We knew it all along that Officer Chauvin did not murder George Floyd.

A Tale of Two Crimes, Part I

The Justice Department’s blatant politicization of the law.

This is part one of a two-part essay that examines the politicized nature of the Department of Justice.

Colinford Mattis went to Princeton University; Urooj Rahman went to Fordham. They earned their law degrees from NYU in 2018 and 2019, respectively, by which time they were saturated in the combustible self-righteousness of left-wing politics.

A spark arrived on May 30, 2020, when the George Floyd riots reached New York. Mattis and Rahman were angry: Rahman recorded herself opining that “all the police stations” and “probably all the courts” need to be burned down and “the only way they hear us is through violence.” She never defined “they” and never explained why she and Mattis were appropriate messengers. Their message was never particularly clear, though the “raised fist” T-shirt depicted in Rahman’s mugshot tells you what you need to know.

What was clear, however, was that Mattis and Rahman were bent on destroying a symbol of law and order. Around 1 a.m., Mattis drove a minivan toward an NYPD precinct in Brooklyn while Rahman sat in the passenger seat, armed with two Molotov cocktails. As they approached, Mattis parked the van, and Rahman exited the passenger side, ignited the incendiary, and threw the burning concoction through the window of a parked police van in the vicinity of other rioters. They fled but were arrested shortly thereafter. Police found another Molotov cocktail and precursor materials, indicating that Mattis and Rahman planned to do it again.

They were charged in a seven-count indictment. When charges were filed, a senior FBI official promised that “the consequences for conducting this alleged attack…will be severe.” Simultaneously, the NYPD’s police commissioner was “confident that the severest penalties under the law [would] be sought.” These claims were justified—one count of the indictment carried a 30-year minimum sentence.

But it never happened. Instead, Mattis and Rahman were sentenced to 12 and 15 months’ imprisonment respectively. How did this happen?

The facts show that in 2022 a Biden-appointed United States Attorney derailed the pending sentencing hearings, dismissed the indictment against both defendants, reneged on plea agreements already accepted by the court, and reversed the government’s plan to argue for severe sentences. All of this violated official policy in the “Justice Manual,” which spells out in detail the policies and procedures that the Department of Justice follows in prosecuting cases. The conclusion is inescapable that the Justice Department applied an ideological litmus test to Rahman and Mattis. Their crimes were committed in the crucible of a nationwide left-wing conflagration stemming from the putative murder of George Floyd. That is, while Mattis and Rahman are terrorists, their terrorism was in service of the Left’s 2020 favored cause—the so-called “Summer of Floyd.” Other prosecutions at the time revealed a similar bias.

Initially, the government’s resolve was apparent. Mattis and Rahman were indicted and arraigned in June 2020. At the government’s request, a detention hearing was held, which are common in matters involving defendants who pose a risk of violence or flight; filings show the government was convinced Mattis and Rahman were both. Notwithstanding the government’s position, the magistrate released both defendants on bond, and the government appealed.

On appeal to District Court Judge Margo Kitsy Brodie, Assistant U.S. Attorney Ian Richardson argued:

These two defendants weren’t just throwing firebombs at the police themselves, they were inciting other violence by offering fire bombs to other people in the street. They had multiple fire bombs that they were offering and they had components to create others and to ignite them…. I think the thing that bears repeating here is that these aren’t people with nothing to lose. They come from privileged backgrounds…and they were willing to throw that all away.

The government’s detention memorandum reveals its resolve: “The defendant’s criminal conduct was extraordinarily serious.” But Judge Brodie denied the government’s appeal from the bench—meaning she had already made up her mind when she entered the courtroom.

The government appealed that decision to the district court, where the government lost again. In almost every detention proceeding, this would be the end of the matter. But this was not the end of the matter.

The government appealed that decision to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, where, on July 7, 2020, it lost in a 2-1 decision. If appealing to the District Court demonstrates the firmness of the government’s conviction, appealing to the Second Circuit puts an extreme emphasis on it—any such appeal would have required the solicitor general’s approval. This shows that at the outset of the case the prosecution was convinced that Rahman and Mattis “present[ed] both a severe and ongoing danger to the community and a serious risk of flight if released on bond” and that “[t]he evidence against them [was] extremely strong.” Although the government lost the detention issue, it had a firm conviction that its case was just.

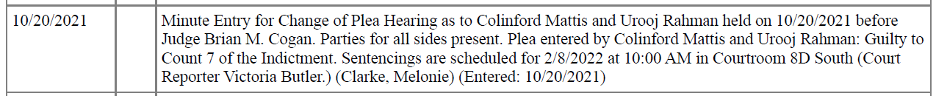

The docket reveals that the next 12 months unfolded as experienced attorneys would expect. The government provided plea offers to the defendants by February 22, 2021, and negotiations continued in the spring and summer. On September 23, 2021, the assistant U.S. attorneys notified the court that “the defendants…will accept the government’s plea offer” and requested that the court “schedule an in-person change of plea hearing at the earliest available opportunity.” On October 20, 2021, the defendants pleaded guilty. Most of this was routine, though the fact that the plea agreements were not filed publicly (then or now) is suspicious. Indeed, you would not have known to which offense the defendants had pleaded unless you were physically in court (unlikely, given widespread COVID concerns prevalent in October 2021) or were paying attention to the “minute entry” on the docket. Here’s what it says:

“Guilty to Count 7 of the Indictment.” Though punishable by up to ten years’ imprisonment, count seven (possessing an explosive device) was still among the least serious charges in the indictment.

By comparison, counts one and two (use of explosives and arson) require a mandatory minimum sentence of five years and up to 20 years. Count three (using an explosive to commit a felony) has a statutory maximum of ten years’ imprisonment, which must be served consecutively to the punishment for counts one and two. Count four (conspiracy to commit arson) also has a statutory maximum of 20 years. And, above all, count five (use of a destructive device) provides for a mandatory minimum of 30 years in prison! In the context of crimes that prosecutors had earlier characterized as “extremely serious” and substantiated by “overwhelming evidence,” this plea agreement was generous. It likely reflected the outcome of what the New York Times described at the time as “tense debates over weighty charges brought against protesters” within the U.S. Attorney’s Office. At any rate, a later filing showed that the government intended to request “a sentence at the statutory maximum of 120 months’ [10 years] imprisonment” and that the “defendants stipulated” that this was an accurate assessment of their exposure.

Then everything changed.

On October 15, 2021, Breon Peace was confirmed as Biden’s pick for United States Attorney for the Eastern District of New York. As the new U.S. attorney, it would have taken months for Peace to get up to speed on general office practices, let alone specific cases. As such, Peace was probably unaware that in December 2021, prosecutors argued that Mattis and Rahman faced a “substantial sentence” of “120 months.” In other words, the U.S. attorneys still believed the case would resolve with a ten-year sentence—not the grand slam a crime-weary New York public might want but close enough to “severe consequences” to credibly deliver on the big words of the June 2020 press release.

But Peace was up to speed by May 10, 2022, when prosecutors filed a notice unlike anything I’ve ever seen. In it, they wrote: “The government…submits this letter to…notify the Court that the parties have reached an alternative resolution of the charges in this case.” This is bizarre, since the matter had already been “resolved” when the defendants pleaded guilty seven months earlier. The bizarreness only grows. Later in the filing, the government explains its reasoning: it wanted to argue for a lower sentence because it had:

recognized, based on the nature and circumstances of the offense and the histories and personal characteristics of these defendants, that, regardless of the applicable Guidelines range, it would be appropriate to sentence these defendants to terms of imprisonment far below the applicable Guidelines sentence.

Recall that the “nature and circumstances” of the offense were that Mattis and Rahman threw a Molotov cocktail into a police vehicle, solicited others to do the same, and were prepared to do it again before they were caught. The “histories and personal characteristics of these defendants” include that they attended elite colleges and the same elite law school as Breon Peace, bastions of radical left-wing politics. At the beginning of the case, the prosecution used this same reasoning to argue for pre-trial detention and later to ink plea agreements to ten-year sentences. But, under Peace, the government repurposed that reasoning to argue that the defendants’ “advanced degrees” were “highly significant mitigating factors” and to strike new plea agreements pursuant to which the government “agreed to recommend a non-Guidelines sentence of 18 to 24 months’ imprisonment.”

To accomplish this, the government needed the court to retract the guilty pleas, dismiss the indictment, let the government file a new charge with a trivial offense, let the defendants plead guilty to that new offense, and then allow the government to argue against itself for a sentence in the range of 18 to 24 months. In the following months, that is exactly what transpired.

The government’s December 2022 sentencing memorandum serves as something of a capstone on this farce. It begins with an encomium on the George Floyd riots. It ends by arguing that a sentence in the range of 18 to 24 months is “broadly consistent with similar sentences imposed for similar offense conduct committed during civil disorder.” To support this claim, the government cites federal cases in Minnesota and two in Washington (1, 2) involving defendants who were sentenced to 20 to 48 months imprisonment for arson offenses. Every cited case involved defendants who committed violent felonies in furtherance of left-wing rioting during the Summer of Floyd, further revealing the Justice Department’s political biases.

It’s rare for the government to dismiss an indictment prior to case resolution; even rarer when supported by “overwhelming evidence.” But, barring instances of prosecutorial misconduct, I have never heard of the government dismissing a strong indictment after a defendant has pleaded guilty so that the government can file a lesser charge and argue for a trivial sentence. Ever.

Though we may never know who orchestrated this farce, we do know that Justice Manual section 9-27.400 requires that “federal prosecutors may drop readily provable charges [only] with the specific approval of the United States Attorney.” The jaw-dropping decision to dismiss earlier guilty pleas and replace them with a slap on the wrist required Breon Peace’s approval.

And all of it violated official policy. Justice Manual section 9-27.430 provides that “[i]f a prosecution is to be concluded pursuant to a plea agreement, the defendant should be required to plead to…the most serious readily provable offense.” In count five, Mattis and Rahman were charged with use of a destructive device. Federal law requires that a conviction for that offense be punished by not less than 30 years in prison, making it the most serious charge. Since the government had “overwhelming evidence,” the initial plea agreements “should” have required the defendants to plead to count five.

Instead, the government cut deals with the left-wing activists and inked pleas to count seven. In that fashion, 30 years became ten. Then Breon Peace became the U.S. Attorney. Thereafter, the government “recognized” that a lesser sentence would be appropriate, and ten years became two. Finally, the government filed its sentencing motion in which it all but apologized for prosecuting Mattis and Rahman, and two years became 15 and 12 months respectively. To explain this outcome, the government cited numerous examples when it slapped the wrists of violent left-wing terrorists, implying that its biases are justified because they are chronic.

During the “Summer of Floyd,” Mattis and Rahman gambled that the consequences for violent terrorism would be insignificant if perpetrated in the name of left-wing causes. Their gamble paid off, as the government’s initial enthusiasm for “severe consequences” stalled in the face of the growing weaponization of the Justice Department by political activists. In this fashion, de facto immunity has become the prerogative of violent left-wing terrorists, especially those who attend elite schools. In part two, however, we’ll see how Enrique Tarrio’s right-wing politics doomed him to the opposite fate.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Merrick Garland’s placidity disguises evil within.

Don't believe your lying eyes.

Serf's up.

Why can’t Democrat leaders see what we all see?

The Current Thing is an opportunity for courage.