The injustice of an inhuman religion

Cabin Fever

The Unabomber worshipped and rebelled against the false god of technology.

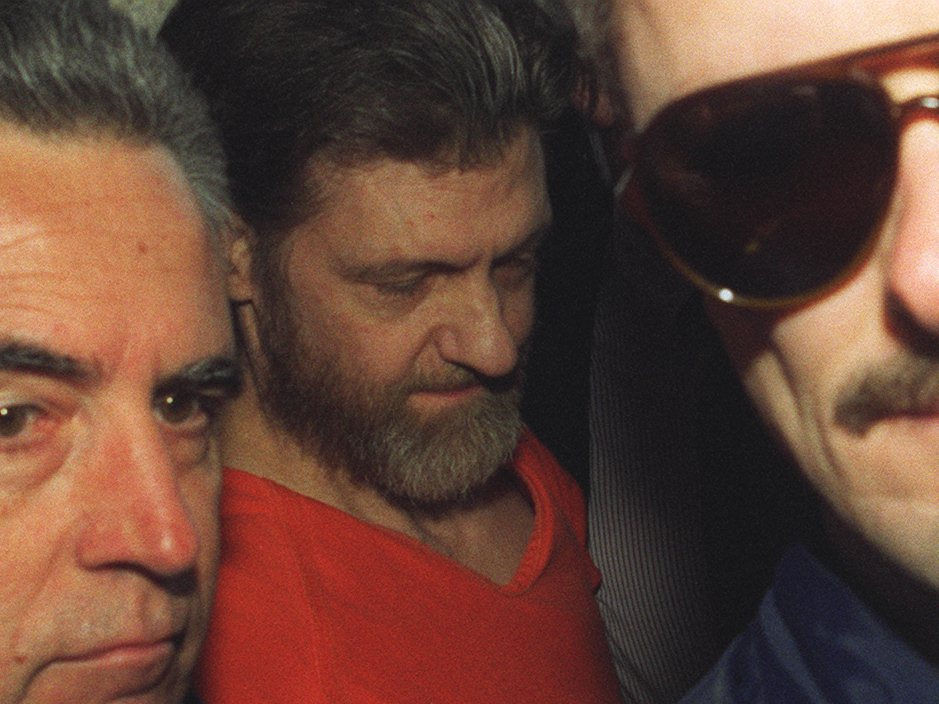

Theodore John Kaczynski, who died at his own hands in prison last week, was a devoted believer in science—until he wasn’t. “America’s most intellectual serial killer” abandoned a promising academic career to pursue a two-decade-long campaign of terror, murdering the Sacramento computer store owner Hugh Scrutton, advertising executive Thomas J. Mosser, and timber industry lobbyist Gilbert Brent Murray, and gravely wounding many others, including computer scientist David Gelernter. He wagered his notoriety to publish his Manifesto in the Washington Post, becoming a guru to green anarchists, a source of endless fascination to others, and ultimately offering the world the evidence of his identity.

Kaczynski was born on May 22, 1942 in a working class Polish American family in Chicago. According to a family story, he was hospitalized in isolation at nine months and came home a changed baby. What followed was the increasingly lonely childhood of a 167 IQ mathematics genius. He read college-level texts at ten, made ammonia bombs in high school, and, at 16, earned a scholarship to Harvard.

During his second year at Harvard, Professor Henry Murray recruited the eager teen for a psychology experiment. The 3-year-long ordeal, designed to measure reaction to psychological torture, was part of the CIA’s MK-Ultra program. It was, in Murray’s own words, “vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive.” Harvard dorm mates recall Kaczynski rocking while doing his homework. He made no friends and didn’t earn particularly high grades.

Harvard alumnus, and fellow lapsed academic, Alston Chase compellingly argued that it was at Harvard where the future Unabomber was made. In the post-World War II years, the Ivy League school adopted the General Education Curriculum that replaced moral education with positivist teachings that comforted students in the knowledge that science is a liberating force that will eventually yield a full understanding of nature. The optimist outlook was only challenged by a post-Hiroshima distrust of technology which Kaczynski eventually adopted. On top of it, the victimhood of the Murray experiment crystallized the grudges of his awkward childhood.

After Harvard, Kaczynski went on to graduate school at Ann Arbor, and then a professorship at Berkeley. Having developed a fantasy of living as a revolutionary agitator, the young mathematician, who took no part in the late sixties riotous Berkeley culture, quit his job and bought a cabin in the Montana wilderness.

Although there is ample evidence of him expressing interest in women, Kaczynski had few dates in his life. On rare occasions when he wasn’t rebuked, he sabotaged the relationship. As a teen, he broke up with a girl over her religious devotion, something that Kaczynski, being brought up by politically progressive lapsed Catholics, found exasperating. Or, as his brother David Kaczynski speculated, he fled an emotional connection.

Based in Montana, the former academic attended an Earth First summit, sabotaged logging equipment, and, in 1978, launched a campaign of terror. In the best tradition of sixties radicalism, he sent 16 bombs in 18 years, murdering three people and injuring 23. His first victims were acquaintances from Northwestern University, guilty of being insufficiently awed by the angry white man’s insights in sociology, and airlines which, in the bomber’s opinion, polluted the Earth. The FBI nicknamed him the “Unabomber”—universities and airline bomber. He later expanded his terror operations to the logging, computer, and advertising industries.

Kaczynski paused the bombings in 1987 after a woman spotted him planting a device, enabling the FBI to produce the iconic Unabomber sketch, sporting a hoodie and aviator sunglasses. The terrorist felt exposed at the time but resumed his campaign in 1993, inspired by al-Qaeda’s first World Trade Center bombing.

In 1995, Kaczynski offered to halt the violence if the New York Times and the Washington Post would publish his 35,000 word essay Industrial Society and Its Future. The work that became popularly known as The Unabomber Manifesto was run as a special supplement to the Post and immediately received accolades in the mainstream media.

The Manifesto asserted that industrialization has been a disaster to humanity, turning humanity into slaves who fill their days with meaningless “surrogate” activities. Because a peaceful return to nature was impossible, Kaczynski called to destabilize society, with the goal of fomenting a worldwide anti-industrial revolution.

I was an undergraduate at Berkeley at the time the Manifesto was published and can confirm it being read among students of all political leanings. The Unabomber didn’t tell us anything particularly revelatory—his ideas were already a part of the academic zeitgeist. In the nineties, Berkeley was broadly anti-Enlightenment, and the Unabomber put things in a way that was satisfying to read.

A true misanthrope, Kaczynski doled out hate evenly. His rejection of capitalist modernity pleased those on the Left, but being a radical, the mysterious author despised liberals and resented advancements they were able to make in a technologically advanced democratic society, from women’s rights to disability rights—which titillated the Right. He had nothing good to say about the liberal academia that rejected him:

University intellectuals constitute the most highly socialized segment of our society and also the most left-wing segment. The leftist of the oversocialized type tries to get off his psychological leash and assert his autonomy by rebelling. But usually he is not strong enough to rebel against the most basic values of society.

Passages like that resonated with the Gen Xer disgust for navel-gazing Boomer liberalism. I admired my peers’ willingness to consider ideas regardless of their source but found the whole treatise ridiculous. Kaczynski did not distinguish between free and unfree societies, because all were enslaved by technology, but, having lived in the Soviet Union, I knew that the differences were enormous and crucial. A few years prior to publication of the Manifesto, Communist regimes across Eastern Europe fell in a series of mostly bloodless “velvet” revolutions. If freedom triumphed peacefully, why is this man murdering people to solve what amounts to a side problem of alienation from nature? Moreover, it wasn’t just liberty that people wanted in Eastern Europe but all the trappings of capitalist modernity—air travel, answering machines, and the latest shade of lipstick.

Even during his Montana years, Kaczynski was a beneficiary of the most advanced civilization on the planet. His cabin was located not far from both an interstate highway and the town of Helena, Montana’s capital city. Helena had a library and a bookstore with a discounted collection of obscure sociology and political science books—try to find a remote town like that in Siberia! The highway connected the lone wolf with the world, allowing a quick way to deliver bombs should he decide to do so in person. The future terrorist celebrity developed admirable survivalist skills, but ultimately his lifestyle was financed by his aging parents, from whom he bummed a few thousand dollars each year.

Kaczynski offered no useful solution to the First World problem of “technology slavery.” His dream of a worldwide anti-technology revolution required a core dedicated minority that would keep the majority inculcated in a not-too-heavy-handed “nature” ideology while destabilizing the technologically advanced society at every opportunity. The anti-technology revolution, he predicted, would come everywhere at once. That’s somewhat analogous to Karl Marx’s prophecy of a worldwide proletarian revolution, starting with the most developed countries. Once it took place in the backward Russian Empire, its architects had to bend over backwards explaining what happened.

Kaczynski didn’t believe that a long march for nature is possible, but environmentalists of his generation accomplished just that. In less than a decade after the Manifesto saw the light, the man who was vice president of the United States during its publication released a film chock-full of images of sad polar bears and the Statue of Liberty submerged by the Atlantic. “Climate emergency” became the foundation of American science education, and the guiding light of policy. The policy is administered from above, with the enthusiastic support of Kaczynski-following “eco-anarchists.” Instead of liberation, it promises confinement in 15-minute cities guarded by facial recognition technology.

The Unabomber was not very different from other contemporary environmentalists in his hatred of logging. The logging industry suffered a profound setback when the Spotted Owl was placed on the endangered species list in the nineties. Kowtowing to special interests, California destroyed its logging industry, ensuring the now ubiquitous fire season during which people die almost every year. Aided by nefarious political interests, and mass market-nurtured hatred of modernity, Gavin Newsom killed more people in the name of nature than Ted Kaczynski.

The Berkeley students who read the Unabomber Manifesto graduated into the Dotcom boom. Kaczynski was right to single out computer technology as a qualitatively different force in the modern world. It produces mini-Kaczynskis, desexed and disconnected men, and creates an easily manipulated marketplace of ideas managed by corporate-government conglomerates. Social media monopolies now threaten to turn free societies into bastions of censorship. Having assumed control of online communication, the revolutionaries will not abandon it. Environmentalists are more successful when it comes to power and control than liberation.

David Kaczynski read the Unabomber Manifesto in the Post supplement and immediately suspected his brother. Bound by duty, he contacted the FBI, which arrested the terrorist in 1996. After much drama about an insanity defense, or the accused representing himself, Kaczynski took a plea for eight consecutive life sentences without parole.

In prison, he befriended mass murderers Timothy McVeigh and Ramzi Yousef, corresponded with followers, and collaborated on academic editions of two of his books. Cynthia Ozick famously called the Unabomber “an American Raskolnikov,” but if Dostoevsky’s protagonist had the love a good woman, and a meaningful punishment to bring him to redemption, Kaczynski finished his life as a guest of the American taxpayer, secure in his influence over a subculture of dedicated admirers, and in the company of the terrorist troika. I doubt he repented.

There is a unique American strain of scientism, an excessive optimism in scientific progress and its ability to shape a perfect society when fused to the federal government. It’s responsible for the early twentieth century Progressive movement, MK-Ultra, and the current trend of childhood genital mutilations. In the history of technological casualties, Ted Kaczynski was an American original.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

We don’t need to embrace dystopian transhumanist fantasies to optimize our well-being.

John Muir put human inventions aside to reap the benefits of nature.

The Left’s war on nature is integral to its larger project.

Dating apps exacerbate the crisis around forming long-lasting relationships.

You don’t know the machine’s agenda.