestating within them; they just needed a regime change to allow this fully-formed New American Man to spring forth. What the Iraqis wanted, the argument ran, was not a functional state, but freedom and (social?) justice, because everyone can’t help but want those things.

At the time, this sort of ideological imposition was broadly seen as a Manichean crusade bringing goodness and light to benighted realms of evil. In reality, it is more roughly equivalent to the exertions of Jonathan Swift’s Little Endians, who in Gulliver’s Travels started a war with the Big Endians about the universally proper way to break open a boiled egg. Many countries don’t appreciate the State Department dictating secular Western values to them and then being dragged through the mud of the Western press regarding compliance with norms that have, ironically, only become sacrosanct within the past decade.

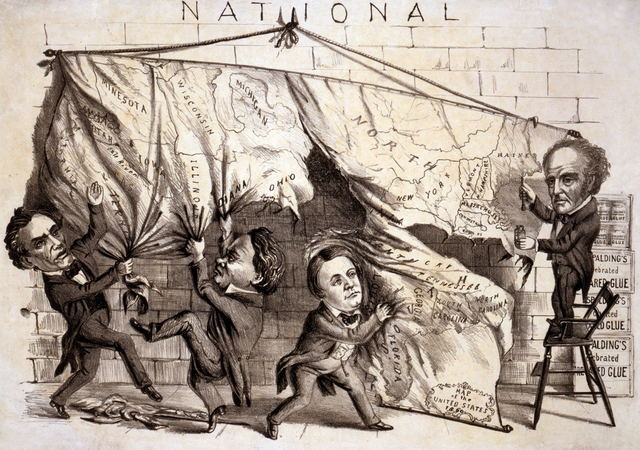

One of the benefits of being a hegemon is the ability to subjugate client states by replacing their values with your own. America enjoyed this power throughout the 20th century. But as the Iraq debacle and bin Laden’s 35-year ordeal with the U.S. reveal, America’s poor foreign policy track record over the past two decades maps suspiciously well onto America’s mounting failures to impose “correct” values on client states.

Given this track record, it makes sense that a growing number of voices would urge the U.S. to limit the scope of its interests to economic and security considerations, rather than full-scale values evangelism, in the name of human rights, LGBT rights, feminism, liberal democracy, individualism, or whatever else.

Not enough has changed since 2001. In 2019, some top U.S. officials are still acting as if Venezuelans, Iranians, and others can’t wait for their country to be like America—often, the same sorts of officials working whatever levers they can to encourage military intervention. This time, however, American state capacity is so degraded that it can’t even pull off something that would deserve the name of “failed coup” within its own hemisphere. This has not gone unnoticed by American client states and potential hegemonic rivals.

Since delusional organizations are often incapable of making serious course corrections, we shouldn’t expect that pointing out these dynamics will straightforwardly lead to change. Instead, the most likely outcome is that America will continually lose power on the world stage in proportion to the rise of a credible, competent, and less invasive rival hegemon.

Absent the rise of a new foreign policy class dedicated less to evangelizing values cooked up by domestic elites than they are to securing the interests of the state and American society, there is no reason to expect anything else.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Today’s fraudulent multiculturalist faith fragments society—and fractures the psyche.

The multiculturalists know who they are and what they want. Do We?

Its ideologues are careful to conceal their transformation of higher education into an anti-Western, post-American seminary.

The progressive Left's cluster of demands is an ideological deformity, not a comprehensive doctrine.

The legalists’ logic of proliferating special classes destroys their fantasy of social unity.