Morning Edition’s Steve Inskeep tried to reconcile America’s love of equality with its history, but it’s getting harder for many Americans to square that circle.

The Art of Being Dependent

Progressives want a nation of subjects who are at the mercy of the state.

When Alexis de Tocqueville published Democracy in America, he warned against the typically democratic doctrine of “individualism,” meaning the belief that one has no need of his fellow citizens and hence has only minimal obligations to them. As the characteristically American remedies for that doctrine, he highlighted two elements: the principle of “self-interest rightly understood,” or long-term interest (seeing how one’s self-interest in the long run will best be served by promoting the community’s good), and the “art of association,” through which Americans combined, on a voluntary basis, in groups that worked to advance causes that benefit the community (churches, the United Way, the Boy Scouts, and Big Brothers Big Sisters of America to name only a few contemporary examples). Precisely because these movements were voluntary, they did not endanger the spirit of self-help that Tocqueville admired in America, through which people did their best to advance themselves and their families by means of their own work and enterprise.

By contrast, the doctrine of individualism would leave us helpless wards of a “tutelary” despotism. Such a government, even if it were elected, would remove from individuals the very capacity to administer their private affairs, instead relying on a bureaucracy that knew what was best for them.

Today’s progressive liberals have turned Tocqueville on his head. During the 2012 presidential campaign Barack Obama, inspired by the previous senatorial campaign of Elizabeth Warren, memorably proclaimed to those who had prospered in America, “You didn’t build that!” In particular, he told business owners, “If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that”—because “somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges.” This argument was intended to reduce the pride that successful American citizens take in their accomplishments by making them realize how much those accomplishments were really the doing of previous generations of citizens acting under the direction of government.

This argument implied a disparagement of the notion of private property in favor of the belief that property is something we enjoy thanks to the government, a notion advanced by such liberal academics as Stephen Taylor Holmes and Cass Sunstein in The Cost of Rights: Why Liberty Depends on Taxes. (Their claim echoed that of the Progressive economist Edwin Seligman, an early advocate of establishing a federal income tax, who argued that rather than being payments for government services, taxes should be regarded as obligatory “because the state is a part of us.”)

Whereas Tocqueville praised Americans’ associative art precisely because it enabled them to do things for their communities that did not depend on coercion by a centralized government, today’s progressive liberals increasingly would do the reverse. During his 2008 presidential campaign, Obama quoted a letter he reportedly received from a middle school girl in South Carolina, describing a leak in the roof of her school and asking whether the government could fix it. In Tocqueville’s time, a group of local men might have gotten together to repair the roof. Even now, most Americans would think of this as a task for local government. But Obama apparently saw no ground for the distinction between federal and local responsibilities: responding to a “Rebuild America’s Schools” coalition, composed of teachers’ unions and other education lobbies, he announced a Federal School Modernization program that would supposedly address student learning problems by financing school repairs, without the need for state or local contributions. (While billions were spent, no overall improvement in student performance was ever reported to result.)

The reversal of the traditional American spirit lauded by Tocqueville has been carried to a further extreme in a March 12 New York Times column by Alissa Quart, the author of a forthcoming book entitled Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves from the American Dream. In the column, headlined “We All Depend on Someone. Let’s Celebrate That,” Quart acknowledges that “from a child’s earliest age, independence is extolled as a virtue” and remarks that “some independence,” such as a child’s “picking out her books” and later learning to take the train to school, is “worth honoring.” But she adds that “other strains” are “not as positive.” Her initial examples embody failures of the government to meet the individual’s needs or wants: suffering illness “without adequate health coverage,” “having to take care of our children entirely on our own…without a state-supported nursery in sight,” and having to take out loans to finance our own or our children’s education.

Quart invents a straw man of people so committed to “pull yourself by your bootstraps” individualism that they see “even asking for help” from other individuals—even “close ‘friends and partners’”—as “something to avoid at all costs.” To overcome such attitudes, Quart urges that we learn to “value…the power and skill of being dependent.” For instance, obtaining government social service benefits often requires the “administrative burden” of employing “effort, knowledge, and sheer time” to fill out applications. It similarly takes “craft and skill” to “feed a family of five on minuscule monthly food benefits” or “get childcare and find bosses who tolerate or even encourage taking sick leave.” After all, Quart reminds us, even the “privileged…rely on tax breaks, colleagues and social connections, roads, telecom, infrastructure, health insurance, and their employees.” So why shouldn’t other people similarly rely on government-provided personal benefits?

When Lyndon Johnson launched the War on Poverty in 1964, he proclaimed its goal as not to turn the poor into permanent dependents but “to allow them to develop and use their capacities” to share in America’s “promise.” The success of the War on Poverty fell short of Johnson’s promise for reasons documented in such works as Daniel Moynihan’s Maximum Feasible Misunderstanding and Charles Murray’s Losing Ground. But had Johnson described its aim as being to help foster the “art” of dependency, it is unlikely that even a heavily Democratic Congress would have enacted it. Self-described liberals and progressives of the sixties still shared in the fundamental American belief that while government must assist needy individuals not sufficiently able to take care of themselves, the goal of such assistance is to enable its beneficiaries to stand on “their own two feet”—not excluding, of course, the help of their friends and family members.

Today’s progressive liberalism has traveled a long way in the nearly six decades since LBJ spoke. The rapid expansion of government assistance, including a broadening of eligibility standards, has generated a substantial class of what economist Nicholas Eberstadt calls “men without work.” Their days are taken up largely, as he reports, with drug use, social media, and other nonproductive enterprises that benefit neither themselves nor their community. Meanwhile, as economists Phil Gramm and two colleagues report in The Myth of American Inequality, the overall provision of income supplements or substitutes and various government subsidies (food, housing, etc.) to the lowest income recipients who pay no income taxes has elevated unearned incomes to the point where blue-collar and lower-middle class workers often make little more than what they might receive by not working.

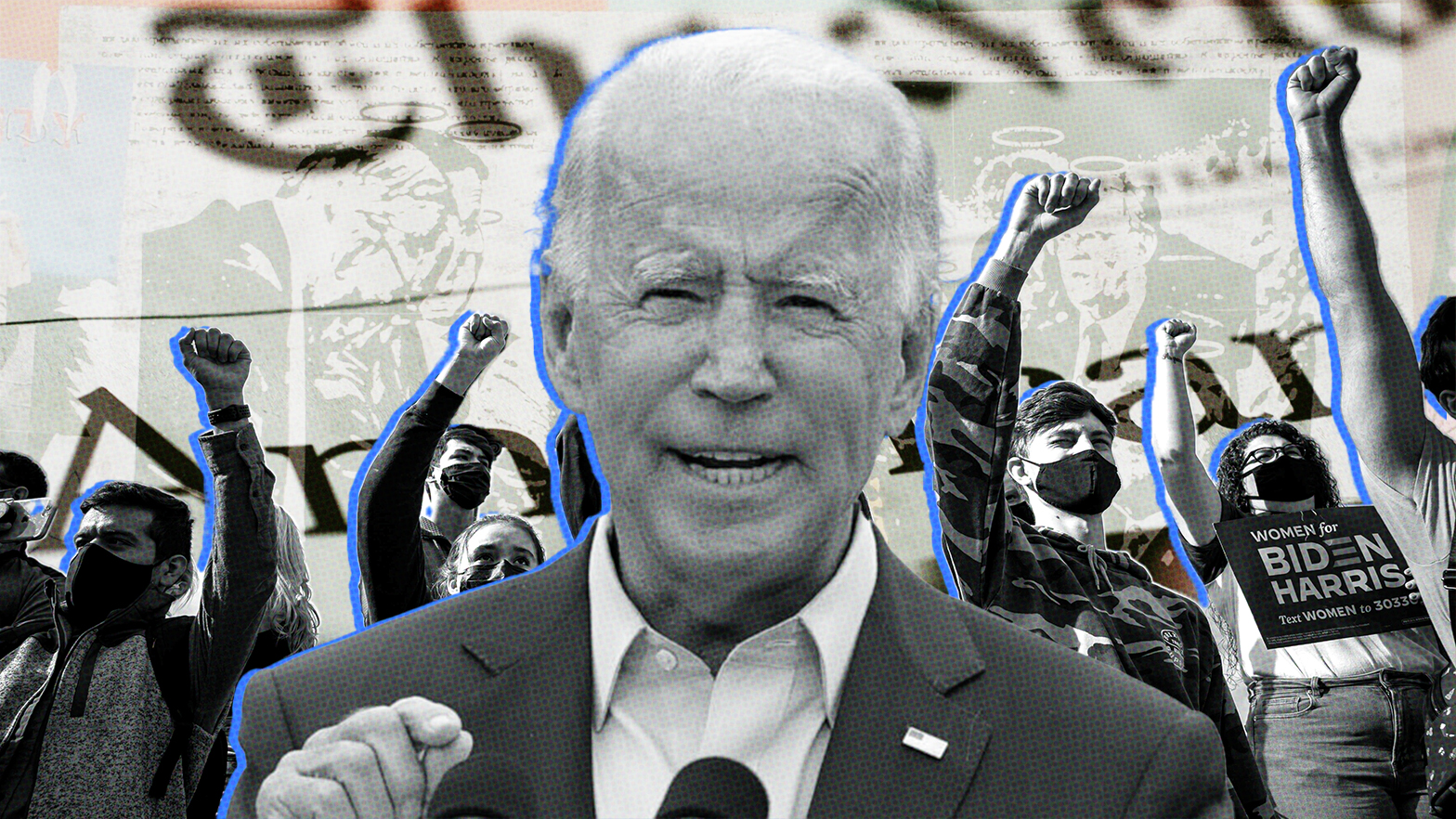

No country built on a moral foundation like the one Quart proposes can long survive as a free regime—if, indeed, it can survive at all. America can afford to provide the generous social benefits it already distributes to the ill, the elderly, and the poor only thanks to the industry, inventiveness, and associational skills of those who aspire to self-sufficiency, which they do not regard as a myth. The truly dangerous delusion is the one espoused by Progressives and socialists like Quart, Bernie Sanders, AOC, and Presidents Obama and Biden: an ever-growing bounty of benefits to be distributed among favored classes at the expense of a declining class of workers and independent-minded citizens.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Wokeism stamps out the very idea of individual character formation.

Young Nietzscheans should look to Tocqueville as a more politically responsible source for a new politics.

A little less conversation, a little more action.

And how to unlock ourselves.

A troubling trend of social isolation is afflicting young adults globally.