Conservatives need to be a lot savvier about how they vet judicial candidates.

Behind the Declaration

Morning Edition’s Steve Inskeep tried to reconcile America’s love of equality with its history, but it’s getting harder for many Americans to square that circle.

This Fourth of July, Morning Edition broke with its 33-year tradition of marking the holiday with a reading of the Declaration of Independence in favor of a segment on “what equality means and has meant in this document.” You would never have guessed it from the angry Twitter comments, but the segment was a normal, level-headed account of how different groups—namely, women and African-Americans— have embraced the Declaration’s assertion that all men are created equal in their fight for equality.

What is troubling about NPR’s decision not to read the Declaration was not the segment itself, which ended with host Steve Inskeep exhorting “later generations to keep alive” the transcendental “purpose” that the Declaration gives our republic. What was troubling is the cultural context that led NPR to deem such a segment necessary. That is, the fact many Americans now believe that equality is opposed to their country’s purpose—that the Declaration is a self-serving lie penned by a hypocritical slaveholder.

Previous understandings of equality in the United States understood it as central to our country’s purpose. The Declaration of Sentiments drafted at our nation’s first women’s rights convention echoed Jefferson’s language by proclaiming the “self-evident” truth “that all men and women are created equal.” Frederick Douglass identified the fight to end slavery with the nation’s Founders, calling the Constitution “a glorious liberty document” that contains principles “entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.” Many leaders of the civil rights movement followed the same strategy. Martin Luther King, Jr. called the Declaration’s proclamation of equality a “promissory note” made out to Americans of all races, and called for the U.S. to make good on this promise.

Nevertheless, it is understandable why some Americans would question the historicity of our nation’s commitment to equality. After all, many of our Founders held slaves. How could these men possibly be advocates of equality?

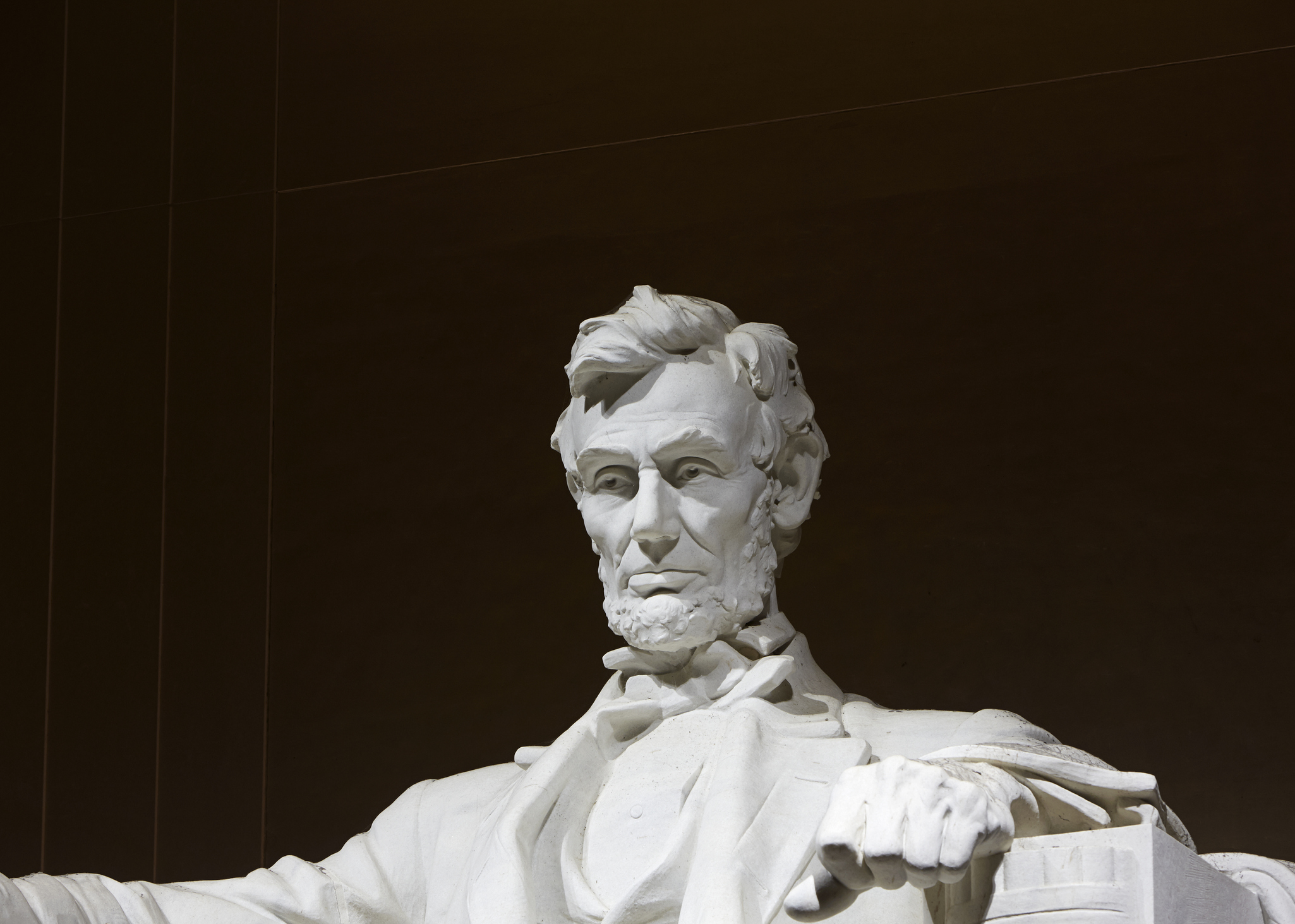

One answer is found in Abraham Lincoln’s 1854 Peoria speech, which he gave in opposition to the expansion of slavery into territory that had been declared free under the Missouri Compromise. In a meticulous, lawyerly study of the Founder’s attitudes, Lincoln shows how they accepted slavery where they were compelled to, but had, in some of our nation’s earliest legislation, “hedged and hemmed it in to the narrowest limits of necessity.” “The plain unmistakable spirit of the age,” says Lincoln, “was hostility to the principle [of slavery], and toleration, only by necessity.”

But you don’t have to take Lincoln’s word for it. The Confederate states also saw the United States as a nation committed to equality — and from their perspective, that was the problem. In his “Cornerstone Speech,” Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens said that “the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution [believed] that the enslavement of the African was…wrong in principle, socially morally, and politically.” According to Stephens, the Founders’ belief in equality was “fundamentally wrong,” and the Confederacy was to improve upon the United States by founding itself on a belief in natural inequality.

The North fought for equal rights, identifying their purpose with an embrace of America’s history and principles. By contest, the South fought for a racial caste system, identifying their purpose with a rejection of that same history and those same principles.

This is why so many advocates for equality have embraced the Founders and their principle that all are equal in their possession of certain inalienable rights. Today, however, those principles are being challenged by the material inequalities that persist despite everyone’s shared moral equality. These criticisms are raised by advocacy groups like Black Lives Matter and the academic tendencies of Critical Race Theory. To this end, we have grown unfamiliar with what equality actually is.

Contrary to how some advocates would have it, equality is not when and only when all social groups of any kind have the same amount of stuff. Such thinking wrongly holds every inequality to be an instance of discrimination. On the contrary, it is precisely our equality of opportunity that will lead to inequality of result as different people make different choices. Countries with the strongest traditions of gender equality, for example, tend to see a stall or even an increase in income inequality as men and women choose different jobs to suit their different work preferences—a phenomenon some call the “Nordic Paradox”.

Furthermore, legislating in order to reduce disparities among groups often requires us to resume the practice of making racially or sexually discriminatory laws. If disparities between these groups are not the result of discrimination but of the different decisions that members of these groups make, then such policies are questionable at best. As Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson points out, the desire for blacks to adopt the financial habits of whites can be a veiled form of racism. If the black middle class “has lifestyle preferences that direct it away from the asset accumulation tradition of Euro-American suburbanites,” Patterson writes, “then such choices are entirely their business, and it is an impertinence for bourgeois liberals to bemoan them.”

On the other hand, rampant inequality is harmful to democratic government. To neglect the real problem of inequality in the United States by hiding behind the free market is undemocratic and cowardly. Simply put, America’s political and moral life cannot function unless most people have roughly the same amount of stuff most of the time, and they must feel they have a say in our nation’s politics. People with vast amounts of wealth will tend toward corruption, and people who feel disenfranchised will be suspicious of their government.

It is just and reasonable to expect that low-income Americans should share in the fruits of America’s material progress. At the same time, we need to tolerate some inequalities if we are to maintain our rights and freedoms. A just society will address new concerns about racial and economic inequalities with creative policymaking, while also respecting our freedoms and being honest about the causes of those inequalities.

Tocqueville warned that “democratic peoples have a natural taste for freedom” but love equality much, much more. Democratic peoples, “want equality in freedom, and if they cannot get it, they still want it in slavery.” Equality is good, but it is not an unalloyed good, and if we are blinded by an ardent and unreflective love of equality, we will lose much in the process.

Morning Edition was right to connect the cause of equality with the men behind the Declaration of Independence. But equality is a slippery thing, and will be a perennial subject of conversation, as it has been throughout our history.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Young Nietzscheans should look to Tocqueville as a more politically responsible source for a new politics.

Progressives want a nation of subjects who are at the mercy of the state.

Wokeism stamps out the very idea of individual character formation.

Happy Thanksgiving to you and yours.

Wokeness is threatening our nation's historic sites.