Rage meets self-pity as the permanently offended root out false thought.

Flawed Prophet

James Burnham and the managerial revolution.

What follows is an excerpt from Daniel J. Mahoney’s essay, “Flawed Prophet,” from the 25th anniversary Fall 2025–Winter 2026 issue of the Claremont Review of Books.

At the time of his death in the summer of 1987, James Burnham was falling into obscurity. Today, though, his work has surged rapidly in prominence on the Right, especially among some of Donald Trump’s most ardent supporters. The reasons for this merit close attention.

At one time, Burnham was widely known as one of America’s sharpest Marxist intellectuals. His most recent biographer, intellectual historian David T. Byrne, ably captures the young Burnham’s contradictions in James Burnham: An Intellectual Biography: a professor of philosophy at New York University, unapologetically bourgeois and completely in his element at black-tie dinner parties, he could respectfully engage Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. Yet he was also a militant Marxist and a trusted protégé of Leon Trotsky, whom he met and befriended in the 1930s. Distraught over the mass unemployment that was then sweeping across the United States, he admired the ferocious determination of the Marxist revolutionaries who promised an overthrow of America’s supposedly irredeemable capitalist system. Byrne writes that he “loved the idea of violent revolution.”

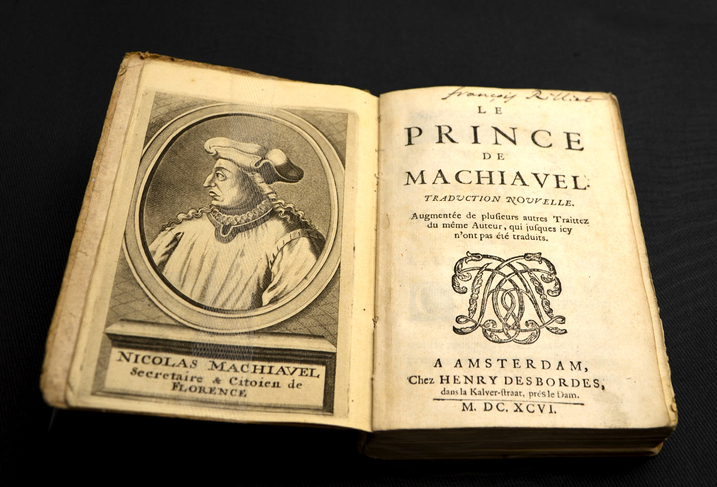

Yet Burnham was too intelligent and humane to remain impressed with the Soviets for very long. In 1940, his life took a decisive turn when he broke with Marxist-Leninism. Trotsky and his acolytes denounced him as a nefarious traitor. But Burnham would go on to compose what Byrne correctly identifies as “two of the most successful political works of the 1940s”: The Managerial Revolution (1941) and The Machiavellians (1943). He became a public intellectual, appearing regularly in journals of the Left-liberal New York intelligentsia such as the Partisan Review. He was even recommended by George Kennan to help with anti-Communist efforts at the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA.

That was a harbinger of more changes to come. Having once defected from the Marxist vanguard, he eventually became persona non grata among New York’s liberals, too. They could not abide his adamant opposition to Communism or his refusal to see McCarthyism as an unequivocal evil. So he found himself politically homeless yet again, until he helped William F. Buckley, Jr. found National Review in the fall of 1955. He would write hundreds of columns and articles for the magazine and its offshoot, the National Review Bulletin, until his short-term memory was impaired by a stroke in 1978.

Though he was forced to wander from tribe to tribe, his own point of view remained fairly consistent. He thought of himself, not as a partisan of any particular ideology, but as an uncompromising realist committed to hard-nosed assessment of life as it was, not as it should be. His writing was marked by what longtime National Review senior editor Jeffrey Hart described as “stoic detachment.” His constant concern while at the magazine was to avoid undue polemics and make an even-keeled argument that conservatives could be capable of governing in a responsible manner.

His conservatism was layered, and it came on him gradually. But it was indisputably principled and sincere. Byrne writes that “the young Burnham was a Marxist who believed revolution could regenerate the world. The middle-age Burnham was a Machiavellian who believed that the ruling classes must be resisted for tyranny to be thwarted. The most mature Burnham embraced Burke.” His most satisfying and compelling book, 1964’s Suicide of the West, is also his most conservative. Hart once speculated that if it had been published in 1987, when the full ravages of untrammeled liberalism had become more apparent, it might have been a bestseller along the lines of Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind.

Suicide of the West was republished in 2014 in a handsome edition by Encounter Books, with thoughtful introductory reflections by John O’Sullivan and an overview by Roger Kimball. The Managerial Revolution and The Machiavellians are also freshly available in inexpensive paperback editions. And Byrne’s biography was preceded in 2002 by Daniel Kelly’s lengthier and even more sympathetic James Burnham and the Struggle for the World. Today, conservatives of diverse varieties invoke Burnham to critique the “soft managerialism” that has grown ever more heavy-handed and unaccountable in its domination of public and private life.

Of Managers and Machiavels

The Managerial Revolution, Burnham’s first book after his break with revolutionary socialism, is destined to remain a significant if imperfect piece of work. Its provocative thesis stirred controversy immediately upon publication. The socialists were right that capitalism would soon be obsolete, Burnham argued, but wrong that socialism would take its place. Instead, “managerialism,” the rule of managers and experts who did not need to own property, would define the regimes of the future.

In a 1943 essay “On Historical Pessimism,” the French political thinker Raymond Aron criticized The Managerial Revolution for its dark fatalism and its spurious prediction that Nazi imperium, however modified, would survive the war. Aron, who later became close to Burnham, believed he had been far too quick to proclaim that the bourgeois liberal order was doomed. As Byrne points out, writers such as Friedrich Hayek in The Road to Serfdom (1944), Peter Drucker in The Future of Industrial Man (1942), and Ludwig von Mises in Bureaucracy (1944) were able to accept much of Burnham’s empirical analysis while still mounting powerful defenses of liberal values and the market economy.

Others noted that Burnham was still too indebted to the Marxism he was leaving behind: in characterizing Soviet rule as a particularly despotic form of managerialism (rather than full-blown ideological totalitarianism), Burnham was ultimately echoing Leon Trotsky. Still, George Orwell praised Burnham for his “intellectual courage” and for writing “about real issues.” The “forbidden book” in Orwell’s 1984, Emmanuel Goldstein’s The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, is self-consciously modeled on The Managerial Revolution. The staying power of the work shows itself in its continued presence as a point of reference in the literature on bureaucracy and the administrative state.

Read the rest here.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Conserve your spine or lose it all.

Or, How to (Posthumously) Conquer the World from Your Desk

The incompatibility of the NDAA and the National Security Strategy.

One dose will erase your whole political mind.

Our dark hour calls for a recovery of the statesman’s virtues.