Only by resisting the invasion of the spiritual kingdom by the temporal can digital despotism be condemned.

The Wonderful Life

Feel-good platitudes aren’t enough to sustain a healthy society.

This year a handful of my students were forced to watch Frank Capra’s 1947 classic It’s a Wonderful Life. Their reaction was: that’s bulls**t.

“So life is wonderful because you have a family and friends, and God sends guardian angels to watch over us?” exclaimed one of them. For my part, I do believe that life is wonderful. I even agree with the film’s conclusion that it is a gift. But not exactly for the reasons Capra presents to us. In fact, if the promises of meaning presented in the film were the only ones available to me, I would be clamoring along with my students about life’s emptiness.

George Bailey, the film’s protagonist, is an exemplar of the post-war bourgeois lifestyle. Comfortably middle class in his socioeconomic status—as well as in his moral, aesthetic, and existential sensibilities—his character embodies the “Middle of the Road.” He was not one of the corrupt wealthy elites, like the villainous Mr. Potter, nor was he poor like Annie, the stereotypically sassy maid (the film’s one black character).

Bailey’s life revolves around the dynamic of the atomized suburban nuclear family. His sense of fun comes across as tame. He tears up the floor at the school dance during the Charleston competition and flirts with his love interest while walking her home. Bailey’s persona is juxtaposed against the overtly ethnic flair of the Martini’s, an immigrant family whom Bailey has helped to achieve the American Dream. The pro-assimilationist tone with which the Martini’s are portrayed speaks to Capra’s quickness to shake off his own southern Italian roots in favor of adopting—and in his films, glorifying—the prim and proper WASP aesthetic.

His religious proclivities are a forerunner to Moral Therapeutic Deism: he prays to God in moments of need, but really his claim to heavenly favor is that he is a “respectable person.” This ethos can only carry weight because, at the time of the film, sentimental attachments to vestiges of an antiquated cosmology like angels and miraculous signs still held some cultural currency. This brand of religiosity is an example of what philosopher Charles Taylor identified as the post-Enlightenment ideal of “benevolence,” which served as a sort of “surrogate” form of agape or Christian love.

Benevolence derives from Christian moral values like selflessness, serving one’s family and community, and helping those in need. But unlike the Christian understanding of love, benevolence is the product of the individual’s autonomous force of will. Altruism comes to replace the specifically theological virtue of charity.

This optimistic view of individual will downplays the sense of depravity brought on by original sin and the subsequent dependence on the intervention of God’s grace through communal ties and the sacraments. The order of the cosmos, while it should have some level of regard for certain religious principles, is largely set by us humans’ free will and is disenchanted, losing the sense that its intrinsic design is set into place by, and is a sign of, the Creator.

Benevolence is agape minus communion…out go the ties of dependence on God and community. We may “respect” God and neighbor, but by no means is our atomized existence ontologically intertwined with theirs. Christmas, once the celebration of incarnational mysteries too deep to fathom, is reduced to sentimental, moralistic trappings.

This rejection of the “sources” of humanistic values, claims Irish journalist John Waters, is “deeply damaging to our children’s chances of peace and happiness.” Speaking specifically about the form of “post-Catholic” spirituality that has emerged in Ireland over the last few decades, Waters concedes that “it may be possible for an individual to live a hopeful, meaningful and free life without God” or with a therapeutic view of Him. But “there is no evidence,” he argues, “to suggest that this can be achieved by a society. And the irony is that the ‘hope’ atheists claim to feel may well derive not from their own philosophical resting place but from the background radiation of hope deriving from the residual effects of intense cultural faith.”

Those who “piggyback” off the few who maintain their ties to the ultimate Source of hope run the risk of taking for granted that said hope “always existed and will remain in spite of it all,” which is a “folly akin to sawing away the branch we are sitting on.” As the society as a whole continues to sever these ties, the remaining “buffers” will eventually wear away, leaving us “doomed to a form of collective depression.”

Capra leaves us with the message that “no man is a failure who has friends.” In the midst of financial instability, marital conflict, political corruption, and our individual moral failings, we need not despair. Nor need we turn to money, pleasure, or power. All we need is to look around at all the people whose lives we have touched. But what is it that sustains the possibility of real, meaningful, and lasting connections with our fellow human beings in light of our and others’ limitations (and inevitable mortality)? What some call Capra’s “fantasy of goodwill” leaves us without answers to these foundational questions.

We are now past the point where we can pretend that post-Christian trappings make for plausible Christianity. Frank Capra’s easy assumptions and borrowed symbols no longer carry persuasion. The relativistic and sometimes nihilistic air of postmodernism that young people breathe in might be disheartening, but in the least, it’s refreshingly honest. They are right to toss out the claim that in themselves these realities are enough to “save” us.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

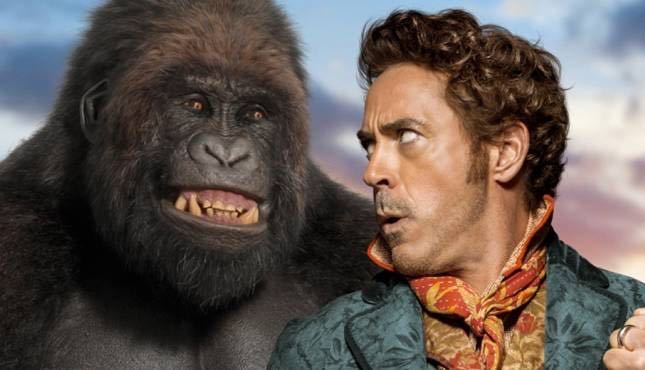

Robert Downey Jr.’s failures in Doolittle are the failures of American film today.

The Bible, the ballot, the border.

The Apollo 8 astronauts worshipped God while circling the moon.

Thanksgiving is a window into our country’s religious heritage.

What we can learn from recent celebrity conversions.