The movement has been given an heir.

Look Who’s Counting

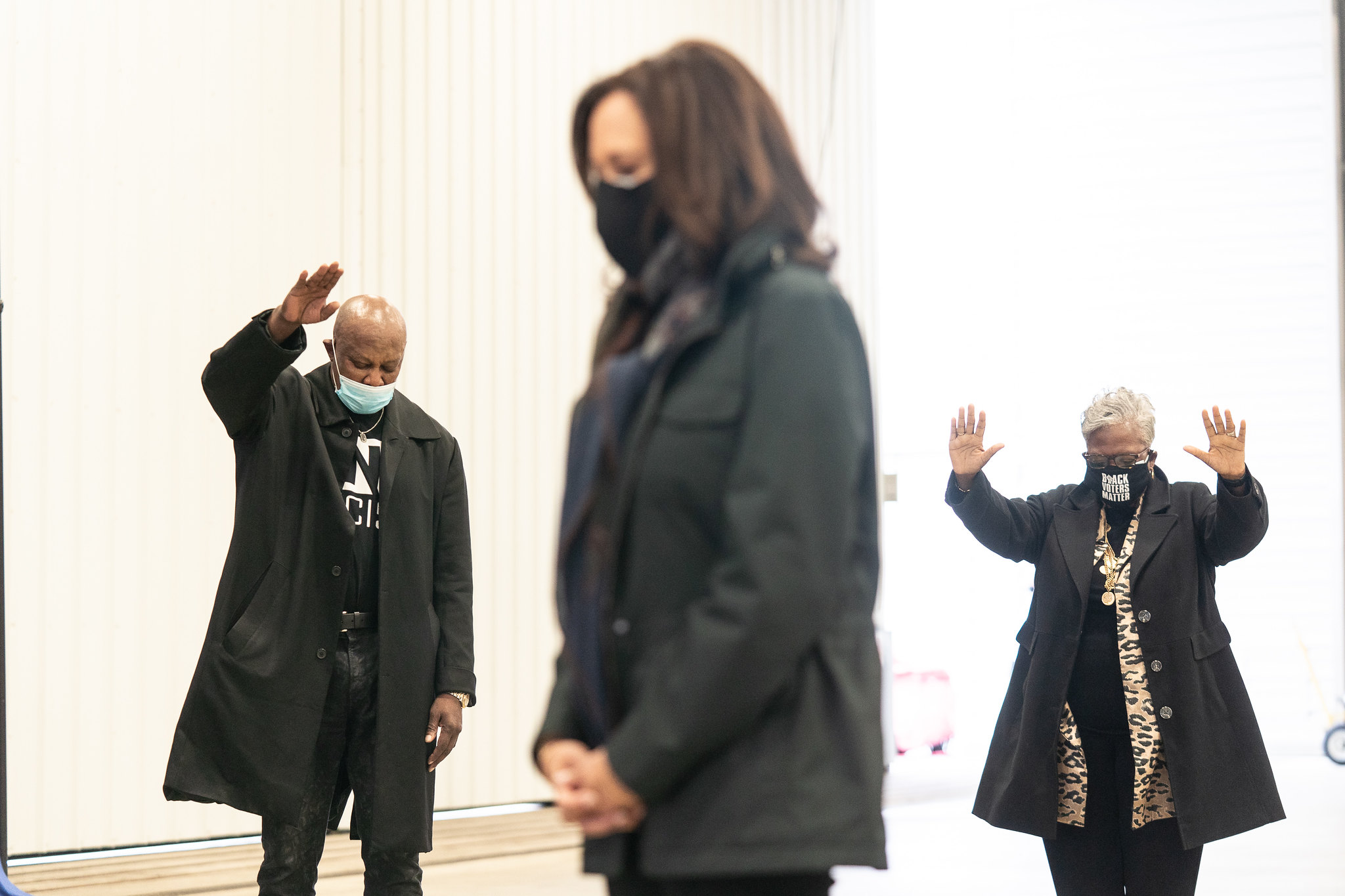

In 2024, might Kamala Harris do what Mike Pence did not?

On January 6, 2025, Kamala Harris, presiding over a joint session of Congress in her role as President of the Senate, will open the electors’ votes for President. Suppose she believes that changes in the voting laws of Georgia and Arizona, which prohibit vote harvesting and universal mail-in ballots, have depressed minority turnout. Could Harris refuse to count these suspect votes, deprive a Republican of enough electors to win, and award the Presidency to incumbent Joe Biden, or even herself?

President Donald Trump’s challenge to the 2020 elections revealed ambiguities in our electoral system that might encourage Harris to execute this very maneuver. Advised by Claremont Institute fellow John Eastman, Trump argued that Democratic voter manipulation had deprived his electors of their victories in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Arizona, and Nevada. Trump argued that Vice President Pence could either reject these votes or delay their counting to allow for reconsideration by the state legislatures.

Eastman’s theory took advantage of the Constitution’s silence on disputes over electors. The Twelfth Amendment states only that “[t]he President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.” Use of the passive voice leaves unclear the mechanism for judging the legitimacy of the electors. Vice President Pence, however, concluded that the Constitution left him with no discretion to overturn the results of the popular votes in the disputed states. Some Republican Members of Congress attempted to use the terms of the 1887 Electoral Count Act to reject the electors, but the attack on the Capitol interrupted their efforts. After law enforcement restored order, Congress rejected the challenges and recognized Biden’s victory. Eastman’s theory has come under withering attack from the House special committee on the events of January 6, supporters of Vice President Pence, such as ex-judge Michael Luttig, and, in the Claremont Review of Books, Claremont McKenna College Professor Joseph Bessette.

We believe that a careful consideration of the constitutional structure provides far more support for Eastman’s analysis of vice-presidential discretion than these critics appreciate. Drawing on the work of other constitutional law scholars, we proposed a similar theory in The American Mind the month before the election. But does vice presidential judging of the votes, plus the independent authority of the state legislatures to choose the electors, mean that Harris and future Vice Presidents will be able to throw close elections into the House or even to themselves?

We believe not. The fundamental flaw in Trump’s challenge came not on the law, but in the facts. The 2020 elections simply did not give rise to any legitimate disputes over which Vice President Pence could exercise dispute resolution power. No branches of any state government sent dueling slates of electors. No state or federal court found any fraud or error in the state selection of the electors. No legitimate institution of any state or federal government cast doubt on the popular vote. No slate of electors nominated by a party or other private group can simply certify or self-appoint itself as the state’s electors and thereby trigger a “disputed” election—otherwise, a losing candidate could contest the legitimacy of every future election.

The electoral college system remains fundamentally anchored in federalism, as our departed friend Michael Uhlmann often reminded us. The constitutional text grants the states alone the power to “appoint” presidential electors. Article II declares that “[e]ach State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,” a “number of Electors” equal to the state’s combined representation in the federal senate and house.

After the electors have cast their votes, and sent their votes to the Vice President as President of the Senate, Congress has only an incidental role in the counting of the electors’ votes. Under Article II, “Congress may determine the Time of chusing the electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which shall be the same throughout the United States.” As the Supreme Court observed in In re Green (1890), other than prescribing these two dates, Congress’s only other role is to witness the opening of the votes.

Congress has indeed specified the date on which the electors’ votes are to be counted in the presence of both houses; but that is more a matter of housekeeping than it is a substantive intervention in the electors’ appointment or voting. While the Twelfth Amendment uses the passive voice for the power to count the electors, the amendment does not expressly authorize or mandate that Congress shall do the counting. Rather, the houses of Congress seem to be “presen[t]” as witnesses or spectators in a public ceremony. The amendment gives Congress a substantive role only if the counting does not yield “a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed.” In that circumstance—but only then—are any congressional powers activated: the selection of President goes to the House, which votes by state delegations.

These finely wrought procedures received detailed attention during the Framing, and again in the drafting and ratification of the Twelfth Amendment in 1800. The Founders conspicuously leave Congress out of the counting of the electoral votes except as an observer. Contrast the Twelfth Amendment’s silence with the Constitution’s broad grant of discretion to Congress over other elections. Article I grants Congress the power to override state regulations on the “Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives,” with only an exception for the “place for choosing Senators.” Article I also assigns each house the power to “be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members.” If the Framers had wanted Congress to pass judgment on the appointment or qualifications of presidential electors, they knew how to say so.

The Constitution’s structure and history support this reading of the text. In the Framers’ view, the separation of powers ensures that the government operated within its written limits–a prerequisite to the protection of individual liberties. The Constitution equips each branch of the government to maintain its independence and fight domination by the others. To that end, the Constitution insulates the election of the President from congressional interference (except when the electoral college fails to produce a winner). If Congress could effectively determine the outcome of that electoral process, it could undermine the independence of the national executive.

Failures in state government during the critical period after Independence had taught the Founding generation the value of an independent executive. Madison described the state governors as “little more than Cyphers.” Legislatures rather than voters usually chose the governors (New York and Massachusetts were exceptions), and the governors could take no significant decisions on their own (they typically had short terms, no veto, and no appointive powers). Some state constitutions and laws expressly provided for the legislature to resolve disputes over executive elections. These states included Delaware, Pennsylvania, and (by statute) New York. The Framers did not adopt any of these models.

Early history under the Constitution similarly supports a state-centric view of the presidential selection process. Not long before the presidential election of 1800, Congress debated where authority lay for resolving disputes over the electoral vote. Senator Charles Pinckney, himself an influential framer, opposed the effort to establish a committee that would decide which electoral votes had been duly certified by the state legislature. Where did these powers lie then? For Pinckney, the answer was “exclusively” with the state legislatures.

Congressional Claims

Congress began to claim the power to review the validity of electoral votes, with increasing insistence, during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Those claims culminated in the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (the ECA). Proposals to replace the ECA have relied on the assumption that Congress has the power to resolve disputes over electoral vote counts. In his CRB debate with Eastman, Bessette similarly concludes that Congress, not the President of the Senate, must have this authority as well. But the longevity of the ECA does not confirm its constitutionality. As the Supreme Court wrote in 2020, a development that “arose in the second half of the 19th century … cannot by itself establish an early American tradition.”

Article I, Section 8’s “Necessary and Proper” clause provides the leading text in favor of the ECA and similar legislative proposals. The meaning of the “sweeping clause” (as it is known) has been debated since the Washington Administration, and formed the fulcrum of Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion in McCulloch v. Maryland. To allow the sweeping clause to give Congress the authority to resolve electoral disputes would be akin to saying that the Framers had carefully locked all the doors of a house, but then left behind a master key that would open them all. Whatever the scope of the sweeping clause, it cannot be construed to empower Congress to “legislate in all cases for the general interests of the union”—language that the Philadelphia Convention considered and ultimately rejected.

Nor does the Necessary and Proper Clause authorize Congress to seize powers belonging to others. Instead, it allows Congress to implement the original allocation of authority. The clause gives Congress the power to enact legislation that is “necessary and proper” to carry “the Foregoing Powers”—the powers enumerated in Article I, section 8—into execution. The power to resolve electoral disputes is not enumerated in section 8.

Next, Congress has the power to enact “necessary and proper” legislation for executing “all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States.” These powers are those “vested” in one of the three branches of government by Articles I, II, and III. The reference to “all other Powers vested by this Constitution” seems naturally to include the powers vested in Congress outside Article I, Section 8. For example, under Article IV, Congress may admit new states to the union or dispose of or provide rules and regulations regarding federal territory or other property. The Reconstruction Amendments give Congress the power to enforce their terms with “appropriate” legislation. But, like the congressional powers in Section 8, these non-Article I powers do not refer to disputed electoral votes.

Congress cannot use the Necessary and Proper Clause as a bootstrap to invade the powers that belong to the other branches. As the Supreme Court affirmed in the 2015 Zivotofsky case, when an “exclusive” Presidential power is exercised, Congress is disabled from acting upon the subject. The same applies to the exclusive powers of the Vice President. Congress could not regulate, for example, the Vice President’s discretionary power to cast the deciding vote when the Senate is tied.

Pressed to the limit, a state-centric understanding of the electoral vote process could imply that no federal governmental “power” exists at all, whether in the President of the Senate or in any other federal department, to decide vote count disputes. In that case, nothing would exist for Congress to regulate under the “sweeping clause.” This view assumes the process works seamlessly: the electoral votes are transmitted from the state to the President of the Senate; then on a designated day the houses of Congress assemble to watch the President of the Senate open them, count them (or hand them to tellers to be counted), and announce the final tally. The task of the President of the Senate is merely ministerial; she exercises no power of any kind. The sweeping clause is directed to federal powers, not to the execution of ministerial duties—and so, on this theory, it has no purchase. It would appear to follow that the President of the Senate, like Congress, had no role to play in deciding what electoral votes to count. She would have no more discretionary power than a teller would.

But the problem with this radically federalist view is that even when strictly charged with the execution of specific duties like tallying the vote, officials may need to exercise a degree of discretion. State elections officials, charged with counting the popular vote, may have to use good judgment in deciding whether a signature on a mailed-in ballot sufficiently “matches” a signature on file. Something similar seems true here.

The Anglo-American legal tradition has long recognized the need for “discernment” by government agents. Philip Hamburger’s Is Administrative Law Unlawful (2014) cites Chief Justice Edward Coke’s opinion in Rookes Case (1598) to illustrate this approach. Coke wrote that though the commissioners of sewers had discretion in their repair work, they needed to be sure they were properly applying it, and not deciding “according to their wills and private affections.”

The Vice President, when presiding over the electoral vote count, acts as an agent or fiduciary for the states. If the state has properly delivered its votes, her only duties are to open the certificates in the presence of both houses of Congress and to count them or supervise their counting, and then to announce the final tally. Unusual circumstances might arise in which it is unclear what the “will” of the state is. At that point (on the “agency” model), she may properly exercise her judgment in “discerning” the state’s will.

For example, there may be cases where two legitimate state authorities or institutions submit different slates of electors. Assume that each state authority is prima facie qualified to certify the state’s electoral votes. In this case, Harris would need to exercise judgment to discern which slate to count. To do that, she would have to investigate the claims of each authority under state law. She would have to consider any opinions from courts, the state attorney general or state administrative bodies relevant to the appointment of electors. Her duty would be to give effect to the will of the state, not to her own or that of Congress. But she will also be exercising her own discernment and discretion.

This interpretation is compatible with a federalist view of the electoral college. It differs from the more extreme view only by recognizing the reality that a state may not have indicated its will clearly and unambiguously by the time that the electoral votes are counted. In those (narrow) circumstances, the President of the Senate has some interstitial authority.

We thus steer a course between Bessette and Eastman. We agree with Eastman that the President of the Senate has some discretion to resolve electoral vote count disputes— though we do not believe it extends as far as Eastman allows and as Bissette rightly fears it might. We also agree with Eastman that the ECA is unconstitutional insofar as it carves out a role for Congress in dispute resolution or directs the President of the Senate in the exercise of her judgment. But it also requires the President of the Senate to conform to standards of reasonableness and good faith in exercising her discretion to faithfully execute the will of the states.

The Role of the Veep

According to his legal counsel, Pence apparently believed that the Constitution either did not empower him, in any circumstances whatever, to resolve electoral vote count disputes, or else that it affirmatively (if implicitly) barred him from doing so. We believe that the idea Pence rejected was not nearly as unthinkable as he assumed.

Eastman correctly notes that both Vice Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, presiding over electoral vote counts in which they had a personal interest in the outcome, made rulings about disputable votes that favored themselves. And (as Eastman also notes), the prevailing view of constitutional scholars in the early Republic also allowed the President of the Senate some discretionary power (even if those writers also believed that Congress might circumscribe or overrule it).

But even if the idea that the President of the Senate has some discretion is not exactly unthinkable, is it wrong? The fundamental reason Pence gave for thinking so depends on the principle, ultimately derived from Roman law, that no one may be the judge in his own case—nemo judex sui.

This axiom was firmly rooted in Anglo-American common law before the framing of the Constitution, by figures like Chief Justice Sir John Holt in City of London v. Wood. As James Madison observed in Federalist No. 10: “No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause, because his interest would certainly bias his judgment and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity.” Invoking the rule in Calder v. Bull (1798), the early Supreme Court characterized it as among “the first principles of the social compact.”

While this principle is entrenched in our system, is it a constitutional rule? We do not think so. Going by the text of the Constitution, it is not: the text frequently seems to permit self-interested parties to exercise power even where they have a personal interest in the outcome. For example, the President can veto legislation harmful to his financial interests, or pardon himself in any case of federal crime except impeachment. Members of Congress can vote against their own expulsion or set their own salaries. Nothing in the Impeachment Clauses prevents the Vice President from presiding over her own impeachment trial (whereas she is expressly barred from presiding over the President’s trial).

One might argue that our interpretation of the Constitution is too text bound. Former Justice John Paul Stevens argued that the Constitution required the sovereign to govern “impartially.” Accepting Stevens’ position, one might maintain that if Pence had any power to rule on electoral votes (at least in a case in which he was a candidate), he would be acting with partiality towards himself—and therefore unconstitutionally. Stevens’ theory, however, has never been adopted by the Court, and has had no discernible impact on its opinions. Indeed, the Supreme Court has declined to review partisan gerrymandering— surely a paradigm of “partial” decision-making. Moreover, Stevens’ idea proves too much: is every instance in which a constitutional actor decided a question favorably to its personal interest an unconstitutional choice?

It can also be argued that the separation of powers requires multiple decision-makers. As the Supreme Court noted in a 2020 decision, “[a]side from the sole exception of the Presidency, th[e constitutional] structure scrupulously avoids concentrating power in the hands of any single individual.” But the authority we ascribe to the President of the Senate, though it might indeed decide the outcome of a presidential election in exceptional circumstances, is extremely limited. Perhaps it is subject to judicial review. And if Congress concludes that a Vice President has hoisted herself into the Presidency by bad faith, it can impeach and remove her from that office.

2024

How might this play out during the 2024 election? Vice President Harris’ power to resolve electoral disputes would arise, tautologically, only if there are disputes. She does not have a free-ranging commission to challenge or reject votes. If she receives only a single set of certified votes from, say, Pennsylvania, and that certification is provided by a Pennsylvania official with apparent authority to act, such as the governor, she has no role beyond the ministerial.

What happens if she receives two or more sets of certificates, each coming from a state actor with some colorable claim to authority? (Set aside for the moment the case in which the legislature submits one slate and the executive another.) These scenarios could include a set certified by the state governor and another certified by the state attorney general. Or they might be a set certified by an outgoing governor, and a later set certified by that governor’s successor. Or the same governor might send two distinct but incompatible sets. In these circumstances, a genuine “dispute” has arisen, calling for Harris to exercise discernment.

No such scenario occurred in 2021. Here, we think, is the critical flaw in Eastman’s analysis. Eastman’s argument is that a group of individual legislators (but not the legislature as a body) could object to the official certification of electors by their state and present another slate of electors. He further argued that this would create the grounds to ask the Vice President to throw out the state’s certified electoral votes. However, a group of legislators or of self-appointed electors could not plausibly claim to speak for the state.

What if the outcome of the popular vote (and, with it, the appointment of the state’s electors) is still tied up in litigation on the date when the electors’ votes must be counted? If no colorable authority in the state (such as the governor or the legislature) has certified a slate of electors by that date, then there would be no “dispute” for Harris to resolve, because there would be no electoral votes to count. The state would simply lose its electoral votes: it did not speak with a single voice or even with divided voices, because it simply did not speak at all.

Another scenario: what if the state speaks with one voice, but that voice is not backed by the popular vote? Or if the legislature submitted its own slate and the executive branch another? This could occur if the outcome of the state’s popular vote remained in litigation as the day appointed for counting the electoral vote approached, and the state legislature purported to resume its original constitutional authority to appoint electors—but acted unilaterally, without the governor. Here the state would be speaking with a single voice (or two, if the executive submitted an alternative slate.)

The question whether the legislatively designated slate was validly “appointed” is difficult, indeed unprecedented. But the Supreme Court may provide some guidance. The Court has decided to review Moore v. Harper, a redistricting case from North Carolina, which presents the question whether the North Carolina Supreme Court has the authority, consistent with the federal Constitution, to reject a congressional districting map adopted by the state legislature. Although the question arises under the constitutional clause applying to congressional – not presidential – elections, the issues are similar: in both cases, the Constitution vests authority in the state “legislature,” not just the “state.” The Court’s decision in Harper may bear directly on the putative power of a state legislature to appoint presidential electors on its own. Four justices have already indicated that they believe that the legislatures do have at least some power to act independently.

We should all hope that the 2024 electoral vote count is not enmeshed in a constitutional dispute of this magnitude. And other difficult questions could also arise. Even if the Vice President can decide a counting dispute initially, is her decision subject to judicial review? Must she provide a legal opinion in support of her ruling? Can she (with the consent of both houses attending the joint session, perhaps?) adjourn the count and remand the dispute to the state for further clarification? The 2024 election could make the 2020 election seem tame by comparison.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Kamala Harris's staff offer unique insights regarding her leadership skills.

Racism is defined at the discretion of the regime.

The Harris campaign plays the ick card.

The Harris campaign desperately tries to create the appearance of excitement.

Media deception is ongoing.