The prognosis for free speech in America promises marked improvement.

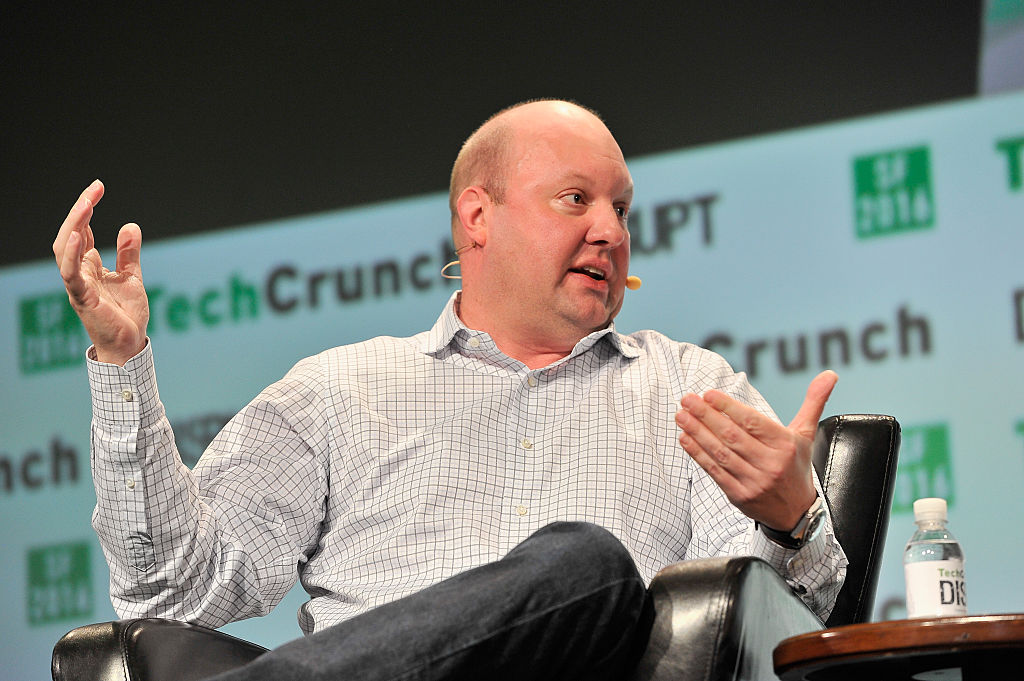

The False Promise of the Techno-Optimist

Marc Andreessen’s boosterism is naïve and unproductive.

With so many bad things happening in the world, it’s difficult to be optimistic. While wars in Israel and Ukraine grind on, leadership in Washington reaches new lows of incompetence and corruption, and the economy totters on the edge of decline. The future appears equally grim as populations age with no one to replace them, nations default on repaying their mushrooming debt, and the global order gradually disintegrates.

Fortunately, Marc Andreessen and some likeminded venture capitalists have a plan to fix this. Rather than dwell on the negative, he lays out an alternative vision that focuses on the positive. He maintains that for every problem, there is a solution, and that solution is technology. Just like it has done since the dawn of time, human innovation will continue to save humanity from itself and improve our quality of life.

At least, this seems to be the argument of Andreessen’s newest essay, “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” It glistens with pride, triumph, and good intentions. And it is written by a billionaire who helped design the first web browser and has grown fabulously wealthy investing in today’s newest technologies. If anyone can see the future and understand it, it would be Andreessen.

Unfortunately, for all Andreessen’s good intentions and financial successes, the manifesto’s many flaws render it unserious and counterproductive.

Andreessen makes obvious points about technology and progress, yet presents them as courageous and insightful. Of course, productivity, abundance, knowledge, and excellence are good things. Who says otherwise? According to Andreessen, it’s the ubiquitous but invisible enemy of mediocrities who espouse “statism, authoritarianism, collectivism, central planning, socialism,” along with “anti-merit, anti-ambition, anti-striving, anti-achievement, anti-greatness.” Even if one grants the generous assumption that such people exist, will this manifesto really change their mind?

Connected to this problem of arguing against an imaginary opponent, Andreessen betrays his lack of philosophical training through some slipshod reasoning. At no point in over 5,000 words does he specify what he means by “technology.” He mentions nuclear power and artificial intelligence on several occasions, but only to serve as his reason for “optimism.” He conveniently neglects some of the darker examples of advanced technology, like nuclear missiles, addictive computer apps, or carcinogenic processed food.

On a fundamental level, the term “technology” should pertain to all the products and ideas that result from human ingenuity. Because he doesn’t make this distinction, Andreessen speaks of technology as some kind of creative magic produced by the divinely chosen geniuses of humanity. Consequently, he bestows moral value on it and applies it to all life’s problems, material or spiritual: “We believe technology is liberatory. Liberatory of human potential. Liberatory of the human soul, the human spirit. Expanding what it can mean to be free, to be fulfilled, to be alive.” So, not only can technology be used to help with world hunger and producing cleaner energy, but it can also liberate, enlighten, and inspire the soul.

To be fair, technology can certainly help with meeting a person’s basic needs, and if those needs are met, that person can go on to do more creative and satisfying work. In this sense inventions like washing machines, automobiles, and the internet have freed up today’s population for other tasks. But can we really say that humanity today is more liberated, fulfilled, and creative because of this technology? Or is it more likely that we are more distracted, less fulfilled, and utterly unoriginal? This is the paradox that Andreessen ignores.

But philosophical incoherence aside, the manifesto’s other main flaw is that it perpetuates a myth about Silicon Valley that demands correction. Like many Americans, Andreessen and his colleagues believe that most of today’s innovation comes from the minds of plucky tinkerers in their garages acting on their big dreams. In a free market economy, investors give capital to these tinkerers who then create products that consumers want and rake in a hefty profit. This profit in turn allows the tinkerers to invest in more ideas and create more new products. Andreessen calls this “The Techno-Capital Machine”: “Human wants and needs are endless, and entrepreneurs continuously create new goods and services to satisfy those wants and needs, deploying unlimited numbers of people and machines in the process.”

But modern large-scale technological innovation is more complicated. As Wells King explains in his aptly titled essay, “Myth-busting Silicon Valley,” most of the technological innovations that people in the developed world enjoy were not the result of venture capitalists investing in a talented engineer with a new idea. Rather, the great technologies of the past century—the internet, the microchip, digital computing, satellites, nuclear power—were the result of government-funded research projects: “Only the federal government had the resources, perspective, and incentives to fund and coordinate academic and private-sector researchers as well as facilitate the initial application and commercialization of their discoveries.”

Most great revolutions in technology were not immediately profitable, and it would usually take decades for commercially-minded innovators to find any practical application for new inventions or theories. Without the federal government investing billions into military research labs to develop ARPANET, there would be no men like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, or Marc Andreessen developing popular devices and applications that makes people’s lives easier.

Acknowledging this doesn’t take away from the merit or creativity of these individuals; it just places them in the proper context. Realistically speaking, the kind of advancement Andreessen calls for in his manifesto will not come from enthusiastic venture capitalists trying to save humanity, but from more long-term investments from governments and more intellectual clarity from elite capitalists. What’s good for humanity is not always what people want, and what would help society progress is not always technological.

So does this criticism of “The Techno-Optimist” make me or others Techno-Pessimists? Not necessarily. Although the naïveté of Andreessen’s argument exposes the limits of technology, it doesn’t make technology an absolute evil. When used as a tool to facilitate productivity or creativity—i.e., as a means, not an end—technology is a key part of the modern human experience and can indeed remedy problems of global poverty and ignorance. When treated as the highest good in itself, technology will not only fall short, but also become misunderstood to such a degree that much desired advancement stops happening.

In truth, people today should become Techno-Skeptics, recognizing the value of technology without going overboard. As tempting as it is to believe we can innovate our way out of all of life’s problems and become like gods, we must humbly accept our humanity and deal with problems according to their nature. Only then will society fix its many problems and continue progressing once more.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

John Muir put human inventions aside to reap the benefits of nature.

The Left’s war on nature is integral to its larger project.

Dating apps exacerbate the crisis around forming long-lasting relationships.

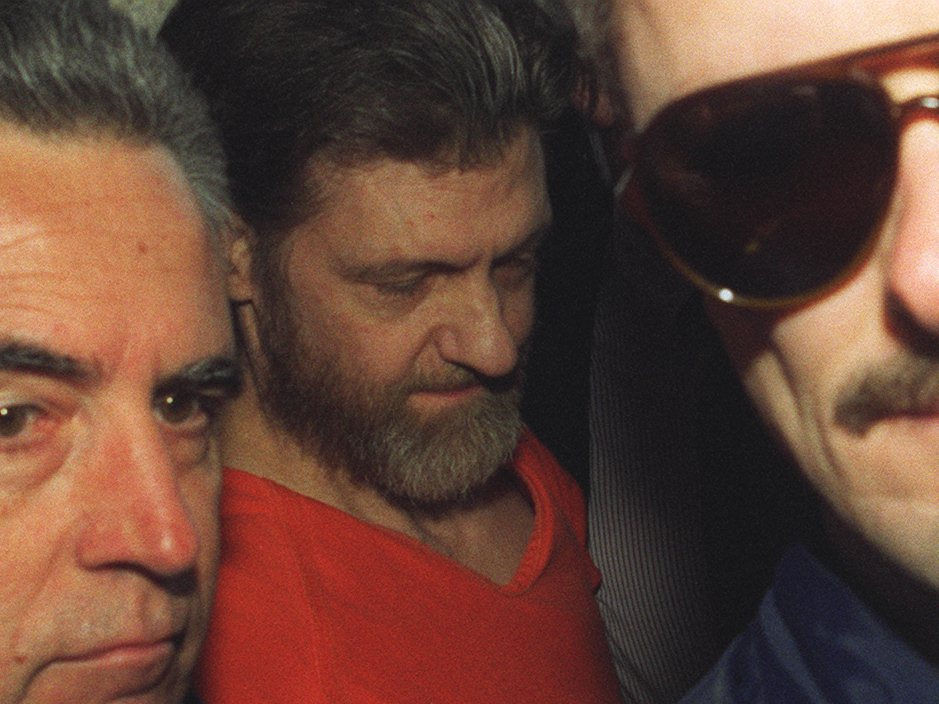

The Unabomber worshipped and rebelled against the false god of technology.

You don’t know the machine’s agenda.