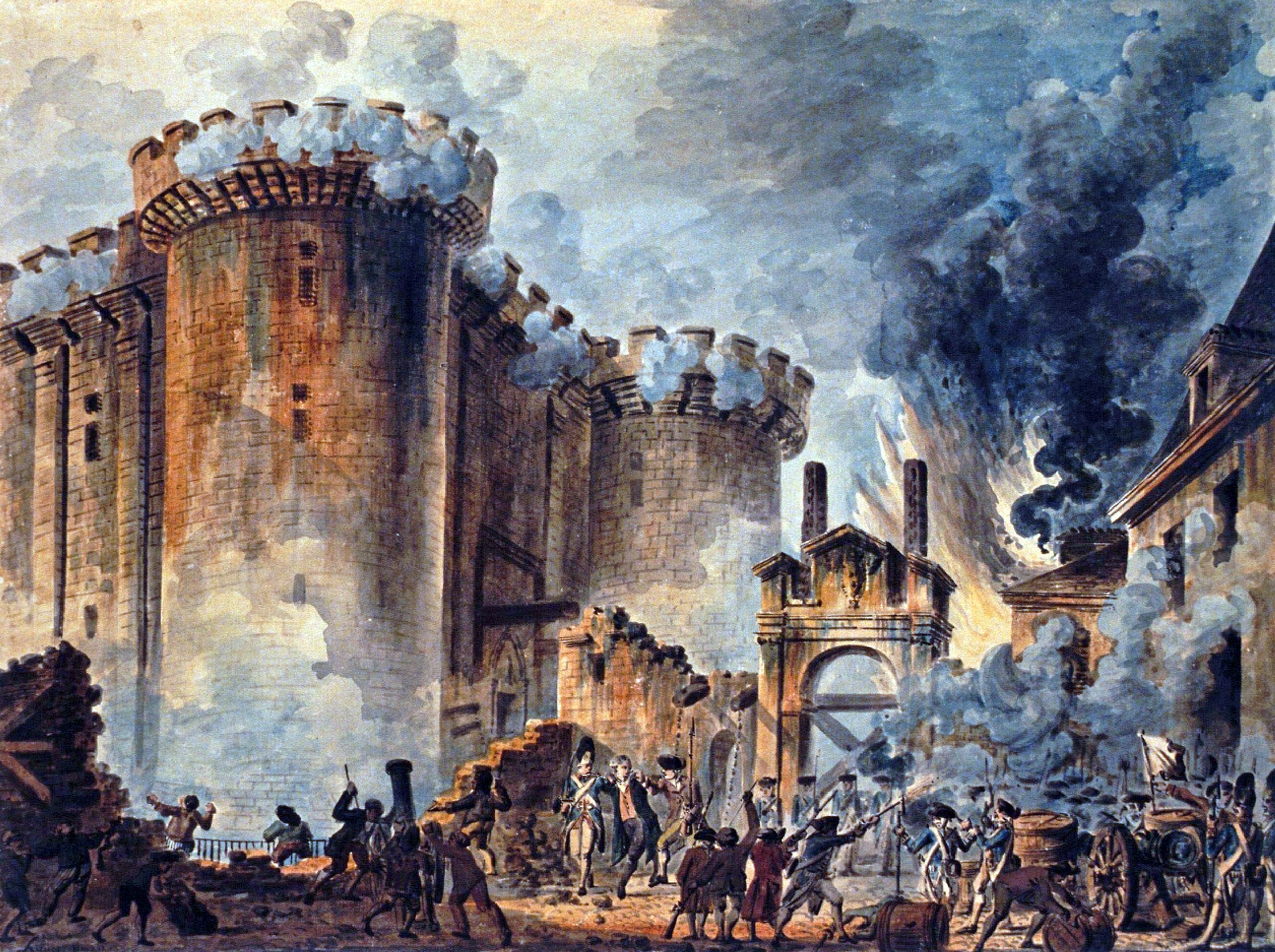

Without stronger individual character and deeper social cohesion, Americans are poised to stumble away from revival and into revolution.

The Twilight of the NeverTrumpers

On the gloating and the gloaming.

Once upon a time, like so many other young conservatives, I used to read every word Jonah Goldberg wrote. I mean no disrespect when I say that there was a time—for those who don’t remember—when The Corner at National Review was not only a must read, but a page to be refreshed daily with reckless abandon.

What set Goldberg apart was not only his intelligent mind and talent for writing, but his perception of what the new online medium demanded. Unlike so many others who either ignored the new medium or tried too hard to succeed within it, he was willing and able to use his considerable skills to meet its demands.

Inherently discursive, digital communication allowed for a simultaneously serious and playful form of writing. To the print world the tone and pace of digital seemed decidedly uneven, if not grossly unprofessional. In the beginning, it wasn’t taken seriously enough, and online publications and “blogs” were often decried as ephemera, a silly passing fad. What the critics missed, among other things, was what intelligent audiences wanted.

Goldberg had the self-effacing humor and humility to delve in regardless of the raised eyebrows, bringing his wit to bear in a way that eventually made him a kind of crossover star who could write much more seriously than TV and radio pundits, yet much more widely, and to a much larger audience, than your average intellectual or policy wonk.

I was an overjoyed fanboy when—with the quip, “Never get caught up in a Straussian’s grill”—Goldberg linked to the first installment of a series of blog posts I wrote for the Claremont Institute while in graduate school. The ensuing debate, which defended Harry Jaffa and Claremont from charges of neoconservatism, among other things, involved Jaffa’s first blog post at 88 years young and gained record views for that now defunct publication, largely because of Goldberg’s friendly attention.

This is my first written contribution as Editor of The American Mind, the new online publication of the Claremont Institute. Things have changed. Over the past twelve years, as the Bob Dylan song goes, “there’s a lot of water under the bridge, and a lot of…other stuff…too.” Some of that “other stuff” included the continuing disillusionment of many, like myself, who had begun to give up on the Right.

Few of us switched sides. But we saw, with increasing clarity, the corruption rotting out the core of American political life as both Left and Right chanted stale, Cold War-era mantras at each other while going through their outdated motions. We watched in frustration as this dynamic carelessly ceded ever more of our political and cultural life to an increasingly ravenous, identity politics-driven Left that brooked no dissent and took no prisoners.

Upon realizing the horrendous errors of the response to 9/11, even former fanboys grew impatient with the Republican party’s smug, lockstep refusal to admit a single mistake. We began to quietly question the establishment Right’s weak and easy utilitarian rhetoric of economic efficiency, and its stubborn refusal to address underlying issues of national principle and purpose, justice, and the common good.

We furtively asked each other, after perceiving we might be in the company of a fellow cynic, “What, exactly, do all these thinktanks and academic centers even accomplish anymore?” We grumbled about having to remain silent for the sake of the team as establishment leaders regarded our questions and ideas as too radical or naïve. Oblivious of the brewing backlash within, they had little desire to develop talent outside the usual safe, lukewarm, flattering pools, all the while ignoring increasingly sordid reality on the ground.

There are even deeper, overarching reasons for this discontent, some of which my colleague, James Poulos, Editor-At-Large of The American Mind, details in his contribution to this week’s feature (“Why Conservatism Lost”). I came to Claremont Graduate University in part because of reading Charles Kesler’s 1998 Bradley Lecture entitled, “What’s Wrong With Conservatism”; twenty years later, it reads as a prophetic warning. Kesler asked questions that most on the Right never got around to answering—a fundamental failure that led directly to its present discontents.

It becomes hard to care too deeply about anything that refuses to save itself. And over the last decade, people like myself fully expected the Right to die by its own slow hand.

We still cared deeply, of course, about American principles and purpose—our common good. We took note when the cyclical dissatisfaction of the electoral base produced folk heroes and movements that took on the media squarely or ran against the grain of this or that establishment Republican dogma, if only to rise and fall in their respective turn. Even as these tides swelled in strength, they never grew serious enough to merit more than passing paroxysms of enthusiasm.

We remained on the right out of principle rather than policy, out of default instead of desire: a never realized, inert “movement” without form.

This is why, even if I did not take Donald Trump seriously enough early on, when Michael Anton wrote “The Flight 93 Election,” he roused me and others out of our reluctant apathy.

“Flight 93” was a sign of life—a bold proclamation of the crushing truth of reality pressing down upon increasingly brittle establishment rhetoric. For obvious reasons, the reaction to “Flight 93” focused obsessively on Trump. But even if we weren’t entirely sure about Trump, readers like me heartily agreed with his searing description of Conservativism, Inc. as the Washington Generals—the habitual losers—of American politics. Anton said out loud what many had long felt in their bones: the Right no longer knew how nor wanted to win, having long since habituated itself to defending established interests.

Which brings us back to Jonah Goldberg. In a new column, Goldberg laments that, in the wake of the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, “gloating and total war is the new statesmanship.” He goes on to cite, disapprovingly, President of the Claremont Institute Ryan Williams’s argument that “Decisive Political Victory is the Only Way to End This Cold Civil War”; on Twitter, Goldberg rather cryptically pronounces that Williams’s article “is not well reasoned or well-argued.” In his column, Goldberg frets that Williams claims “the middle has collapsed, the parties are pulling farther apart, and it’s Flight 93 for as far as the eye can see.” What’s worse, “[t]he left largely sees this situation this way, too.”

So they do. Are they wrong? Isn’t the Left simply acknowledging the bald-faced reality that is largely of their own ideological making? True statesmanship confronts the circumstances as they are, not as we might wish them to be. Statesmanship must decide when victory requires war, or force of some kind, in situations that necessitate winners and losers.

The alternative to force, of course, is persuasion. There are times when persuasion does not suffice, however, to establish justice—and in such moments of crisis the greatest of statesman have often used persuasion to spur the rightful use of force. In fact, in such times winning is often the best means of persuasion available. To what extent would Abraham Lincoln’s speeches have mattered if the North didn’t win the Civil War?

Of course, war is messy. It inexorably escalates, tempting both sides to throw principle to the wind, to use any means necessary for the sake of winning, and to dehumanize the other side. It risks lasting damage to the alpha and omega of politics—shared principle and common purpose. That is why no sane statesman would choose it willingly.

Nonetheless, there are times when shared principle and common purpose are already in dispute, and the war comes to you.

Goldberg acknowledges that the battle over Kavanaugh had to be fought, but the fact that “many voters rallied to Trump on the grounds that ‘at least he fights,'” troubles him greatly. Yet the “at least he fights” sentiment that Goldberg seemingly finds deplorable isn’t some kind of intrinsic evil. It was echoed by none other than Lincoln himself, who famously told the detractors of General Ulysses S. Grant, without denying Grant’s undeniable flaws: “I can’t spare this man–he fights.” Dan McCarthy superbly develops this point this week in his thoughts on “Consensus as Surrender.”

Goldberg, however, wrestles in National Review recently with his own “misgivings about the price of victory” in the effort to confirm Kavanaugh. He doesn’t like the fact that winning was “the least bad option.” Twisting and turning, Goldberg finds himself “less enthusiastic about the pro-Kavanaugh forces winning” than he was about the Left losing.

Why this anxiety? Goldberg plaintively warns that “there will be bad consequences no matter what, because we now live in a world where sub-optimal outcomes are the only choices available.” But we have always lived in such a world. This is practically the definition of political life in which, to use the parlance of our times, only the gradation of suckitude changes.

Why incessantly lament it so? The most serious reason he gives us is “that everyone feels warranted to respond to [Trump’s] norm-breaking with norm-breaking of their own.” He glimpses what, in our soon to be published collection of essays this month, Angelo Codevilla calls “Our Revolution’s Logic.” The danger of norm-breaking is sobering, to be sure, but it comes with the territory: there is a political war on, and go-along consensus comes with its own risks.

Goldberg knows we just witnessed one of the most brutal, high-profile smears in America’s political history over the nomination of the “safest” establishmentarian pick on offer. He colorfully describes how the media and the aging avatars of the Democratic party attempted to shamelessly stage a sudden death, reality-television show trial as if it were merely a matter of due process.

It’s fair to lament “collateral damage,” of course, and to work to minimize it in the midst of the battle; it’s fair to argue about the best possible route to lasting victory and peace. It’s fair to have preferred another candidate had won the 2016 primaries. But the establishment was not up to the task at hand, and we are now two years on into this administration. The time for existential hand-wringing on the sidelines to prove ones bona fides has long since past. The point is not that Trump is Grant, but that during times when fighting such outrages as we just witnessed is necessary, one doesn’t hold onto lamentations and grudges about the task at hand, or harp on the supposed or even self-evident defects of those in position to lead.

Trump has not assumed some sort of moderate, Schwarzenegger-esque form. His moderation involves picking beloved establishment Republicans willing to stand with him: Kavanaughs, not Kennedys! He has not caused World War III, but provided an opportunity for a sorely needed rethinking of American foreign policy, hampered mainly by the herd-like thinking and recalcitrance of the International Liberal Order uniparty. He has not caused the economy to go into a tail spin by renegotiating trade deals that were always far from free: he’s delivered the tax cuts that the business side of the right has dreamed of for decades. He has not caused the Republican party to lose Latinos forever, but has instead provoked the debate over citizenship and what it means to be an American that this nation has desperately needed to get on with for decades.

The President’s vices, real and imagined, are routinely exaggerated and decried, but his accomplishments are real, regardless of performative hand-wringing from those who needlessly and ceaselessly attack him from without and within.

Regardless of what one thinks of Trump the man, he has given the Right, including both conservatives and the Republican party itself, a chance to think again. His election has broken up the hollow stasis of the American mind, post-Cold War. In so doing, he has given the Right a chance not only to live, but an opportunity to fight for a life worth living. As Williams has written elsewhere, America is engaged in “a fight over what kind of national political life we will choose for ourselves and the next generation.”

Let Goldberg live his truth—I certainly wouldn’t want him to write untruths he doesn’t believe, or refrain from criticism altogether. It is, perhaps, notable that the shrill cries about partisan sycophancy in support of President Trump that he is so deeply concerned about now could be applied to any presidency, and were noticeably absent from his group’s corner in past years. But let that be.

The central problem both parties face is not a matter of tone or rhetoric in the midst of the chaos and confusion—rhetorical and otherwise—caused by the fall of the old modes and orders. The salient fact of the moment is that the race is on to rethink and reground policy in light of our Republic’s founding principles. The Republican party must realign itself with the real needs of real people if it is to survive. There is no going back; the only way out is through.

Something new now struggles to break forth, but as Ryan Williams has declared, this war “will only end when one party finally wins the argument about these fundamentals in a decisive and conclusive victory and uses that victory to solidify and sustain an enduring electoral coalition for a generation or more.”

I don’t necessarily fault good and intelligent people who are puzzled and disheartened by the admittedly disorientating moment, like retiring Speaker of the House of Representatives, Paul Ryan, or the retiring President of the American Enterprise Institute, Arthur Brooks—both of whom appear to want to diminish, and go into the west, or at least a professorship.

And neither do I fault Jonah for taking so much solace in his canine companions these days.

But to paraphrase Samuel L. Jackson to Robert De Niro in Jackie Brown, “What happened to you, man? You used to be beautiful.”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The era of Progressive mythology is over.

An argument lost.

First, focus fire on America's radical fifth column.

The vindication of "The Flight 93 Election"?