Marlene Dietrich was good for morale.

Reductio ad Hitlerum

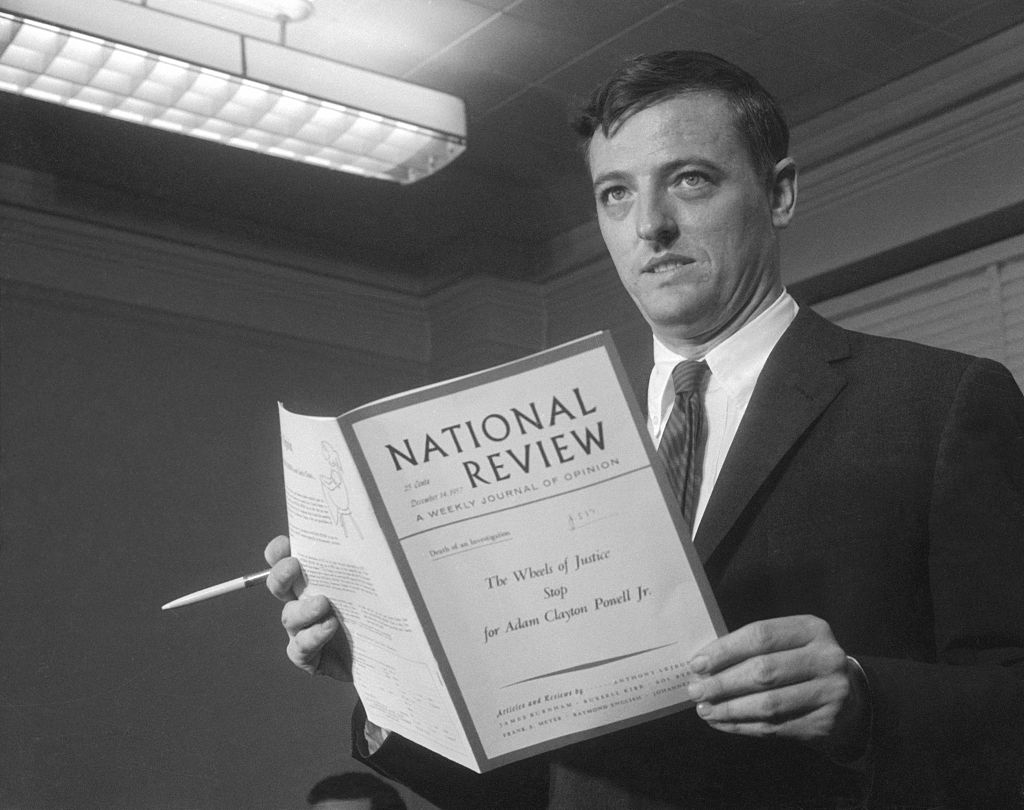

National Review's failure to grasp the friend-enemy distinction is revealing.

This is about National Review, who isn’t worth giving a lot of consideration—by you or me—so I’ll try to keep it short.

One of the pitfalls of success in social media-saturated modern America is you get a lot of concern trolls. The “Claremont school” of conservatism—broadly understood as people educated at the Claremont Graduate School by Harry Jaffa and his students, plus those who became fellow travelers—has risen in prominence over the last decade or so.

This has occasioned much tut-tutting that we have somehow betrayed our principles, or our teacher, in particular for saying nice things about Trump. That article (or tweet thread) has been written so many times that you’d think people would get tired of it and stop offering fresh examples.

But here comes NR with another entrant. Mike Watson, of whom I have never heard, is the author. Did he go to Claremont? Attend any of the Claremont Institute’s fellowship programs? Spend any time with Jaffa at all? Not that I know of. Why, then, does he feel especially qualified to tell those of us who did what our “true” principles are and what they (allegedly) require us to conclude?

One of the maxims of Jaffa’s great teacher Leo Strauss was that, before one can accurately or usefully criticize a thinker (or body of thought), one must first understand him exactly as he understands himself. Like all of our concern trolls, Mike Watson believes that he understands Claremont as well as, or better than, the Claremonsters.

But he doesn’t. In fact, he doesn’t seem to understand us at all.

I’m not going to refute Watson’s claims point-by-point (although I easily could, but who cares). However, one is deserving of examination, since it has been made dozens of times before, will no doubt be made dozens of times more, and demonstrates Watson’s lack of familiarity with the issues and materials at hand.

Watson may think he is being original in comparing us to Carl Schmitt, the German jurist and political theorist who joined the Nazi Party in 1933, served the Nazi state until coming under Party suspicion three years later, and yet in 1985 went to his grave apparently unrepentant. But this facile comparison has been done to death over the last six years. Maybe Watson doesn’t know that; but didn’t any of his editors?

Like his concern troll forebears, Watson finds a commonality between Schmitt’s most famous idea and some of the more recent arguments coming out of the Claremont school. Watson doesn’t come right out and call us Nazis; he’s too polite or pusillanimous for that. He just writes an entire piece comparing everyone with influence on the contemporary right, including us, to the second-most famous (after Martin Heidegger) thinker who joined the Nazi Party. The reader is left to draw his own conclusion. And what else is he supposed to conclude?

As to the “substance” (such as it is) of Watson’s claim, the aforementioned “most famous idea” of Carl Schmitt is his assertion that the friend-enemy distinction is the foundation of all politics. Watson finds this, and thus by extension us, whom he accuses of subscribing to it, anathema.

That’s about the only thing he gets right. We do believe the friend-enemy distinction is fundamental to politics. Why? Because it is. Where do we get this idea? From our teacher, Harry Jaffa, whom Watson accuses us of betraying. Where did he get it? From his teacher, Leo Strauss, who got it from Plato and Aristotle, and, one may say, from observations of and reflections on the nature of things.

A word needs to be said about Strauss and Schmitt. Like all the other concern trolls who invoke Schmitt to trash us, Watson seems to think that simply to cite “Schmitt-the-Nazi” is to win the argument ad uno tratto. But if that were the case, then he would also be delivering a knock-out punch to Strauss and to his student Jaffa, from whose teachings we are said to have woefully departed.

Watson is apparently unaware of the great respect in which Strauss and Schmitt held one another, or of Strauss’s qualified esteem for Schmitt’s work (as opposed to his political activities), which Strauss passed on to his own students, including Jaffa, who passed it on to us. Strauss and Schmitt knew one another personally and did each other important services. Schmitt was instrumental in getting Strauss the grant money that allowed him to leave Germany in 1932. Strauss privately wrote to Schmitt the most penetrating and detailed criticism of his major work, The Concept of the Political, that Schmitt received from any quarter. Schmitt later enthused that Strauss “saw through me and X-rayed me as nobody else has.”

Schmitt’s works (and Strauss’s notes on them) are long, complex and defy easy summary. Those interested will want to turn to the originals. There is also a fine overview, Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss: The Hidden Dialogue, by Heinrich Meier.

For present purposes, we may say the following. Schmitt’s admission that Strauss “saw through” him is perceptive. Strauss does not denounce Schmitt’s core insight; rather, he thinks it through to its roots and assesses not just its strengths but its ultimate inadequacy. This is, one hardly need add, far from the glib dismissal we get from the likes of Watson.

Strauss many times pointed out that, of the three definitions of justice proffered in Book I of Plato’s Republic, only one survives the transition to the perfectly just city or “city in speech.” And that is the view that justice is helping friends and harming enemies. If we want to be absolutely strict, we would immediately clarify that Socrates denies that justice entails harming anyone, but he does so by defining “harm” in such way that offends ordinary common sense (e.g., deserved punishment is not harm; cf. the Gorgias).

Socrates does not, however, deny the friend-enemy distinction. To the contrary: he builds his whole political philosophy thereon. His just city emphatically begins, and never retreats, from recognizing that all politics is particular. There will always be borders, citizens and non-citizens, and hence friends and enemies. This does not mean that every non-citizen is always an active enemy combatant, but he is always potentially so and never a friend in the same way the fellow citizen can and must be. The eternal and inevitable presence of potential enemies is why there must be a “guardian” (later renamed “auxiliary”) warrior class.

For Strauss, this basic insight, fundamental to all politics, is a necessary starting point from which one must ascend to discover, and eventually implement, true justice, or the closest approximation practicable in the real world. Hence for Strauss, Schmitt’s theory is not so much wrong but incomplete. To tell a very long story in very few words, for Strauss, Schmitt’s thought is but another attempt to address fundamental problems of late modernity that end up either relying on or even radicalizing faulty modern premises. Strauss credits Schmitt (as he credits Heidegger) with seeing late modernity’s dead-end more or less clearly but criticizes him for not fully thinking through the implications of his own ideas. For Strauss, the only way forward is a return to ancient modes of thought that nearly all of his contemporaries, including Schmitt, considered decisively refuted and, thus, of only historical interest. Strauss alone showed that they were wrong.

I wouldn’t expect someone like Watson, or anyone at National Review, to know any of this. It’s abstruse, academic stuff. But if they don’t, they shouldn’t write about or publish on it. It’s embarrassing for them (or should be) and disrespectful to the memories of great men (Strauss and Jaffa). It’s also meretricious and low to refer to people whose ideas they don’t understand as Nazis.

One reason the genuine right considers National Review a joke is that the magazine long ago lost the ability to distinguish between friends and enemies. NR spills considerable ink cozying up to the left and trying to show that they are not like those unacceptable bad conservatives but are instead harmless and reliable good guys. It attacks and backstabs those who ostensibly are, or should be, its friends and sucks up to its supposed enemies. Or perhaps NR is simply lying to its readers—and donors—and is playing Schmittian politics after all, but having switched sides? I couldn’t say, but that explanation fits the observable facts.

National Review presents itself as the flagship publication of American conservatism, but then goes around calling conservatives it doesn’t like Nazis. Those who call you Nazis are not your friends but your enemies. No one who is not a fool takes advice from his enemies, or assumes that said advice is well intentioned. It may be useful, even necessary, to know what your enemies are saying about you, but that’s about as far as it goes. In the case of NR, which as best as I can tell no longer has much influence, it doesn’t even go that far.

Not long ago, when National Review transitioned to a new editor—only its fourth in the magazine’s 67-year history—I mentioned this to a prominent conservative intellectual. That is, prominent in the relevant new right, not the irrelevant establishment grifter “right.”

“When did this happen?” he asked me, clearly surprised.

“I don’t know,” I replied. “Three months ago? Maybe six?”

“What does it say,” he mused aloud, “that National Review, whose smallest masthead changes used to be big news on the right, got a new editor and I didn’t even know it?”

It says it all.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Our teacher and friend trained us to find the safeguards of self-government through political philosophy and poetry alike.

The Left trivializes real totalitarianism.

Leo Strauss and Russian Heideggerianism.

Alec Ryrie’s unsatisfying answer to escaping the Age of Hitler.

The Leo Strauss Dissertation Award.