The choice of what to let go is no longer yours.

Pursuing God Through His Works

John Muir put human inventions aside to reap the benefits of nature.

April 21 is John Muir’s birthday. Muir is typically remembered as one of America’s foremost naturalists, father of our national parks and a tireless defender of the wilderness. But he might very well have been none of those things. As a young man, Muir was gifted at building machines, and he was set to pursue a career in technology until everything went dark. Literally. Revisiting this little-known chapter of Muir’s life can inspire us to better navigate our own relationship to technology and give us a fresh reason to celebrate his work.

In 1849, Muir left his homeland of Scotland and moved with his family to the backwoods of Wisconsin. Farm work, chores, and family Bible studies kept him busy most waking hours, and he often sacrificed sleep to read and build. The family cellar became his workshop, where he fashioned a host of time-saving inventions, including clocks, barometers, sawmills, and lamplighters. He even conjured up an “early-rising machine,” a bed connected to a clock that tilted the sleeper out of bed and into a pail of cold water at the desired hour each day.

Though his mother hoped he would become a minister, his sisters and friends saw in Muir the makings of a great inventor. Hoping his inventions might lead perhaps to a career as a physician, Muir left home in his early twenties to continue his education and “live a while among machines.” At the Wisconsin State Fair in Madison, his novel contraptions drew praise from spectators and journalists alike, opening doors to employment and further instruction. In college, he continued to indulge his love of creating mechanical devices, including a fire-starting machine and a student desk that automatically dispensed and opened textbooks at desired intervals. At the same time, lessons in botany stoked in Muir a growing passion for nature.

In 1866, Muir took a job at a carriage manufactory in Indianapolis. His work as a machinist prompted his boss to offer him higher wages and the position of foreman. Muir later recalled in his autobiography the difficulty of choosing between two great loves: “I liked the work of inventing and enjoyed the rush and roar and whirl of so many machines—it was a place, that factory, according to my own heart—but the attractions of nature were stronger, and I must sometime get away.”

The following year, while repairing a machine belt at work, the sharp end of a file pierced Muir’s right eye, temporarily blinding him in both eyes. He was confined to bed and a dark room for several weeks. Fearful he might never regain his sight, Muir was comforted during his recovery by visitors reading to him and by correspondence from loved ones. One such letter from his lifelong friend and mentor Jeanne Carr encouraged Muir to be patient and hopeful: “I have often in my heart wondered what God was training you for. He gave you the eye within the eye, to see in all natural objects the realized ideas of His mind…He will surely place you where your work is.”

The Muir who emerged from the dark room was more anxious to travel than ever, determined to store his mind with as much natural beauty as he could before another accident could stop him. As he put it years later in The Story of My Boyhood and Youth: “I made haste with all my heart, bade adieu to all thoughts of inventing machinery and determined to devote the rest of my life to studying the inventions of God.”

With thoughts of California’s Yosemite Valley already swirling in his mind from brochures he had read, Muir decided to first satisfy a long-held desire to traverse the wilds of the American South. In the fall of 1867, he embarked on a thousand-mile walk to the Gulf. Facing unfamiliar territory with a renewed sense of purpose and urgency, Muir wrote in a letter a few days before his journey that he would be “carried of the Spirit into the wilderness.” With this excursion, the Muir many of us recognize today begins to take shape.

Though Muir committed himself to spending the rest of his life studying nature, he did not discard his mechanical inclinations overnight. In the winter of 1869, he built a sawmill for James Hutchings, the Yosemite Valley’s first permanent resident. A few years later, he asked one of his brothers to send a trunk full of his tools and models to him. While he lived in the Sierra Nevada mountains, he continued to use his own clocks to keep time and his singular alarm clock bed to get him up each morning. Even in the wilderness, Muir did not abandon human invention. He continued to use it as a tool.

Today, we live in a technological age that is by turns exhilarating and bewildering. As we navigate the challenges of AI, social media, and smartphone use, we need the benefits nature can give us now more than ever. Muir was passionate about machines, but he was willing to put them aside for the healing, perspective, and inspiration he found in the wilderness. Can we look up from our screens long enough to do the same? Here are two ways you can follow Muir’s lead and pursue the inventions of God yourself.

First, get a bigger dose of wild. Muir could hardly contain himself in his praise of nature’s bounty: “Every landscape…and every one of its living creatures…and every crystal of its rocks…is throbbing and pulsing with the heartbeats of God.” All right for him, you might think, but what about us? According to a recent survey, most of us spend free time in nature at least once a month. But that may not be enough. A 2019 study reported that at least two hours a week in natural environments was associated with better health and wellbeing. That means a whole host of advantages, from reducing inflammation and mental distress to boosting cognitive function, improving sleep, and even protecting our vision.

A walk in the woods might provide an optimal dose of nature, but any natural setting that includes greenery, fresh air, and sunlight will serve. Build into your weekly calendar a few forays into natural spaces. And every now and then, take your shoes and socks off and walk barefoot in the grass. This conductive contact between our body and the surface of the earth is known as grounding or earthing. It has a positive effect on our physiology and health, reducing inflammation and helping with pain relief and wound healing. You don’t have to sell all your stuff and go live off-grid to tap into the benefits of nature, but you will have to be purposeful. The good news is that you’ll start to feel results as soon as you make the effort.

A second way to follow Muir’s example is by nurturing your inner life. We are endowed with the formidable power of our intellect, but these days, we’re living more reflexively than reflectively. We’re avoiding the activity of just thinking, because we consider it a waste of time. A recent study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology compared expectations of thinking with the actual experience of doing it. Across the board, participants reported greater interest and engagement than they had anticipated beforehand.

Each type of thinking provides its own mental benefits. For example, daydreaming is our uniquely human ability to alternate between fantasy and reality. It’s a force that can inspire change and make life more bearable at any age. Mind wandering, or “stream of consciousness thought,” allows us to generate novel, creative thoughts and gives us a space to consider obstacles to our goals. Even nostalgic thinking, often considered detrimental in the past, can provide us with a reservoir of meaning and give us a sense of continuity between our present and our past. Boost your clarity and motivation by working up to at least 20 minutes a day of thinking without distraction.

If Muir were still with us, he’d no doubt be intensely intrigued by our modern technological society. We’ve come a long way. And yet, for all our advancement, we still need what was here all along. And we need people like John Muir to remind us.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

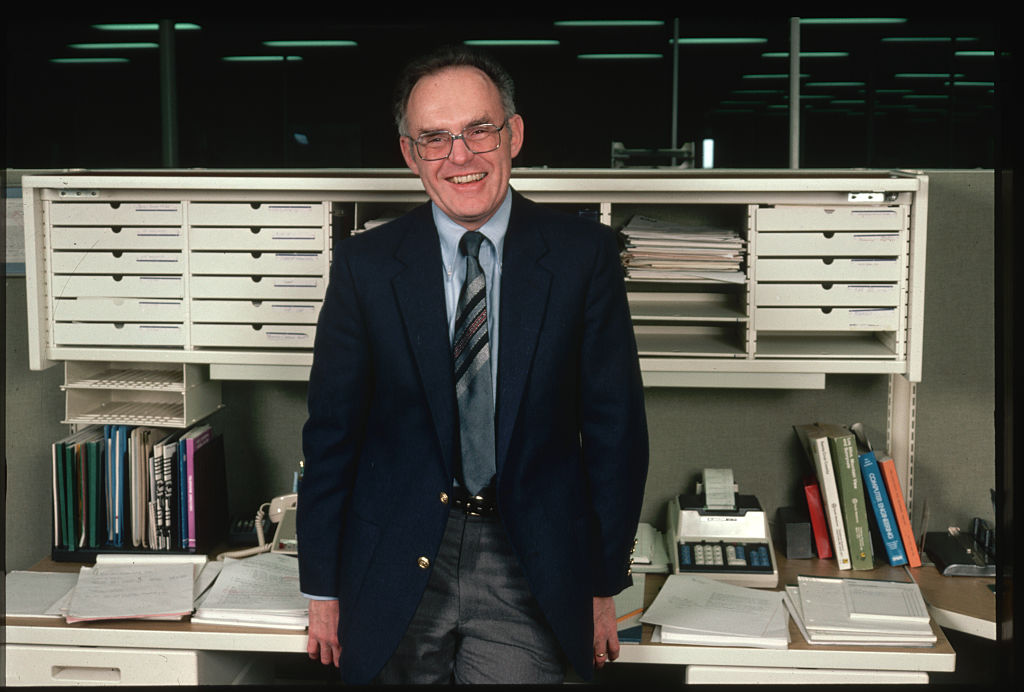

Gordon Moore was the last of the great twentieth century American innovators.

We don’t need to embrace dystopian transhumanist fantasies to optimize our well-being.

The Left’s war on nature is integral to its larger project.

Dating apps exacerbate the crisis around forming long-lasting relationships.

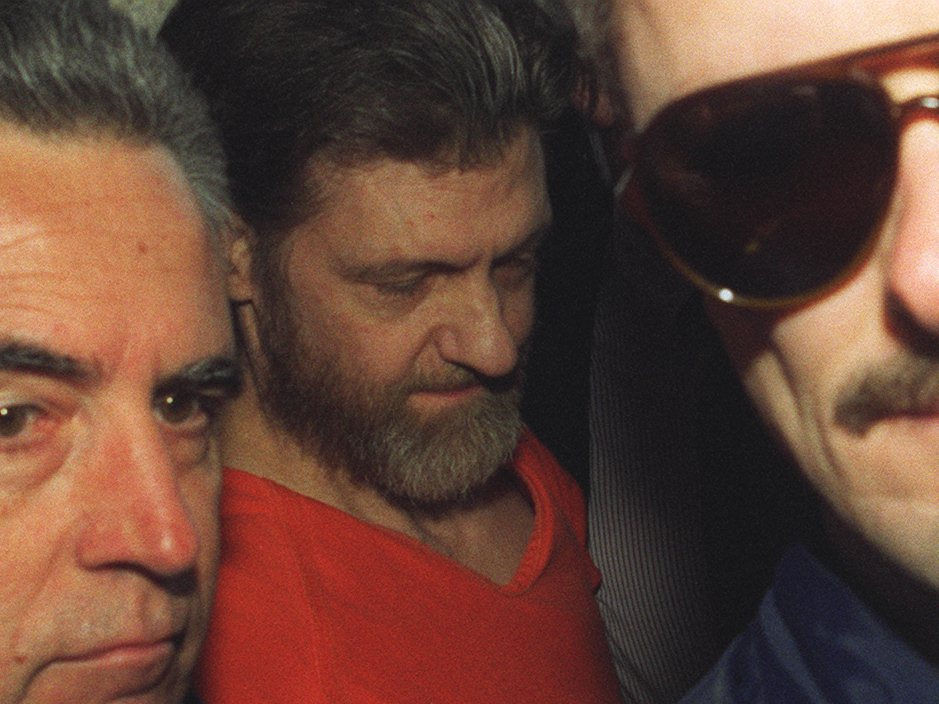

The Unabomber worshipped and rebelled against the false god of technology.