How to defend the Republic against the Deep State.

The Leviathan’s Democrats

To defeat bad ideas, defeat their believers.

It’s a stubborn historical fact that democratically elected Western conservative administrations in the Anglo-American political tradition have presided over the erosion of almost everything that conservatism purports to revere. Soul-searching over this calamity would need to include a painful re-appraisal of the ’80s, when things seemed to be going well for conservatives, with Ronald Reagan’s victories in 1980 and 1984 and Margaret Thatcher’s in 1983 and 1987. This was the decade of the conservative reawakening, of leaders winning over electorates with their simple faith that “the facts of life are conservative” and a determination to roll back the quasi-Socialist mentality of the sixties and seventies.

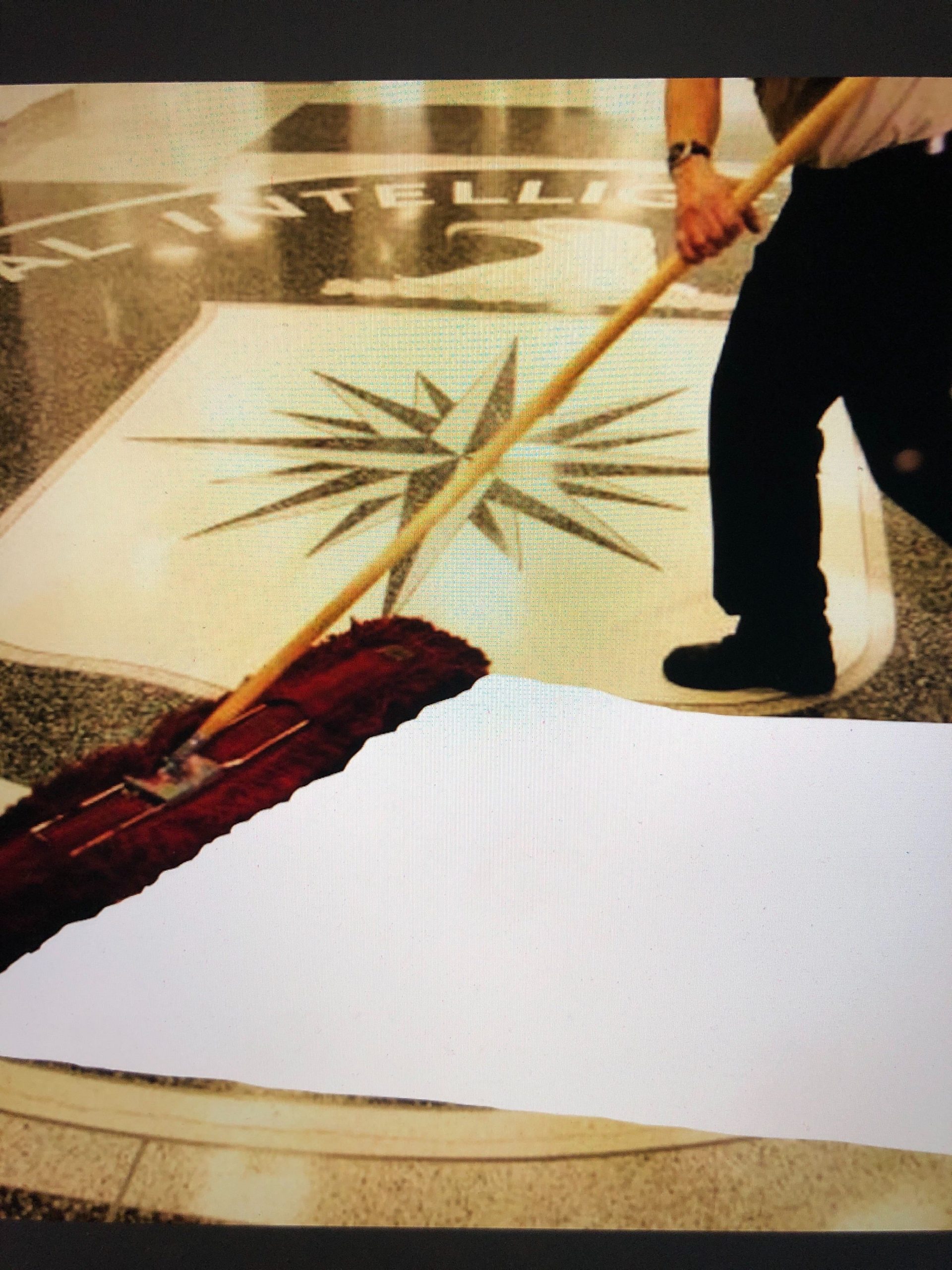

Large electoral mandates can however seduce both politicians and publics into a naïve overestimation of their part in the real exercise of power, and a tragic underestimation of the intractable nature of government bureaucracies and other powerful civil institutions. There was a wilful blindness—in nations across the Western world—to the growth of an overwhelmingly left-leaning professional/managerial/bureaucratic class (now derided as The Blob and identified with the administrative state) with agendas often at odds with any conservative administrations they may theoretically serve. This “deep state” is never up for election but controls the engines of power. The 2016 presidential election was the moment when alarm bells really started to sound for elected conservative politicians, who had, for too long, been blindsided by this progressive juggernaut.

Unsurprisingly, neither civil service bureaucracies nor the non-profit sector have ever kept statistics on the political leanings of their employees. But there are clues. Research in the U.S. finds that “the political beliefs of the median federal government employee lie to the left not only of the median Republican, but also the median Democrat”. In the U.K., Unherd columnist Peter Franklin, reflecting on his own experience working in two government departments, asks “how many of the civil servants that most closely serve this Conservative government are actually left-wing? Well…I would say approximately all of them.”

Eighties conservatives made a great error in failing to take much interest in the political complexion of the civil administration that would remain after it had been shrunk and starved into submission. Establishing a “small state” is not, in any case, a realizable goal in a modern post-industrial complex society. In reality, the despised nanny state grew throughout both the Reagan and Thatcher regimes, despite a favorable electoral climate and all the passionate rhetoric—Reagan’s “government is the problem” and Thatcher’s “roll back the frontiers of the state.” We underestimated the staying power of the bureaucratic leviathan. We should have paid more attention to Robert Conquest’s apocryphal third law of politics: “Any organisation not explicitly right-wing will sooner or later become left-wing.”

Long before the ’80s it had become obvious to conservative intellectuals that there was a worm in the apple of pluralist democracy: the leftist sheep-dip of university humanities courses. Civil administrators are overwhelmingly drawn from these humanities backgrounds. In this way the ideals of pluralist politics have gradually been undermined by a politically mono-cultural permanent administrative class. Modern conservative politics has shied away from confronting this reality of always being up against (Franklin again) “a system that churns out a hostile graduate workforce from which the civil service is recruited.”

Leveraging large conservative electoral majorities to install future-proofing mechanisms to make civic institutions more fairly reflect the political composition of the democratic society they are supposed to serve would, of course, have presented many obstacles. Political interference in senior appointments to ostensibly independent public bodies, for example, would have sounded heavy-handed to conservatives striving to play fair. Another practical problem would have been attracting conservatives to apply for these positions in the first place.

The reaffirmation of free enterprise in the eighties did bear fruit. But even the tech revolution was and remains tied closely to the administrative state, and naïve expectations were dashed that private professionals could always be relied on to get that the facts of life are conservative. This was the thinking behind the wave of privatizations in the 1980s, the result of which was largely to puff up the same old public sector bureaucrat class with a sense of itself as “businesslike” with salaries to match. And contrary to the romantic vision of rugged individualist entrepreneurs with conservative instincts, the new titans of Silicon Valley have found that they can have it both ways; as billionaires in social justice warrior clothing.

As it dreamed of rolling back the corporate state, ’80s conservatism was setting itself up for a rude awakening: the relentless leftward drift in the political allegiance of the future “opinion-forming” elite, with consequences well beyond just an uncooperative civil service. Left-wing politics stopped being primarily a working-class struggle decades ago, but the left wing = poor and caring/right wing = rich and hard-hearted fallacy remains the intellectual matrix which frames the moral and political philosophy of Western liberalism. Far too many instinctive conservatives (and conservative politicians) still reflexively allow this fallacy to confuse their thinking.

It was a Republican president in 1961 who warned of subversions lurking within the corridors of democratic government when he coined the term military-industrial complex. How much more necessary it was 20 years later to beware a left-leaning academia-media complex and its power to promote or frustrate the agendas of elected politicians and determine the allowable in public discourse and to elevate and empower “activists.”

The academia-media complex is energized by a feedback loop between the overwhelmingly left-wing academy and the largely left-wing media, but its ‘woke’ progressive agendas originate mostly in the academy, increasingly divorced from the rough and risky business of capitalist wealth creation and the socially conservative instincts of ordinary citizen. Its game of competitive victimhood has ratcheted up ever more dubious “social justice” pseudo-pedagogies that have been eagerly embraced by the media and corporate advertising executives. Media bias is probably something that just has to be endured by any conservative administration, but countering bias in the education system is (and should always have been) a legitimate political goal.

The real appeal of leftism to the prosperous middle class is essentially narcissistic, offering a cheap way to feel sophisticated and virtuous. Millions of people recognise these truths—whether consciously or subconsciously—but saying them out loud is problematic because you are likely to be offending some of your friends, colleagues, and neighbors. Even combative “conviction” politicians flatter the electorate as a whole and keep targets of invective within careful limits. Because its policy program is constantly squashed by the left-wing leviathan, conservatism is ever less truly “in power” in our pluralist democratic system.

It should not have been beyond the imagination of 1980s conservatism to put in place mechanisms to prevent the incursion into the academy of revolutionary activists. But if and when the kind of electoral fair wind that existed in the ’80s comes around again, we must not fail again. Fighting an election on a policy of rooting out political bias amongst most teachers, most academics, most civil servants and most of the legal establishment would be one hell of a game—but perhaps the only game in town.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Is the leftist dream now within reach? If President Trump loses, we will find out.

To fight prejudice, get the bureaucrats out of power.