Democracy and despotism in a digital age.

The Monuments of Our Republic

As the statues go, so goes the citizenry

Since May of this year, over 290 monuments have been destroyed, defaced, or removed from America’s increasingly vacant public spaces. Considerable ink has been “spilled” over the diseased political psychology behind these attacks on some of America’s most enduring “bodies.” Very little, however, has been written to remind us why public monuments matter to our republican liberty. What is the damage done to our civic lives when the public square gets denuded by force and fraud?

For the engaged citizen, America’s best public monuments do not promote cheap patriotism or portray simple-minded celebrations of America’s untainted history. On the contrary, they cultivate an aesthetic taste critical to our lives as citizens of a republic. They shape a political imagination that allows us to envision the public good, affirm belief in our deepest principles, confront the shortcomings of our past, and grapple with the limitations to our efforts to secure political justice. In short, America’s public monuments instill civic pride and courage, as well as prudence, humility, and self-limitation.

Such public art is especially necessary in a community dedicated to the kind of abstract principles laid out in our Declaration of Independence and preserved by our Constitution. For while the foundational core of our regime may be appreciated by reason alone, our passionate attachment to liberty and equality, to individual rights, and to the well-being of our fellow citizens requires visible and tangible instantiations.

The universal ideas and ideals on which America is based are embodied, fought for, challenged, and preserved by particular human beings who often sacrificed life and limb in the service of such ends. The prominent public placement of such examples, captured in stone and steel, marble and bronze, compels us to confront the human meaning of our political principles and the human costs associated with realizing them.

The Vietnam Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. illustrates this perfectly. No one would think that Maya Lin’s granite monument, a black scar bearing the names of nearly sixty thousand American dead as it carves through nearly two acres of earth, “celebrates” the war in some blithe or naïve sense. And yet the very power produced by its size and its sea of names overwhelms the viewer and leads him or her to focus more on abstract ideas than on the particular humans whose deaths are being commemorated.

The addition of the Three Soldiers and the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, both created by different artists and erected at different times, draws the viewer’s attention back to the human costs endured by the individual men and women—white, black, and Latino—who fought and died on behalf of their country. Taken as a whole, these three memorials form an installation which demands that we continue interrogating the war’s justice even as it highlights the noble sacrifice of a diverse citizen body who answered the call of their republic. What is this if not the hallmark of a free people?

Liberty and Art

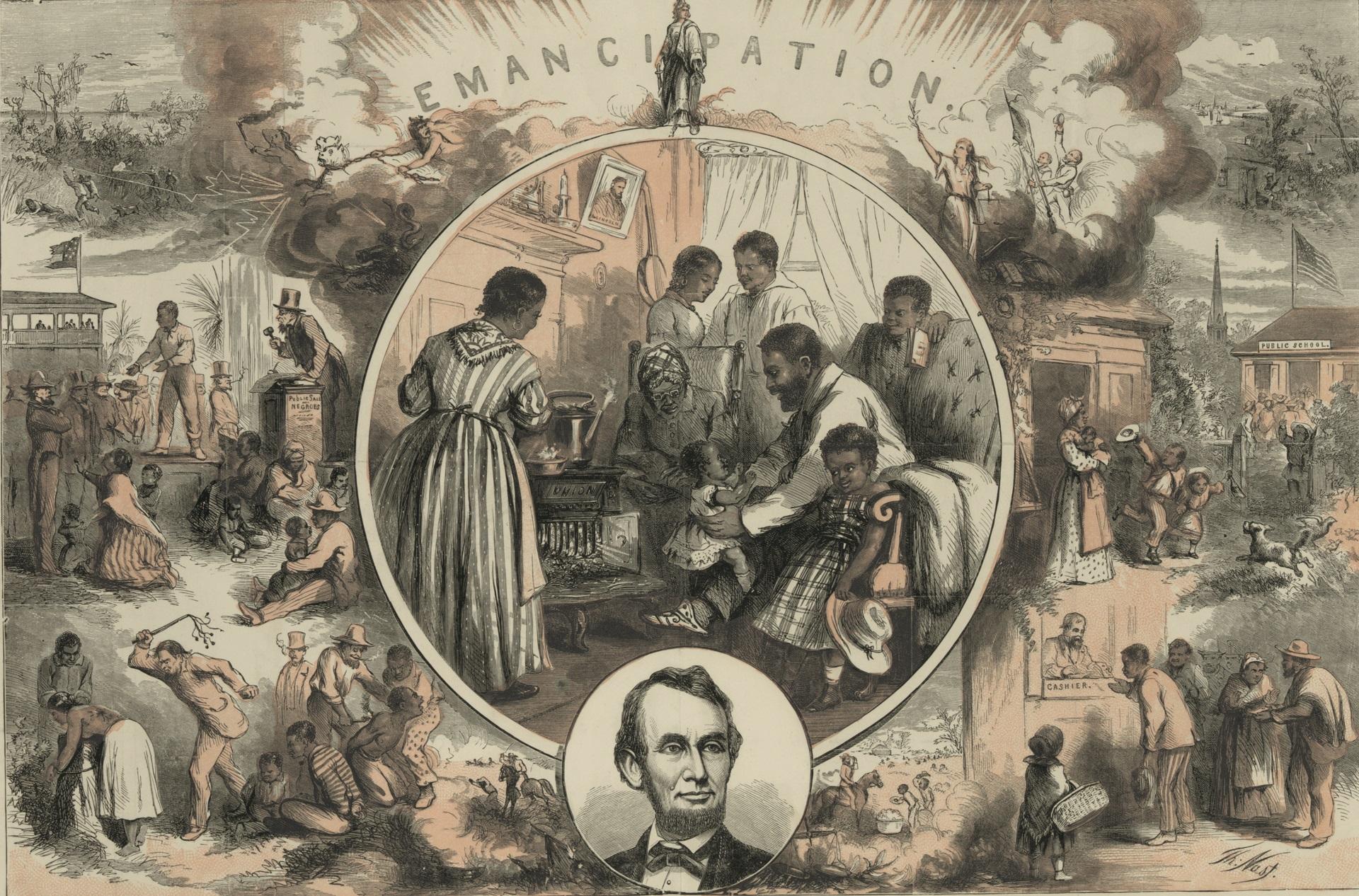

Those protesting on behalf of BLM or Antifa haven’t targeted this monument (yet). But many of their targets produce similar salutary political effects. This is especially the case with the copy of a monument deemed so offensive that public officials in Boston, blinkered by progressive wokesterism, rushed to remove it from its innocuous setting before it could excite violence. Without masking the inhumanity of slavery, the Freedman’s Memorial captures a glorious moment in our nation’s history while testifying to the power of a slave whose rising (not kneeling!) body, when upright, looks as if it will stand even with a Lincoln made shorter for perhaps this very purpose.

The citizen viewing this monument should take pride in our country’s dedication to natural rights even as she is reminded that the effort to secure justice for all remains woefully incomplete. Such, at any rate, was the judgment of Frederick Douglass who, in the days after speaking at the statue’s dedication, acknowledged in the National Republican the monument’s virtues and vices while calling for additional monuments to complete the story of freed slaves’ enfranchisement under President Grant.

By capturing human differences and imperfections, situating them in different times and places, our republican artwork prompts us to think about the contexts in which diverse human beings act on behalf of the common good. It thus differs from the fascist art of Mussolini’s Foro Italico or Quadratto Colisseo, which idealizes the human form and situates it in a realm beyond politics. Our monuments remind us that our liberty is secured by different and often competing segments of American society, working together toward the realization of our political principles under widely divergent circumstances. Such monuments both portray and cultivate civic prudence in citizens.

It is true that individuals remembered for their great virtues often have great vices. But the realization that the “line between good and evil runs through every human heart” shouldn’t lessen the virtue of their achievements or lead us to reject their example; it should moderate us and what we can hope for from the most talented among us.

Even monuments to injustice, like the Confederacy, can be made to serve important republican functions. They remind us that even within our republic individuals may arise who, animated by rival conceptions of liberty, are willing to oppress and enslave their fellow citizens to realize their ambitions. Were we to place such statues in their proper context rather than simply tearing them down—as citizens of Bolzano, Italy did with their fascist art—we could transform misguided heroism into a cautionary tale about the fragility of our republic.

If we accept the premise of today’s progressivism that newly emergent moralities can erase any aspect of our history, we potentially doom all public art. Without physical embodiments of America’s triumphs and tragedies, we lose the ability to think in meaningful terms about the human significance of our regime and the perpetual struggle to fulfill its promise.

In that case our public art will become like that of the E.U., whose uninspiring abstractions are perfectly unobjectionable to their multi-national community. But these are boring, devoid of humanity, and divorced from politics, reflecting a political body unable and unwilling to define itself, its borders, and its members. This is an example all Americans of taste and sense should avoid.

At a time when citizens, anxious to protect themselves, increasingly withdraw from public space, it is critical that those unique embodiments of our res publica, its liberty, and its diversity, remain in the public square. They are the only bodies immune to the threats faced by human flesh. But even these bodies need defense. For their burnished bronze and polished marble are not immune to that other, deadlier virus destroying America’s political body from within.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Revisionist Black supremacist history can't grasp our shared equality.

There is nothing manly in throwing up your hands.

They are as clueless as the ancien régime.