Without stronger individual character and deeper social cohesion, Americans are poised to stumble away from revival and into revolution.

Why Conservatism Failed

An argument lost.

For many readers of political philosophy—what Aristotle called the master science—the book of the year was Notre Dame Professor Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed. Arguing that liberalism’s success has caused its own failure, Deneen cast today’s moment of institutional reckoning as the inevitable result of the paradoxically illiberal logic at the heart of liberal ideas. “Discontent is growing,” he wrote, “among those who are told by their leaders that their policies will benefit them, even as liberalism remains an article of ardent faith among those who ought to be best positioned to comprehend its true nature.”

“This divide will only widen, the crisis will become more pronounced, the political duct tape and economic spray paint will increasingly fail to keep the house standing. The end of liberalism is in sight.”

This sobering assessment was enough to grab the attention of Barack Obama himself, whose presidency was premised on achieving the exact opposite of what Deneen prophesies and observes. While the former president is doubtless unmoved on the issue of the viability of liberalism, or, as he might say, progressivism, surely he pondered closely Deneen’s view of the fork in the road to come.

Down one path, says Deneen, “contemporary liberalism will increasingly resort to imposing the liberal order by fiat—especially in the form of the administrative state run by a small minority who increasingly disdain democracy.” Down the other, however, is a much different result, ideologically speaking: “some form of populist nationalist authoritarianism or military autocracy seems altogether plausible as an answer to the anger and fear of a postliberal citizenry.”

From an Obama-esque standpoint, Deneen’s counsel is bracingly direct: either take democracy away from the rubes, or they will take democracy away from you. Seeking to discern “a humane alternative to either liberalocratic depostism or the rigid and potentially cruel authoritarian regime that may replace it,” Deneen concludes that “only the barest outlines may be discerned amid a landscape so completely shaped by our liberal age.” Politics, he ventures, will not “return” Americans to “a preliberal age.” Indeed, “we must outgrow the age of ideology” altogether. In its place, new frameworks informed by the experience and practice of “humane life” must be cultivated over time.

Again taking up the liberal-progressive vantage of the former president, the most striking thing about Deneen’s prescriptions is that they fully exclude any explicit appeal to conservatism. In a certain sense, the most important lesson about why liberalism failed is that conservatism simply no longer matters as political-philosophical resource for addressing our regime’s present crisis.

Yet it is now plain that one does not have to be Barack Obama to recognize that programmatic ideological conservatism has fared very poorly during the current stage of the crisis. That conservatism is what Donald Trump ran against and defeated resoundingly—much more resoundingly than he defeated liberalocratic despotism, which, of course, had the benefit of the administrative state on its side in continuing the fight. Today, Deneen’s book deserves a companion piece of sorts—entitled Why Conservatism Failed.

* * *

There are a number of fruitful points of departure for a political-philosophical exploration into why and how conservatism failed. In his recent column on the present crisis, Ryan Williams offers an especially promising one.

Intriguingly, you do not have to be an ideologue of any stripe to follow his reasoning. Today, Williams writes, “we are polarized now about foundational questions of human nature, constitutionalism, and justice. Our cold civil war and partisan rancor will only end when one party finally wins the argument about these fundamentals in a decisive and conclusive victory and uses that victory to solidify and sustain an enduring electoral coalition for a generation or more.”

Notable about this seemingly partisan proposition is a neutral observation at its heart: the most dramatic way in which programmatic conservatism has failed is exactly on these grounds. It presented itself as the one faction or party with the winning argument about how to seek justice in accordance with our nature and our regime. After decades of ups and downs in the late twentieth and very early twenty-first centuries, party conservatism was blown out entirely in the most recent presidential election.

Over those torturous decades, more than just party conservatism failed. The ambitious strain of conservatism that embraced ideological fluidity as the dues to be paid for political influence hit a wall. And the modest strain, stretching in an intellectual tradition from the likes of Christopher Lasch to the likes of Rod Dreher, gained public renown but largely turned away from the crisis of the regime and placed faith in a narrower, localist cause.

So no kind of conservatism in the familiar sense has flourished amid the current crisis of liberalism, even though the very purpose of conservatism was to serve as the grand alternative political philosophy to liberalism, the only one capable of putting our whole regime, and our whole people, to rights.

What explains this uncanny turn of events?

* * *

One approach might begin with recognizing that conservatism can be criticized (or defended) as simply a particularly qualified form of liberalism. As Deneen has it, in the ancient sense, liberty meant freedom “from enslavement to one’s own basest desires,” while, for modern liberals, the true meaning of freedom was the unfettered pursuit of “whatever they desired.” One way conservatism has failed is in running around trying to manage the tension between these two theories of liberty.

On that score, much controversy has swirled this year around Deneen’s contention that this modern liberal understanding is woven into America’s founding itself. But critics who have attacked that claim on economic instead of political-philosophical grounds have not been persuasive. The best way to defend the Declaration and the Constitution is not by invoking Adam Smith’s invisible hand, much less Friedrich Hayek’s notion of spontaneous order. The Founders understood the United States to be a commercial republic, and recognized the inherent value in advancing commerce in accordance with the strategic and material interests of the union. They did not believe, and did not have to believe, that free markets were an ideal Platonic form always and everywhere the same regardless of time, place, culture, and other conditions.

This is of particular weight in assessing the failures of conservatism because it shows the Founders did well in squaring the economic reality of their age with the political and philosophical imperatives for pursuing justice in any age. Free markets simply meant something different in the 1790s than they did in the 1990s—in part because of huge cultural changes driven by the inner logic of liberalism, but in substantial part because of the technological environment in which the Founders had to ground a just and durable republic.

In fact, the cultural logic of liberalism should be seen to have made such stunning gains because of how well it comported with the new technological environment that arose in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Burkean conservatism was very poorly suited to winning hearts and minds in an ideological match against progressivism, imperialism, fascism, socialism, and communism because the milieu of machines and technologies in which Western people processed reality opened vast and dangerous vistas of imagination.

Successful statesmen in the modern Western tradition following on what the Founders had wrought grasped this—and found forms of rhetoric and rule that recurred to republican forms and virtues from within the dominant milieu. Lincoln mastered the telegraph, Churchill the radio, Reagan the TV. But these were characteristically brief interludes in an ever-strengthening drumbeat of liberal-progressive progress, which often marched ahead through the dominant technologies. When Al Gore was understood to claim personal responsibility for the internet, he and his audience were more or less in accord that liberalism and modern technology were seen and experienced as two facets of the same phenomenon.

But as we are now seeing every day, that conclusion was a fundamental mistake. The internet has not only peeled away from Al Gore’s imaginings. It has betrayed them. And with it, it has opened up new space in America’s everyday milieu for alternatives both to failed liberal ideology and failed programmatic conservatism.

* * *

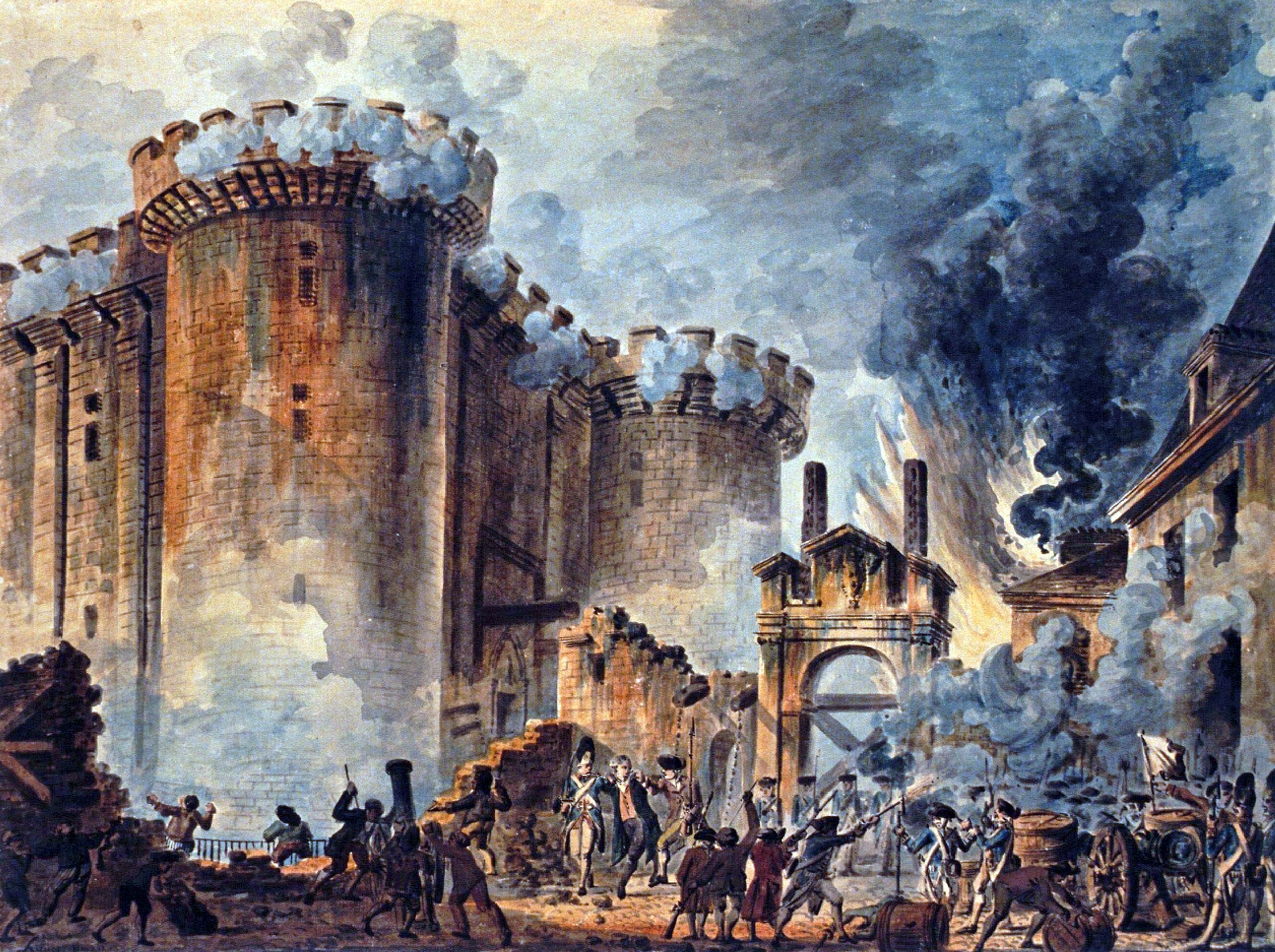

This wake-up call did take a moment to arrive. Even with televangelism and cable television at its disposal, conservatism was not able either to decisively defeat liberalism at the level of our technological milieu or to offer, at the level of politics, a broadly accessible set of practices alternative to liberal technocracy. The realm of possible experiences had become too totalized and closed off. Even appeals to recovering the wisdom, perspective, and insight of the Founding struggled against the battlements of the administrative state and the wealthy interlocked institutions of the interpretive and communicative elite.

Under the surface of our increasingly rote partisan conflict, however, the ground of possibility was shifting. Technological change opened Americans’ minds to a set of connected issues touching on the fundamental questions of our nature, our regime, and justice. The threat of robotic or algorithmic masters became concrete, not just a thought experiment. The opportunity to communicate and exercise agency completely outside of the technological framework of liberal rule became real, not just an object of fantasy. A compelling answer to the now-what question left hanging by end-of-history liberalism at last came into view—warts and all. Conservative rhetoric gestured in the direction of a fundamental alternative to liberalism, but the new shift in the ground of everyday reality made the construction of an alternative something people can touch and taste. Yesterday’s battle over ideas gave way to today’s battle over reality.

In this new climate, where something that is neither ideological liberalism nor conservatism has the momentum and initiative, it is possible again to recur to fundamental questions of restoring the vitality of our regime, adopting new policies to strengthen what was present at our origins. While politics alone cannot reach into the past and drag back what once was, we are already seeing how the shift in the ground of reality is bringing back patterns of thought and forms of experience that belong to a deeper past than that of Franklin Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, or Stephen Douglas.

On this new ground, unlike the exhausted ground technocratic liberalism had monopolized, it is again possible to achieve a decisive and conclusive victory on the fundamental questions of justice and flourishing. While the conflict over the political philosophy ingrained in our founding is likely to be fierce, neither twentieth-century liberalism nor twentieth-century conservatism is likely to be the victor. For just that reason, it is once again essential to our future fortunes that our founding principles remain intact.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The era of Progressive mythology is over.

On the gloating and the gloaming.

First, focus fire on America's radical fifth column.

The vindication of "The Flight 93 Election"?