The Left's Jan. 6 tactics are nothing new.

A Tale of Two Crimes, Part II

The politicization of the Department of Justice is now beyond question.

On January 6, 2021, former Proud Boys’ Chairman Enrique Tarrio didn’t punch any Capitol police officers, he never “surged” forward to overwhelm Capitol defenses, he never smashed any Capitol windows or destroyed any Capitol fences, he never threw anything at Capitol police, and he never set foot in the Capitol. He never did any of those things because on January 6, 2021, Enrique Tarrio was in Baltimore, Maryland.

You might be surprised to learn this crucial fact considering that the Justice Department indicted Tarrio and several co-conspirators for seditious conspiracy, among other charges, claiming they “very nearly succeeded in provoking a constitutional crisis.” Two years later, following a four-month trial, a Washington D.C. jury convicted Tarrio and the Proud Boys of most of the counts. In August 2023, DOJ argued that Tarrio should be imprisoned for 33 years; the court sentenced him to only 22.

In a previous article (Part I) I showed how the Justice Department wrapped up its prosecution of Colinford Mattis and Urooj Rahman—left-wing terrorists who firebombed a police vehicle—by arguing for trivial sentences despite strong evidence and egregious criminal conduct. But for Tarrio and his co-defendants, federal prosecutors displayed a relentless zealotry not suitable to the rule of law. They overcharged the lead offense, sought every sentencing enhancement no matter how tenuous, argued for consecutive sentences, and then appealed the actual sentence apparently on the grounds that 22 years was not enough.

“Most Analogous”

Seditious conspiracy is the lead charge in the Tarrio case. It consists of various operative clauses that make it a crime to conspire to “overthrow, put down or destroy by force the Government of the United States” or “levy war” against it. Following its enactment after the Civil War, the count was rarely charged. When it was, these heavy clauses were the thrust of the allegations: overthrow, destroy, levy war. At least that was the case before January 6, 2021, when Justice dusted off its lawbooks, scoured the United States Code, and discovered the phrase “or delay the execution of any law” deep in the bowels of Title 18, which became the crux of its case against Tarrio and the Proud Boys.

According to the lead charge in the indictment, Tarrio and his conspirators “delay[ed] by force the execution of the laws governing the transfer of power.” The delay was six hours. The “force” used amounted to destroying one fence and breaking one window—at least that’s what held up at trial (none of it perpetrated by Tarrio). These same facts describe any left-wing activist at any riot in any city in the nation during the interminable Summer of Floyd better than the actions of the right-wing activists on January 6, 2021. The Department required 108 paragraphs to explain what I summarized in the above three sentences. Digging this deep to find a serious crime, the elements of which match relatively unserious facts, is called “overcharging.” It’s done when the government wants to send a message.

Indeed, the crime of “delay[ing] the execution of any law” is sufficiently rare that it is not addressed at all in the federal sentencing guidelines discussed below. Since it’s not addressed, prosecutors were forced to argue by analogy to another crime that is. According to prosecutors, Tarrio’s actions were “most analogous” to treason.

Reasonable people may disagree about the seriousness of Tarrio’s conduct. Some argue it’s merely trespassing, pointing to other similar actions by left-wing protestors who were charged with that crime, and others argue it’s as serious as breaking and entering. But only the ideologically cynical believe that Tarrio’s conduct is “most analogous” to treason.

And what was the “law” that Tarrio and the Proud Boys sought to delay? During the trial, the government argued that the electoral certification process qualified as a “law.” Given that the Capitol riot delayed the certification by several hours, the jury had a hook to find Tarrio and the Proud Boys guilty.

Perhaps you think that the literal application of the statute should be the end of the inquiry. If so, consider that in September of this year, New York Congressman Jamaal Bowman falsely pulled a Capitol fire alarm, obviously to delay a voteon a contested funding bill. Though Bowman denied attempting to delay the vote, his explanation for pulling the alarm was idiotic. Though his conduct was intended to delay the execution of a law of the United States by force, no sober person would argue that Congressman Bowman is guilty of sedition or that his actions are analogous to treason. This is why Congressman Bowman pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and won’t be facing 33 years in prison. It’s hard not to notice that Bowman is a far-left Democrat, the opposite of Tarrio and the Proud Boys.

The Supreme Triumph

Federal sentencing guidelines, which are issued by the United States Sentencing Commission, are notoriously complicated. The outcome of a guidelines analysis is a recommended sentencing range, which depends upon the defendant’s “total offense level” and “criminal history,” that is presented in months. To calculate the total offense level, a “base offense level is determined” and then points are added for aggravating factors including whether the offense involved the use of explosives, property damage, risk of harm to people, and hundreds of others. The criminal history of the defendant is factored into determining the “guideline range” of recommended sentencing.

Had Tarrio been offered a plea to the least serious charge in the indictment, he would have faced 27 to 33 months in prison. Functionally, this was the approach DOJ used for Mattis and Rahman.

But prosecutors looked to enhance Tarrio’s sentence because the offense involved destruction of property, the offense interfered with the administration of justice, the offense involved “extensive planning,” Tarrio held a “leadership role,” and Tarrio obstructed justice. These enhancements increased Tarrio’s offense level to the point that corresponds to 151 to 188 months’ imprisonment.

If those enhancements were questionable, the decision to apply the terrorism enhancement shows a government possessed of political bloodlust. On August 17, 2023, the government filed its sentencing memorandum in which it argued that the Proud Boys’ conduct was a “federal crime of terrorism.”

For the terrorism enhancement to apply, the guidelines impose two requirements. First, the offense must have been “calculated to influence…the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion”; second, it must be an offense enumerated in 18 USC § 2332. Proving the first element was no sure thing—indeed, the United States Probation Office concluded that the terrorism enhancement did not apply. Yet the government took nine pages of its sentencing memorandum and six more pages in a supplemental filing to make the case that it did. On the other hand, it took only two sentences to meet the second requirement:

Count Six, on which all defendants were convicted, and Count Seven, on which Pezzola was convicted, charged felony Destruction of Government Property in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1361. This offense is listed in 18 U.S.C. § 2332b(g)(5)(B)(i). (Italics my own.)

Count six alleged that the defendants damaged “a black metal fence,” and count seven alleged that they damaged a window. In short, the government could only argue—and did argue—that the Proud Boys’ conduct constituted a “federal crime of terrorism” because Tarrio’s co-conspirators “tore down the fence on Capitol grounds” and one of them “smash[ed] the Capitol building window.” And, of course, Tarrio did neither of those things since he was not in Washington on January 6. This seeming triviality more than doubled Tarrio’s exposure to 30 years to life. On top of that, to exceed the 20-year statutory maximum on the charge of seditious conspiracy, DOJ argued for consecutive sentences, which is rare.

As with the overcharging analysis above, some may think that the literal application of this rule should be the end of the inquiry—that no prosecutorial discretion should be used. But that is naïve. At this stage in our overregulated nation, only the tattered remains of prosecutorial discretion stand between any citizen and a federal indictment. Countless Americans are technically guilty of obscure federal offenses that some calm and dispassionate prosecutor chose not to charge precisely because the conduct, though meeting the technical elements of the offense, didn’t meet its purpose.

At any rate, the department is exercising discretion—it’s just doing so based upon the results of a political litmus test.

For Mattis and Rahman, the United States Probation Office filed a presentence report in which it concluded that the terrorism enhancement applies to both defendants. This conclusion was obvious: the defendants threw a Molotov cocktail into a police vehicle. DOJ should have advanced that argument strenuously. It didn’t. Instead, the government used its discretion to dismiss a seven-count indictment with a 30-year mandatory minimum sentence and rescind the defendants’ guilty pleas (with their enthusiastic consent, no doubt). Next, it agreed with defense lawyers to recharge the defendants with a single, lesser offense that had a five-year maximum sentence. It did all this for the purpose of avoidingthe terrorism enhancement and thus a crushingly harsh sentence for left-wing defendants.

In the Proud Boys matter, however, the government did the opposite. Probation determined the enhancement didn’t apply, yet DOJ prosecutors argued preposterously that it did.

To explain its uniquely harsh position, the Department argued that “any disparity between these defendants and others…is fully warranted based on the defendants’ conspiracy and conduct.” This is begging the question: the whole purpose of the sentencing guidelines is to adjust the offense level based upon an objective evaluation of conduct. Federal prosecutors were shoehorning their personal political outrage into an argument for a higher sentence, as shown by their belief that Tarrio’s conduct was “among the most serious that a democratic nation may face—a breakdown of constitutional order and the rule of law.” In other words, the man who wasn’t in Washington D.C. on January 6 because he had the scruples to comply with a court order requiring him to leave the city also intended to subvert the entire “constitutional order and the rule of law.”

The Thing Speaks for Itself

The disparity in treatment reflects the supreme triumph of form over substance: left-wing defendants threw a burning Molotov cocktail into a police vehicle after threatening to burn police stations and courts. Everybody recognizes that as terrorism. But a sympathetic DOJ responded by downgrading the charged felonies to sidestep the terrorism enhancement. It then argued for a year-and-a-half in prison. The right-wing defendants, conversely, damaged one fence and broke one window, conduct not generally understood as terrorism. And yet the government tried to imprison them for more than three decades! As of this writing, the government’s appeal is pending.

For Tarrio and the Proud Boys, the Department of Justice relied on abstruse and technical definitions (“terrorism”) and contorted reasoning in charging the case and determining the ultimate sentence. In the case of Mattis and Rahman, it did the same thing—ignoring the plain meaning of words and statutes—but to reach a shockingly lenient sentence.

If the first half of this story suggested that the Department’s integrity has been compromised by politics, the second half proves it. As they say in the law, res ipsa loquitur.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

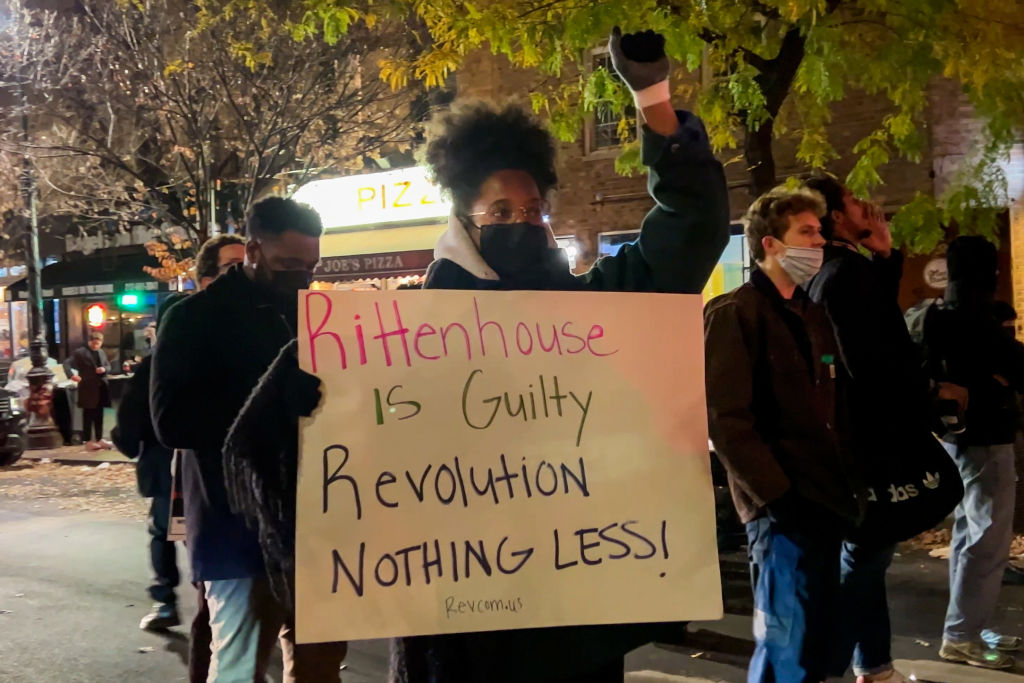

The aftermath of the Rittenhouse trial exposes a bitter divide across the nation.

The queering of the American frontier.

Patriot Front may not technically be staffed by FBI agents, but the effect is the same.